I delivered the following address (slightly edited) at the Aberdeen, SD American Legion Memorial Day exercises on May 25, 2020.

Aberdeen, SD. Memorial Day, as the name suggests, is a time for remembering. In the United Kingdom they call what we honor as Veterans Day, which used to be Armistice Day, Remembrance Day, remembering the end of the First World War. It was long a tradition that as part of Remembrance Day events Rudyard Kipling’s poem “Recessional” would be recited. This poem repeats two lines throughout: “Lord God of Hosts, be with us yet, / Lest we forget—lest we forget!”

A people that forgets is in some ways, Kipling suggests, committing a sacrilege. Part of what a healthy culture does is memorialize those who went before and who made possible the goods we are blessed with today. Take a fictional example. J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings contains sixty songs or poems sung or recited by various characters that often help bring meaning to the characters’ own adventures. Whether it is Aragorn reciting part of the “Lay of Lúthien and Beren” on Weathertop Hill, the story of Eärendil told in Rivendell as the travelers take a rest, or Legolas singing of the tragedy of Nimrodel as the Fellowship prepares to enter Lothlórien, the people of Tolkien’s fictional Middle-earth use verse as a kind of history. The history of Middle-earth is not captured in works that simply record what happened, but instead in poetry that turns past events into meaningful stories.

Statesmanship at its best contributes to this memorializing of the past and those who sacrificed so much for our good. America has never produced a greater statesman than Abraham Lincoln. One of the things that makes Lincoln remarkable is precisely his ability to turn political teachings into a kind of poetry. I don’t think this is an accident. Lincoln, I would say, was not a man who read widely, but he read deeply. There are sources that Lincoln read with care and returned to repeatedly. Despite having what we might call unconventional religious beliefs himself, Lincoln devoured the Bible. Of course in Lincoln’s day the King James Bible, the most poetic of translations, was standard, and for Lincoln its language was second nature. His speeches are filled with biblical allusions. Lincoln also had mastered various works of Shakespeare. He returned again and again to certain plays: Macbeth, Richard III, Hamlet, and Julius Caesar being among them. Lincoln could quote entire scenes of Shakespeare from memory. These two influences gave Lincoln the language to take complex and controversial ideas and deliver them to an audience in a way that would appeal to both the head and the heart. One of the arts of statesmanship is the use of language, of rhetoric, to reshape the architecture of people’s souls and orient them towards political truths.

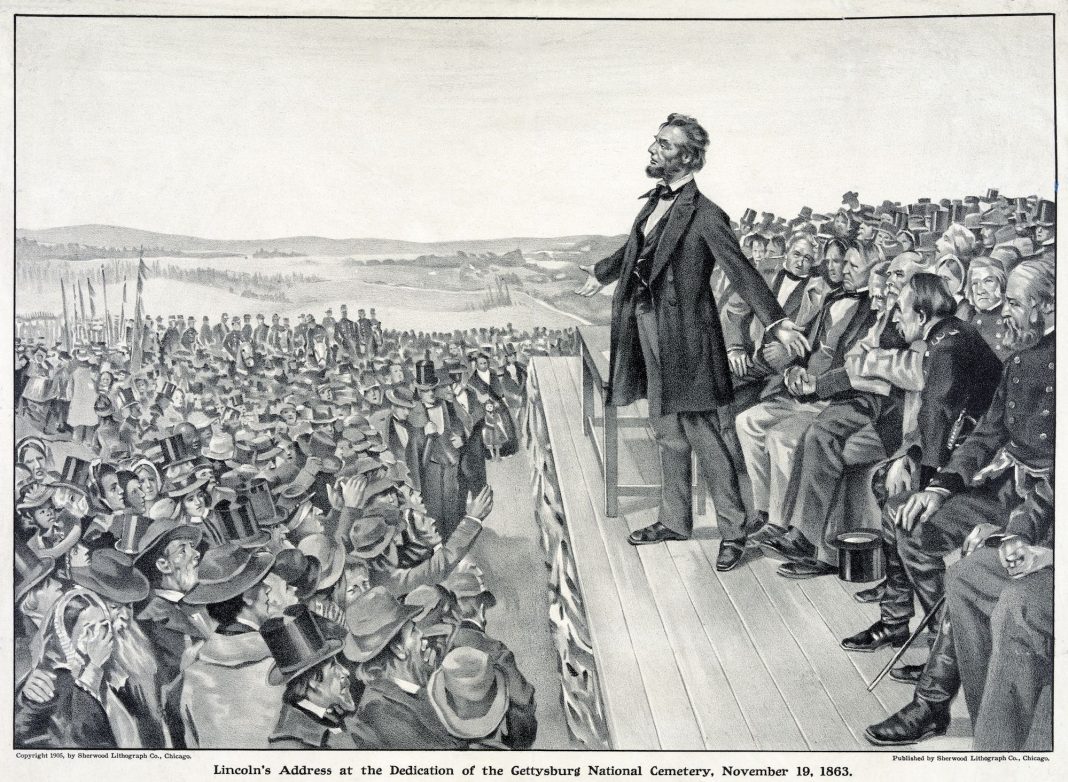

Lincoln combines poetry and the concept of memory in his most famous speech, the Gettysburg Address. The very structure of the address directs our attention to the past, the present, and the future. The Gettysburg Address works within what in some circles is called a “hermeneutic of continuity.” This is a fancy way of saying we should apply timeless truths to new situations. Change is possible, but it is not the result of mere innovation. All change must occur respecting certain foundational doctrines that precede and serve as limits to innovation. Richard Brookhiser, in a work that explicitly ties Lincoln to the American Founding, writes, “Lincoln’s most important allies in these efforts were the founding fathers. They were dead…. But Lincoln called them back to life for his purposes. Their principles, he maintained were his; his solutions were theirs. He summoned the past to save the present.” So as a Christian might view scripture and the early Church as the source of continuity, Lincoln viewed the American founding. All change should be in continuity with fundamental principles.

The Address starts with a call to remember. The famous first line, “Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” This calls us to remember something that happened in the past. Of course the math takes us back to 1776, calling to mind the Declaration of Independence. For Lincoln the Declaration is a kind of deposit of faith that we must hold onto and retain. Lincoln appeals to the past: As Glenn Thurow has written, “The authority of the past does not prevent reform. On the contrary, it allows reform because an appeal to the past allows the good to be preserved while exorcising the evil.”

Lincoln then moves to the present. “Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure.” What question derives from the presence of civil war in the US? It is, “Can any nation conceived in liberty last?” Is democracy even possible? Can this nation endure? These men died so that it can. He says, “We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live.”

Lincoln then moves to the future. He says that we have unfinished work to do as a nation. What is this work? To make democratic government and equality a reality. That democracy shall not die, “shall not perish from the earth.” If we give up the principles of the Declaration, if we give in to the arguments of the Confederacy for example, we are dishonoring the dead. We will have forgotten what they died for. There is an explicit call to remembrance when he says, “The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here; while it can never forget what they did here.” So he calls on his listeners, and us, to be dedicated to this cause of the Declaration, so that the dead shall not have died in vain.

Thurow once wrote of the Gettysburg Address: “To the question, Is democracy good?, common opinion answers, Yes, because the people are wise and just. Lincoln, too, in the moment when American democracy was put to its greatest test, thought democracy to be finally good only if the people are wise and just…If the people are not ultimately just, then there is no reason other than expediency why they should decide questions of justice.” Lincoln needs to take the truths that the Declaration says are self-evident and teach them. So they aren’t self-evident, but what Lincoln calls “propositions.” They are proposed to us, and we must decide whether to accept them or not. If opinion in favor of these propositions starts to slip, then the statesman must redirect attention to the founding and its enduring meaning.

This is what Memorial Day is for. Not just for those who died at Gettysburg, but for us to remember all who have died in service of a country dedicated to noble ideals. It is for us, the living, to use ceremonies such as this, and also schooling, art, poetry, and statesmanship to call people to remember that sacrifice and what it was for. What are the founding principles of the nation? Why are they good? If we remain dedicated to this task of active memory, then our honored dead surely will not have died in vain.

A problem I have in this context is not to take issue with the frequently amazing generous bravery of soldiers and sailors. It is that I remain aware that many, very many were blunderingly wasted or swapped for greater wealth for the wealthy.

Comments are closed.