1. Houellebecq Contra Mundum

Washington, DC. Something is rotten in the contemporary novel; something is sleepy and effete. Between, on the one hand, the peculiar struggles of those of us who live in the “developed world” and, on the other, their treatment in new novels, a strange and as yet unarticulated gap has opened up, as though a photographer were struggling to render a colorful scene using only black-and-white film. Not the absence of the particulars of our social life, not an essentially journalistic or documentary failure, this artistic paucity seems to reach into the very marrow of the novel form, as though some Lamarckian urge to evolve were stirring painfully within an already antiquated organism.

I make an exception for, among others, Michel Houellebecq, whose books have the distinction of being not only read but voluntarily discussed in public by people not conspicuously on the take. To understand how outstanding this feature is, one only needs experience with book chat at some gathering “IRL,” where novelistic criticism has been reduced to a mild, even vaguely ashamed recommendation, followed by some lackluster assurance that reading the novel wouldn’t be a total waste of time. The spectacle of Nekrasov bursting into Dostoevsky’s apartment in the wee small hours of the morning to congratulate him on his writing Poor Folk now seems about as likely as a janitor earning a ticker-tape parade. In short, the working novelist today has been demoted to the status of a craftsman of imitation antiques, and we no longer go to fiction to understand where we are and why.

But again, singularly, inescapably—Houellebecq. Just what is so Houellebecqian about him, what gives him his peculiar briskness? Is it his openness to the scatological, to the violent, the racist, the sexist, and all the other delights that we see plainly inscribed every day on that largest and most widely read publisher of today, the Internet? No, the twentieth century was largely the history of novelists shattering the bounds laid down by their great bugbear, the Victorians. Those idols of propriety lay smashed to dust long before Houellebecq was born. The meaning of Houellebecq hoves into view only when we examine his work in light of broader cultural history. Admirable essays on his work (for literary insight as well as biographical data, I refer readers particularly to essays by Mark Lilla, Anthony Daniels, and John Banville) have nevertheless passed over the truly distinctive features of his novelistic skill.

The art of storytelling is for the most part the art of choosing what to leave in and what to leave out, and what Houellebecq leaves in is what many writers have chosen, or been induced, to leave out. These inclusions aren’t his inventions. They swarm us now, beleaguer us, pen us in. They are the products of a world suffused with technology, and of the attendant detachability of human relations. They condition the warp and woof of our social fabric. And his frank portrayal of them is what gives the sense that Houellebecq, preeminently, shows us the world as it is.

Call these depictions, first, the “sociological soliloquy,” and, second, the “sought cliché.” Each is a fresh and intransigent form of human unfreedom, and Houellebecq has exhibited them to us with disturbing precision.

2. The Sociological Soliloquy

A novel of ideas in its vulgar form is the dramatic illustration of an already rigid conceptual schema. It would be an insult to the riches of medieval allegory to compare contemporary specimens to that genre. The better analogue by far would be Highlights for Children’s Goofus and Gallant cartoons: Gallant abides by the strictures of the ideological law code and Goofus does not. Goofus is, if not punished, then condemned in blazing neon lights so that even the most birdbrained Goodreads contributor can recognize his perfidy and feel morally sated for a few minutes. But, at any rate, more important than the stale events related in the text is the very soothing idea that the righteous ideology remains as stable as the national currency, that all social problems have a lucid explanation, and that, if we find ourselves confused and unhappy in the modern world, we can look up the answers, just as we could flip to the back of the math teacher’s textbook, where all the solutions to all the problems are printed in indelible ink. These works give a cheap, corn-syrup pleasure when your sect is in the saddle, and their faults gain visibility only when your enemy’s ideology gains the whip hand. Much or most pretentious television also fits this description. Certain material conditions have lately made this rigid Goofus and Gallant genre ascendant: most “working writers” today in fact earn their living from hierarchical organizations, and the worldly-wise among them will quickly learn how to signal their devotion to their employer’s ideology, so as not to be thrown into the breadline.

So much for the common run. The other, superior way to write a novel of ideas is to depict characters who by their nature have dealings with ideas, just as they have dealings with bridges, siblings, sickness, and the supermarket—which is to say these characters have ideas, rather than only serving as their mechanical illustrations. Like flesh-and-blood human beings, these characters will use ideas as tools, totems, consolations, or katanas. Stimulated and stricken by the concepts floating through their culture, these characters have an intellectual point of view, just as any living human being has a precise shape to his nose. To set such a novel in an intellectual milieu, such as a revolutionary cell or a coven of professors, is a clear and reputable path. Still more pertinent to our times is the genre not precisely invented but brought to a fresh pitch of intensity by Houellebecq: the novel of ideas in which the characters philosophize simply to make sense of their bewildering surroundings. There, ideas are no longer passions but a makeshift means of psychological survival, a pup tent in a snowstorm. These thinkers don’t volunteer for the illustrious life of the mind; no, life impresses them into mental service. Pointing klieg-lights at this subtle but all-important change in the human relation to ideas is what accounts for Houellebecq’s success in resuscitating the novel form, that revered elderly person whose death is continually being announced.

The character who engages in a sociological soliloquy is perhaps Houellebecq’s key narrative innovation, and it is as essential to his art, as, say the wild vista was to Wordworth’s. But how different it is from the interior conversations conducted in Shakespeare or in the masterworks of the nineteenth century. Let the following passage serve as a representative sample of Houellecbq’s sociological soliloquy. François, the Parisian protagonist and narrator of Submission, tries to make sense of his pain as a series of girlfriends leave him:

The way things were supposed to work (and I have no reason to think much has changed), young people, after a brief period of sexual vagabondage in their very early teens, were expected to settle down in exclusive, strictly monogamous relationships involving activities (outings, weekends, holidays) that were not only sexual, but social. At the same time, there was nothing final about these relationships. Instead they were thought of as apprenticeships—in a sense, as internships…

Such a model, he reflects, supposes that after ten to twenty such “internships,” a lasting monogamy will take hold, followed by the famous “family formation” that we hear mentioned in the academic literature. And yet for François, even as he approaches middle age, no such fecund terminus is in sight, for the simple reason that all his girlfriends break up with him. Life has thrown François into a labyrinthine game that he neither designed nor assented to play. Life, of course, did the same to his ancestors. But weigh the difference: François is the first to play the game in its current form, and he has no reliable proverbs to guide him—and no second chance. He has no reason to suppose that the current social labyrinth enfolding him will remain static for long. When the rules are always changing, nobody wins the game except by luck. Social mores once drifted like continents; now they shift like sandbars. And if François wishes to understand his inability to sustain a romantic relationship, the wisdom of the ages is no help. François must theorize—not because he is curious, but because is miserable. Kant said reading Hume roused him from his dogmatic slumber. François’s journey is less like naptime interrupted than a series of regular beatings, administered not by books but by daily social intercourse. Here is a new species of thinker.

It may be said that Houellebecq is no pioneer because novelists down the centuries have registered changes in social mores with the sensitivity of a seismograph. (“If you ask me, sir, it’s all on account of the war. It couldn’t have happened but for that,” says an Oxford “scout” in Brideshead Revisited, protesting vigorously the introduction of dancing to a regatta celebration in 1923.) But when changes become sufficiently numerous and rapid, their quality alters. When everything around you writhes, no longer do distinct changes pop out from a stable background to serve as subjects of careful inspection. A technological society is by necessity a mobile one, where the high-octane speed of social change is so staggering that it gives the notional etiquette book the shelf-life of about a month. Quantity, as Stalin noted, has a quality all of its own.

Human beings now find themselves forced to concoct handy social theories—not out of curiosity, but out of need—because we live in the aftermath of a tremendous explosion. We need to acquaint ourselves with the building that now lies in ruins around us. The name of the building is human culture. In his Secret of Our Success (many thanks to Scott Alexander for first bringing this book to my attention), Joseph Henrich propounds a theory of cultural evolution at once simple and far-reaching: “Much of our seeming intelligence actually comes not from raw brainpower or a plethora of instincts, but rather from the accumulated repertoire of mental tools (e.g., integers), skills (differentiating right from left), concepts (fly wheels), and categories (basic color terms) that we inherit culturally from earlier generations.” In short, “[w]e don’t have these tools, concepts, skills, and heuristics because our species is smart; we are smart because we have culturally evolved a vast repertoire of tools, concepts, skills, and heuristics.” One study cited by Henrich suggests surprisingly that young children exceed great apes in social learning, but not in “space, quantities, or causality.” Imitation and inheritance, skill and habit, are the significant human potencies, compared to which analysis shorn of context, and now lionized as “IQ,” is comparatively feeble.

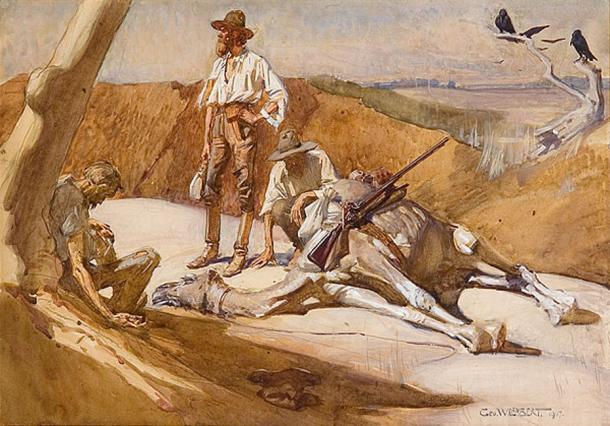

If this seems preposterous to denizens of countries where test-taking is for now the royal road to bourgeois comfort, consider a story Henrich relates for illustration. In 1845, Sir John Franklin led a British expedition in search of the Northwest Passage. Though eventually locked into the winter ice some 600 miles north of the Arctic Circle, the ice-breaking ships under Franklin’s command were stocked with desalinators, canned food, a twelve-hundred-volume scientific library, and other signs and wonders leaving no doubt that this mission represented the cutting edge of European technological magnificence. That the whole crew gradually died, and only after resorting to cannibalism, is not so shocking as the fact that in the same harsh environment human beings have lived for over 30,000 years without the help of desalination, canning, or even the written word. These Inuit locals even found remnants of the crew and gave them seal fat out of pity. But, as Henrich notes, “individual intelligence” had nothing to do with Inuit success or British failure in the Arctic Circle. Rather, the Inuit inherited a “vast body of cultural know-how,” a set of skillful practices knit together like the tissues of an organism and grown over millennia. Seal-hunting alone needs knowledge of where and how to find seals’ breathing holes in the ice, how the holes smell when seals are present, how to assemble a harpoon from caribou antler and polar bear bone (both are essential), how to build a driftwood bow to kill the caribou needed for the harpoon, and so on. Cooking the seal, too, needs specific skills not only unguessable but seemingly unlearnable without a deep culture at your back. No individual, no matter how rich in IQ, could contrive these intertwining skills while stumbling across the frozen deep. The Inuit that Franklin met neither invented nor intellectually defended these practices; rather, they inherited them and daily employed them.

Henrich presents another instructive story of European explorers dying in agony. Robert Burke and Williams Wills lead an expedition into the Australian interior. By the winter of 1860, they had exhausted their supplies, eaten their pack animals, and were attempting to live off the land. After devouring a gift of “bush bread” from local aborigines, the Yandruwandrha, they learned that these cakes were made from nardoo, a seed-like “sporocarp” from a fern. They then began to live entirely on nardoo “bush bread” that they cooked themselves—but, despite eating sufficient calories, they became weak and immobile. Harried by painful diarrhea, they all died save one. Little did they know that the aborigines obeyed several rules in the course of making their cakes: grinding and leaching the flour with water, exposing the flour to ash during heating, and eating the product only with mussel shells. Modern science came to justify these practices as inhibitive of the effects of thiaminase, found plentifully in nardoo and tending to deplete the body of Vitamin B1. But the Yandruwandrha knew nothing about thiaminase and had no need to. They ate with mussel shells because it was comme il faut and this “incurious conformity” kept them alive for thousands of years.

Does any of this by chance remind you of anything? The image of eminently intelligent Europeans stuffing their bellies with nardoo in the outback, but starving to death in total confusion as to how their glutted selves could nevertheless be dying miserably of hunger—does that maybe ring an analogical bell? In the literal stories of the Old Testament, certain fathers of the church often detected a less obvious and yet highly significant spiritual meaning. I would suggest that stories of people plucked from their natal cultures, and soon starving to death under foreign constellations, should now be read figuratively, as an awful prefiguration of the psychological torments of those who live in a technological society—well fed, engulfed by air conditioning, but dying inwardly of despair. What else do we glimpse on the Internet, abounding as it is with advice and pleas for advice on how to make a living, how to find a mate, and how, in your dwindling spare time, to discover what life might mean? Or the voluminous op-eds, nominally “social criticism,” and yet so obviously a sublimation of these same message-board howls of the damned? The sheer volume of this “content” suggests the absence of an answer.

I paraphrase Henrich’s work to suggest that what applies to physical survival applies as well to spiritual flourishing. The Yandruwandrha did not justify their gustatory customs by the common consent of individuals who had engaged in a thorough and unprejudiced analysis of their surroundings (the Enlightenment vision of model governance). Nor did they form hierarchical institutions to correlate scientific first principles, from which they would then derive an unimpeachable Food Pyramid to supplant the habits of the many. Rather, the Yandruwandrha constantly prejudged their world in light of inherited patterns. The trials of the ancientry served as their science, and a much more reliable one it was than much of our social science, to say nothing of our Food Pyramid. And yet to call traditional customs “rules” would be to retroject our modern sense of law and technology consisting of clear-cut mechanisms. Traditional customs seem more like a brackish mixture of the conscious and the unconscious, analogous to how I’m both conscious and unconscious of what my fingers do as I slice an onion. Just as many can speak grammatically but would struggle to list the rules of grammar, traditional people could obey principles without articulating them, beyond semi-poetical proverbs and rules of thumb. In a “developed” society, however, all choices become hideously explicit. The individual no longer acts according to acculturated habits and skills but only according to rules. And the atomized individual must legislate his own rules of conduct or become paralyzed. How to get a job in this economy? How to find a mate, or, barring that, a roll in the hay? How to bring up children? How to acquire the good opinion of others? The wisdom of the dead no longer supplies reliable answers. Even if I attempt to resurrect some traditional practice, I do so by adopting it as an explicit rule (“avoid seed oils”; “avoid blue light after dusk”), and not as a custom enfolded into my culture.

And so we return to Houellebecq. In his work, human beings, bereft of their traditions, which they could not have invented, find themselves in much the same hideous position as those European explorers—starving to death, spiritually, and yet unable to do anything about it, not because they lack intelligence, but because no single person or even any single generation is smart enough to engineer reliable rules of social conduct. The Yandruwandrha cooking customs secured survival. But the human being is that peculiar organism not content with survival: presented with an existence consisting only of survival, that organism will prefer death, often in slow motion. The customs securing our spiritual flourishing are if anything even subtler and less justifiable to reason than those governing the preparation of bush cake. Those cretinously repeated calls for individuals to “make their own meaning” no longer seem like a beckoning to Valhalla so much as a train ticket to Ukraine, circa 1933.

Though Houellebecq began publishing in the early 1990s, his novelistic innovations were well suited to surviving the internet’s ongoing Mongol demolition of literary culture. A striking feature of the past few decades is how much of the oxygen that once fed literature has been slurped up by “online.” The vapid artificial gossip of bad novels yielded place to the vapid documentary gossip of social media. Satire especially seems superfluous now, given the bizarre outrages immediately available in every smartphone. If Houellebecq seems an exception to this not altogether heinous extinction event, it’s perhaps because he depicts people who no longer shore up their besieged psychologies through art, religion, or tradition but through the panicked sociology of a spiritual drowning victim. Although, in The Map and the Territory, he depicts a fictionalized version of himself who prefers reading cultural tracts by the likes of Proudhon and Carlyle instead of novels, it remains that he writes novels about people reading cultural tracts and not tracts themselves. Houellebecq isn’t a sociologist so much as a painter of people forced to engage in sociology of a peculiarly solitary and desperate variety. “It’s strange, I’m fifty years old and I still haven’t made up my mind whether sex is good or not,” he told a journalist. “I have my doubts about money too. So it’s odd that I’m considered an ideological writer.” The source of the confusion is simply that most critics assume a novel of ideas must be written in the sainted tradition of Goofus and Gallant.

Everywhere in Houellebecq we meet characters pinioned by immense social mechanisms they barely understand. In one recent novel, French stockbreeders watch helplessly as the EU’s elimination of milk quotas thrusts them into bankruptcy. The protagonist’s stockbreeder friend, the last of an aristocratic line, dies spectacularly in a suicide by cop and remarks as is he driven up against the economic wall that “the more I try to do things correctly, the harder it gets to make ends meet.” The protagonist himself had earlier written agronomic reports against this very deregulation, but they made no difference: his superiors always ignored his proposals. Tocqueville’s “network of small, complicated, minute, and uniform rules” now stretches across the globe, as it must when commerce stretches similarly wide. The result is the abolishment of all significant self-reliance: “My technical competence falls far short of Neanderthal man,” remarks another character, “I’m completely dependent on my society, but I play no useful role in it.” The last sphere of autonomy is the innermost mind, where the characters are “free” to speak their sociological soliloquies, a lonely task. In The Elementary Particles, when a character has a gratifying conversation with his new lover about the deleterious effects of feminism, it rings false, seeming like a hallucination. In his recent novels, Houellebecq is more just. The social criticism is now hideously private, as it must be.

In Houellebecq, the solitary person seems to live his life facing an enormous screen where public events flash and vanish. The screen offers judgment and instruction but doesn’t exactly see the individual being judged. The only other sources of judgment are the transient sexual and employment relations into which the individual enters with a certain ironic distance, conscious that these bonds are dissolvable at will. Contrast the technique in Dostoevsky’s Demons, where a narrator surveys the characters from the perspective of the proper people of the town. When Stavrogin pulls the nose of a respected club member, the “we” scandalized by this action is truly a living gaze, and, though a literary device, this chorus has roots in real human relation and real human investment. Though a “novel of ideas,” Demons depicts a milieu where ideas must still play on the instrument of enduring human relations to turn audible. Not so in Houellebecq. There the radio waves of ideological ferment stream directly into the privacy one’s skull. The judge of human action is somehow no longer human.

Another contrast. Rubashov, in Arthur Koestler’s novel Darkness at Noon, reckoned with the painful intricacies of Marxism-Leninism that had brought him to his prison cell in Stalin’s Moscow. In a sense, a society like ours, committed as it is to the unnegotiable detachability of every human being from any other (a condition euphemized as “freedom”), forces every person to become a Rubashov, except the intellectual effort needed is even harder. Marxism-Leninism is, to paraphrase Walter Sobchak, at least an ethos; the jumble of moralities now surrounding the individual gives no purchase. A scientist can abstract laws from a regular phenomenon; but when the regularities themselves shift, he becomes helpless.

This Bosch painting prompts the old Russian question: what is to be done? Certain rightists lacking in experience, discernment, or both will prescribe a return to old rules. Full of good intentions, some social conservatives have urged their readers to revert on their own initiative to vanished modes of propriety, dress, courtship, and business. But this is tantamount to advising the arctic explorers to behave as though they were still in London. We have exited the habitat that sustained old customs. Tradition is, or was, reliable because it was put to the test in a somewhat stable environment, where the heirs to the tradition still lived. Tradition was never advantageous simply because it was handed down; it was advantageous and it was handed down because it was tried and true. Yet this needs qualification. Strangely, unless the heirs received the rules with a credulous reverence, indifferent to being convinced that the rules were effective, such rules were unlikely to escape a Darwinian culling, since their import was rarely obvious: by the time I’m convinced that that unleached nardoo causes starvation, I’m already starving. A seemingly baseless piety and not a devotion to efficacy was what made traditional people effective. But to maintain this piety in our erratic and technological surroundings is to betray misunderstanding of what made the traditions originally valuable: their womb-like context. When I obey obsolete rules, it’s as though I were trying to work a vacuum cleaner without an electrical source, running it over rugs and feeling confused by how little dust it draws in. Much rightist thought now resembles doting over a collection of defunct vacuum cleaners because once upon a time they could keep a house clean. Unpracticed traditions turn effete, and, in the relay race of culture, one sloppy generation disinherits all descendants. Knowing how to cook nardoo is beneficial so long as I live off it, and, in the measure that I don’t, other concerns preoccupy me, and all nardoo knowledge vanishes. But this is no guarantee that, for example, the foods I eat under the reign of technology are really salutary: these new patterns were engineered within decades and not grown over generations. That traditions turn decrepit in a technological society is no guarantee that their hastily-built replacements will help me live or flourish. The slogans about modernity—“we can’t go back,” “it’s too late”—are true but not consoling.

As Nietzsche knew, the consequences of changing metaphysical attitudes take even longer to become manifest than the consequences of physical changes. When technology takes a person away from farm and garden, it can supply canned foods and microwavable meals, because these can be engineered. But when technology razes prayer and fasting, no engineer can replace them, because the spirit can’t be gripped or hewn, melted down or mass-produced. The internet’s teary, wrathful, and failed attempts to engineer meaning in the wake of cultural collapse are only the first fruits of what centuries to come will make plain.

But the individual is still faced with living his life. Yet when the rules are constantly shifting, how can he plan it? When the climate changes day to day, what clothes should he buy with limited funds? Any human project needs time for its realization, and the nobler the project, the more time is needed. Every human culture experiences shocks and tumult. But it’s precisely because of a baseline of stability that these shocks are registered as shocks. Ours is the first society dedicated to perpetual tumult for its own sake. I can hack a rock with difficulty; I can never sculpt a stream. Is it any wonder that, thrown back on our own resources, we find ourselves crafting social theories both elaborate and crude as a means of getting a grip on our ungrippable surroundings? Our ancestors didn’t survive or flourish by becoming cultural theorists of this kind because the solitary human mind is simply too weak to make meaning from scratch.

We arrive at this strange paradox: the more visibly dynamic a society is, the less spiritual freedom any individual can evince in it. The more freedom afforded to the individual in the short term, the less freedom afforded to him in the long term, if we correctly understand freedom as the ability to realize our highest values. I can, with an ease granted none of my ancestors, detach myself from my native situation, and make choices culinary, sexual, spiritual, and sartorial which I don’t have to justify to anyone. Even if others find my choices immoral, they can do little to stop me, not only because it would be impractical but more deeply because of an ideological undertow biasing me to feel that any choice made in apparently sound mind and without evident duress must be unassailable. But my mobility is only possible because the parts of my world are themselves detachable and slide over and away from each other like grains of sand. Some might call that price too dear.

One last point before leaving this subject. It will be said that tradition was a source of enormous unhappiness to those who lived under its strictures without ever having chosen to. True enough, and no reader of Chekhov, Naipaul, or Agatha Christie can deny it. But what makes you unhappy may also be what keeps you from suicide, just as an itchy and suffocating mask nevertheless guards your lungs from evil particles. The mask was itchy, and we took it off.

3. The Sought Cliché

Cliché—critics have issued a warrant for Houellebecq’s arrest on this supposed literary felony. And, true, his novels are full of schizoid sex addicts, lonesome corporate spinsters, randy New Age gurus, and vapid office workers on even more vapid vacations—the parade is steady and repetitive, and beyond illustrating five or so types his characters are scarcely distinguishable. “[E]xperience has quickly taught me,” remarks one of his narrators, “that I’m only called on to meet people who, if not exactly alike, are at least quite similar in their manners, their opinions, their tastes, their general way of approaching life.” Cliché, then, is not only Houellebecq’s technique but his subject. Yet from our treasury of received ideas we know that cliché is what the novelist should avoid on pain of death.

But the nature of cliché has been much misunderstood since literature fell into the clutches of the academic-critical complex. Aping the sciences, they made an idol of novelty, when really any work of art must take its departure from inherited patterns. No scene, no character, can be both intelligible and totally unique. The truly unique is invisible to the human mind because, as Nicholas of Cusa tells us, all knowledge is in the nature of a comparison. Most thought is crude categorization. Moving through the hassles of the day, we meet people and slot them more or less immediately into prefabricated categories: the employer, the employee, my creditor, my debtor, the one who annoys me, the one standing in my way. Because at any moment I can attend to only a few aspects of reality, I will tend to attend to whatever is most immediately useful to me. I can flatter my judgment by imagining that I see deeply into things when I recognize that the woman I’m negotiating a business deal with is also someone’s daughter, a Mormon, and an accomplished skier. But this only avails me again of the limited dropdown menu of cliché. I only smashed together three or four stereotypes like globs of clay—in no way did I escape stereotype as such. In practical life, then, every human being must treat the rest of humanity as a bad novelist treats his characters.

Compare my practically-minded perceptions of others to my immediate experience of myself: employee, supervisor, taxpayer, mortgagor, and the subject of records both written and transmitted through the jungle drums of gossip… in my depths, I in no way agree that these descriptions exhaust me. For every quality I evince, I find an equal but opposite quality hidden within myself. The brash person enfolds a secret shyness; the libertine obscures an ascetical something. “You would play upon me; you would seem to know my stops; you would pluck out the heart of my mystery . . .” What Hamlet shouted could be shouted with justice by anyone. With respect to myself, I find this merciless categorization unacceptable; with respect to you, expedient, if mildly regrettable. Contradiction, and not consistency, is the hallmark of first-person experience. This is the main theme of Montaigne’s essays.

Fine, then: ostensibly a novelist who aims to paint humanity as it is should paint, above all, the jarring contradictions enclosed by the individual soul. But the necessities inherent to drama prevent the limning of an entirely contradictory nature. Drama is the visible playing out of human habits and desires, and a moving and memorable scene will often depict desire turned awry. The plainer the desire, the more repetitious the habit, the more legible the scene will be to the viewer, given the limits of the human intellect. But a just scene is one in which the characters’ desires are done justice, and any scene that brings forth the human being as a welter of clashing desires will make us feel that we see a real human being. A legible scene is one in which the habits and desires of the characters are less expansive than what we find most immediately in ourselves. The storyteller is pulled in two directions. A character with a single, plain desire can be at best an extremely legible action hero (defuse the bomb! save the girl!) The singleness of the action hero’s commitment provides the pleasure of the genre, which is an escape from our reality. Unlike his, our desires are plural, cacophonous, and undulant in their intensity. Our habits vary in varying contexts. The real, paradoxical human being squirms and frisks too much to serve dependably in the dramatic mechanism. Fine features must be drawn in thick marker. To present the contradictory human being within a legible drama takes the genius of, say, a Shakespeare.

The notion that an author has to offer a catalogue of background details and life incidents to make his characters “round” breaks continually on the reef of Shakespeare’s achievement. What memoirs the plays enfold—Cassius recalling how he saved Caesar from drowning, for example—are nevertheless integral to the present-tense drama. Compared to certain characters in the great novels, we would find it impossible to write any satisfactory cradle-to-grave biographies of even his main characters. And yet we find them vivid and quick as our own selves because Shakespeare paints them as signs of contradiction. Gertrude is gracious and caring and yet torpid in her complicity with loathsome murder. Falstaff is both the antipode of the perfect gentle knight and yet rhetorically he evokes a luminous nobility. I hold a special place in my heart for Barnardine in Measure for Measure, who grumbles the morning of his execution not because he fears death but because he prefers to keep dozing in his cell.

We credit the incidents in biographies only because we trust the soundness of the research methods, not because we would find those lives convincing in a fictional story. A real human being enfolds entirely too many contradictions to become a convincing character in an imaginative story, where the intellect must fasten itself to a type, since this is what our minds are normally capable of seizing hold of. If the miser gives away his fortune in the fifth act, if the coward suddenly fights to the death, the mind winces and withdraws; every character no matter how profound must have a certain underlying periodicity. Shakespeare’s characters begin as types, and yet he inflects then just enough toward the true contradictory nature of the human spirit so that they remain dramatically viable while also incomparably vivid. (“There’s a divinity that shapes our ends, / Rough-hew them how we will…”) Cliché, then, is not the enemy of great literature, so much as its crude building material, which the artist must mold with difficulty to bring forth his vision. The modernist project to dispense with cliché at the outset has made artworks as slippery as fish and bleak as bus stations. In a modernist work, the artist no longer stoops to requisition cliché and ennoble it through his efforts—which was his real business.

Houellebecq’s characters are supposedly clichés, and so they are. We have seen, though, that cliché plays an integral role in our daily existence. Most reflective people, giving an honest assessment of their lives, would own that the currents of circumstance have brought them asymptotically closer to cliché, despite their tough swim strokes against the current of fate: while the innermost life of a person still has something irreplaceable about it, the obvious qualities of any given person feel increasingly prefabricated and mass-produced. Supposedly free to be anything they want to be, many people in fact furnish their personalities with a mail-order “starter kit,” allowing them to become “unique” by adopting wholesale the opinions and consumption habits shared by millions of others who are unique in the exact same way. “It was essential I do something for the 31st [of December],” thinks one of Houellebecq’s characters, panicking in his loneliness, “People do something, for the 31st.” Increasingly deriving their sense of worth from an ever-widening sphere of public opinion whose judgments are inscribed forever on the internet, people come to consider the crude categories that we apply to others not to be a necessary evil but the only yardstick of truth—not only with respect to others but also to themselves. What the French call amour-propre becomes the sovereign of every consciousness. In sum, the inner temple at the heart of every human being is forgotten, its sacred fires are veiled, and people become hideously consistent, and unashamedly so: witness the venal facility with which many schooled in psychobabble are able to “tell their story” at the drop of a hat, as though any human soul were reducible to a slick and single narrative.

And yet contemporary writers sometimes give the impression that they believe that the goal of imaginative writing is to demonstrate that no one, absolutely no one, embodies cliché and that each of us is resplendently unique. To recover the truth out from beneath the sawdust piles of glib social judgment is a fine aspiration. But what should the writer do when this glib social judgment is increasingly self-inflicted? The writer against cliché finds it unbearable that we should a judge a man by how much or little wealth, honor, fame, power, or pleasure he has accumulated. But how much more heinous is it when that man judges himself by these standards, and can conceive of no others? Obsessed with securing these clichéd goals, he strangely loathes what he obsessively pursues. “He hated it and loved it, as he hated and loved himself,” as Gandalf said about Gollum pursuing the ring; “I have coveted everything and taken pleasure in nothing” is the epitaph Guy de Maupassant suggested for himself.

But what else could they have pursued besides cliché when acculturation occurs now through the deceptions of mass media? An apprentice to a cutler in the olden days watched not only how forks were made but how his master behaved toward his patrons and subordinates, toward his children and maybe toward his God. He saw the better part of the man that he aimed to imitate. But a child watching television thinks bit-actors are gods because he never witnesses the empty and self-loathing expression that most actors assume a few breaths after the cameras they crave are flicked off. The unmediated, variously smelly people around the child are hounded by petty frustrations and aren’t, by the way, on T.V.; and the child sees this. But the man on T.V. with bleached teeth lives in a world of perpetual, sun-dappled ecstasy. Culture is imitative, so why not become the happy man in his electrical Eden, and not the fleshly local people who yawn and yammer and fail? But the child and his adult successor never knew this celebrity they worshiped, only his poisonous abridgement. The media pictures are always a vicious abstraction from the real, and their consumers will confuse the abstract for the real. A character in Houellebecq reminisces that long ago he “started seeing an analyst. I don’t remember much about the experience—I think the guy had a beard, but I might be confusing him with someone in a film.” Thanks to the miracles of technology, social media has now empowered millions to broadcast similar derangements; the consequences are still in their infancy, and baby Mordred will grow up.

Don Quixote wanted to become a knight errant; Emma Bovary, the heroine of a romance novel; Raskolnikov, a sort of Napoleon. They were aiming for models presented to them, in fact, by the media of their day—the books and newspapers that seem like the initial, ominous trickle portending the memetic torrent that now rushes into our phones and earbuds. But the layer of media-induced imitation resting on the life of Emma Bovary, say, was a light one, and the contrast between her dreams and her circumstances was Flaubert’s subject. Our situation is qualitatively different. Every day, new aspects of social life become mediated by mass communication, alloyed by posts, adulterated by podcasts. If, as Pessoa tells us, “[n]o intelligent idea can gain general acceptance unless some stupidity is mixed in with it” and “[n]othing passes into the realm of the collective without leaving at the border—like a toll—most of the intelligence it contained[,]” then the global dissemination of ideas acts like sulfuric acid poured on the wisdom won over generations. These theories must be crude to propagate; and because they are crude, they are false. We are lodged in a machine for the generation of false theories. Internet ideas arrive as fragments and resist the correlation present, for good or ill, in a book or a curriculum. Under the reign of universal streaming content, our social models and intellectual prompts are both detachable and rigid, as any mechanical product must be, and our own minds become detachable and rigid, since you are what you eat. Like the legendary invisible man who can be seen only by the clothes he wears, we see others and also ourselves only because we drape individual human beings in a swelling multitude of prefabricated and inflexible categories.

A novelist honestly depicting this milieu must depict characters who are clichés, because they chose cliché—no, they craved cliché with every fiber of their being. They grew up bowing to clichés, and they spent the summertime of their lives ascending to the altar of cliché. People now are embittered not because they ended as clichés but because they failed to embody the cliché they so desired.

Given the state of the world, Houellebecq must be acquitted on all cliché charges and issued a formal apology. Although he deals in exaggerations—“Was it possible to think of Bruno as an individual? [….H]is hedonistic worldview and the forces that shaped his consciousness and desires were common to an entire generation . . . . His motives, values and desires did not distinguish him from his contemporaries in any way.”—they are meant as gunshots to break through the din and bring our opinions back into balance. Consider, as the last note on this topic, the following description from The Elementary Particles:

In 1950 Francesco di Meola had a son by an Italian starlet, a second-rate actress who would never rise above playing Egyptian slaves; eventually, in the crowning achievement of her career, she had two lines in Quo Vadis. They called the boy David. At fifteen, David dreamed of being a rock star. He was not the only one. Though richer than bankers and company presidents, rock stars still managed to retain their rebel image. Young, good-looking, famous, desired by women and envied by men, rock stars had risen to the summit of the social order. Nothing since the deification of the pharaohs could compare to the devotion European and American youth bestowed upon their heroes. Physically, David had everything he needed to achieve his ends: he had an animal, almost diabolical beauty; his eyes were a deep blue; his face masculine but refined; his long hair thick and black.

This is utter, rigid, superficial cliché injurious to creative writing everywhere. It also happens to be perfectly plausible and just. Connection to celebrity, capacity for sexual indulgence, and degree of physical beauty: walking among us in their millions are those for whom these categories exhaust their self-understanding. And yet Houellebecq is the merchant of cliché! “The nineteenth century dislike of Realism,” wrote Oscar Wilde, “is the rage of Caliban seeing his own face in a glass.”

4. The Obscure Sense of the Truth

Houellebecq has surmised that his work appeals to readers because “you sense obscurely that it’s the truth.” If the truth entails our conducting sociological soliloquies within and congealing into sought clichés without, this sense must feel like the suffocation of a nightmare, even if it comes slathered in the pleasure of his novels. Houellebecq is resolutely bleak in all his prophecies about human existence—or nearly so. At the end of his latest novel Serotonin, the protagonist, having slogged through a life of selfishness, betrayal, loneliness, confusion, and stretches of vacuous pleasure, holes up in a Paris apartment with a nearly physical ache to commit suicide, and the reader senses it must come. But the death is not depicted. The novel ends instead with the following passage:

God takes care of us; he thinks of us every minute, and he gives us instructions that are sometimes very precise. Those surges of love that flow into our chests and take our breath away—those illuminations, those ecstasies, inexplicable if we consider our biological nature, our status as simple primates—are extremely clear signs.

And today I understand Christ’s point of view and his repeated horror at the hardening of people’s hearts: all of these things are signs, and they don’t realise it. Must I really, on top of everything, give my life for these wretches? Do I really have to be explicit on that point?

Apparently so.

I have not yet read any Houellebecq (although I do have a copy of ‘Seratonin’ waiting for me at the library), but I wonder what other contemporary novels (or novelists) you find worthwhile. I do agree with your appraisal of many of today’s novels, the great majority of which leave me cold, even the widely acclaimed ones.

Comments are closed.