West Palm Beach, FL. My university’s honors program is a “great books” program, which means we take young people and expose them to very old books. In the spring, we start sophomores in our “Humanism & Reform” class with Petrarch’s Secretum. Petrarch is one of the fathers of the Renaissance, but this book does not have the kind of confidence in humanity that students will come across in Oration on the Dignity of Man. In Secretum, Petrarch composed a fictional dialogue between himself and St. Augustine, in which he largely takes himself to task. The book and the conversations that result demonstrate both the value, in general, of reading works from the past and the specific benefits of reading Petrarch’s seemingly ancient dialogues at a young age.

Petrarch opens his dialogues with St. Augustine overwhelmed and miserable. The depth of his suffering makes students wonder if he is experiencing clinical depression or at least a mid-life crisis. He wants to be delivered from his misery. Thankfully, Augustine assures him that “every man who desires to be delivered from his misery, provided only he desires sincerely and with all his heart, cannot fail to obtain that which he desires.” Petrarch is happy to hear this, but wonders about the role of circumstances, such as the loss of a family member, etc. Augustine reassures him that his misery is escapable because it is his own fault, misery comes from sin. Petrarch can rise from his current circumstance, but one of his first steps should be to “practice meditation on death and on man’s misery.”

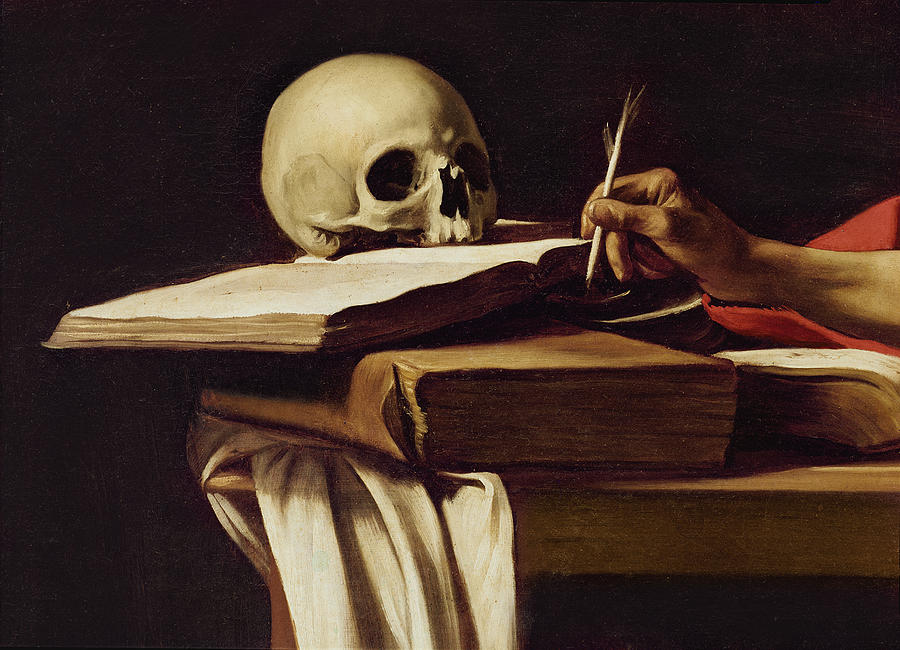

One of the benefits of reading old books is to experience surprise. As Fran Lebowitz reminds people in the Netflix series, Pretend It’s a City, “a book is a door, not a window.” Despite the resurgence of memento mori, it’s unlikely in 2021 that a depressed person would be told by a spiritual advisor that their misery is entirely their own fault and that the first step to healing is to contemplate their death. And not just in a general way, but, as the fictive Augustine puts it, “we must picture to ourselves the effect of death on each several part of our bodily frame, the cold extremities, the breast in the sweat of fever, the side throbbing with pain . . . the cheeks hanging and hollow, the teeth staring and discolored . . . the lips foaming, the tongue foul and motionless.” Such advice sounds quite strange to my students, but engaging the past should be a cross-cultural experience. And one benefit of a cross-cultural experience is a new awareness of our own cultural assumptions.

When students consider the kind of advice that Petrarch gives himself through St. Augustine, it displaces their everyday reality. What seemed “natural” in relating to misery is now shown not to be unchanging and universal. This does not necessarily lead students to reject their own present-day culture, but it should cause them to examine and argue for their own approaches. This is a step in the self-examined life, but it is also a step toward recognizing that there are more choices in life than we may at first realize. Voices from other ages are helpful in this endeavor.

Petrarch is one of the fathers of the Renaissance because of his reverence for ancient texts and his lead in the Renaissance humanism that not only brought back old ways of learning but sought to integrate the classical and the Christian. Secretum is an imaginary dialogue with St. Augustine, but much of the advice is cribbed from the Stoics. By their sophomore year in our honors program, students should be able to trace the threads of the different philosophies that Petrarch is weaving together. They should also be able to have a conversation about how they can take ideas and concepts from different eras and relate or integrate them into their own worldview. This is the kind of intellectual formation that college is all about, a formation that includes knowledge of specific philosophies and approaches for engaging other ideas and perspectives.

In On the Shortness of Life, Seneca advised that we can choose our own “intellectual parents” from among the thinkers of the past. Petrarch’s use of St. Augustine in Secretum very clearly shows students one way in which Seneca’s advice can be put into practice. And it is an interesting way. If Alan Jacobs’ recent book, Breaking Bread with The Dead, encouraged us to wrestle with the authors of the past, Petrarch lets the dead wrestle with him. His Augustine pulls no punches. When Petrarch protests that he has repented of his sins and tried to do better, Augustine replies “your tears have often stung your conscience but not changed your will.” He has similar lines throughout. Petrarch has turned Augustine into the ultimate accountability partner.

Petrarch’s Secretum exposes students to a new level of introspection and self-examination. When Petrarch tries to blame his problems on the world around him, Augustine returns the focus to his own flaws. When Petrarch identifies some of his strengths, Augustine reminds him of his weaknesses. Petrarch has read many books and feels he has knowledge of many things, but Augustine urges him “whenever you read a book and meet with any wholesome maxims by which you feel your spirit stirred or enthralled, do not trust merely to the resources of your wits, but make a point of learning them by heart and making them quite familiar by meditating on them.” At times Augustine seems harsh, but, then we remember, it is Petrarch speaking through him. The closer that students examine the book, the more they are prompted to consider self-examination.

Whether or not Petrarch’s approach is helpful for depression, some elements of it are helpful in the setting of a college campus or our country at large. Our culture today has an abundance of criticism of others, but a shortage of self-criticism. We fail to discern the difference between “canceling” and “consequences” not just for others, but also for ourselves. In the New Testament, the Apostle Paul called out many bad behaviors in others, but he also referred to himself as the “chief of sinners.” Very few leaders today, religious or otherwise, are as comfortable identifying their own flaws as they are the flaws of others. Today’s college students are tomorrow’s cultural leaders, and a book like Secretum helps our honors program encourage the practice of healthy but rigorous introspection.

Lastly, Secretum is a good book for sophomores precisely because Petrarch speaks not just from another era, but from another stage of life. Petrarch doesn’t just write from the 1300s, he writes from middle age, which is equally mysterious to most college students. Reading about his emphasis on memento mori, students consider that they may not, in fact, live forever. They should make the most of their time. And when Petrarch uses Augustine to call himself out for being bound and dragged down by the “chains of love and glory,” students are forced to consider what it is they are pursuing, in college and in life.

Toward the end of the book, Augustine asks Petrarch, even if he could guarantee a long life, “do you not find it is the height of madness to squander the best years and the best parts of your existence on pleading only the eyes of others and tickling other men’s ears, and to keep the last and worst—the years that are almost good for nothing—that bring nothing but distaste for life and then its end—to keep these, I say, for God and yourself, as though the welfare of your own soul were the last thing you cared for?” When we read Petrarch together in class, college sophomores confront that question. And it is a good question not only for sophomores, but also for all of us.

Well said Dr. Stice. Petrarch’s rumination on death is especially relevant to the global crisis of the day. The self-examination of Petrarch and the other Great Books is especially important for our time of libertinism. I pray the PBA Honors Program really does produce graduates of thoughtful introspection and virtuous character.

Comments are closed.