Parker, TX. Larry McMurtry’s best novels start slow. He could stomach only one re-reading of a manuscript, and he was famously resistant to editing. Indeed, his novels read like solid second drafts. You couldn’t call his prose lapidary, let alone elegant.

Yet, after a couple pages of Patsy Carpenter eating a Hershey Bar while parked in a rodeo arena parking lot (Moving On) or Augustus McCrae watching two pigs eating a rattlesnake (Lonesome Dove) or Emma Horton folding laundry (Terms of Endearment), you’re so invested in his characters that you’d follow them through three-hundred pages of quotidian experience, if McMurtry chose to lead you in that direction to prove a point. But he doesn’t. Things happen in McMurtry’s novels, but at his pace and often in ways that seem beyond the agency of his protagonists. Whether he takes us to the Texas frontier or to 1970s Houston, his prose never gets in the way of his story. He moves ahead with the precision and simplicity of one of the McMurtry boys telling a story on the front porch of the family ranch house in Archer County, Texas.

Still, so many passages have stayed with me over the thirty years since I first read Horseman Pass By. In All My Friends Are Going to be Strangers, the young novelist Danny Deck literally feels Texas behind him as he leaves for the West Coast:

At dawn we went through El Paso. It was strange leaving Texas. I had no plans to leave it, and didn’t know how I felt. I drove on into New Mexico, Sally still asleep. Then I really felt Texas. It was all behind me, north to south, not lying there exactly, but more like looming there over the car, not a state or a stretch of land but some giant, some genie, some god towering over the road. I really felt it. Its vengeance might fall on me from behind. I had left without permission, or earning my freedom. Texas let me go, ominously quiet. It hadn’t gone away. It was there behind me.

I never met the notoriously prickly McMurtry. I tell myself this is for the better since my encounters with my literary heroes have been mixed. Two were so arrogant that no I longer want to read them. Two others were so helpful and avuncular—even though I’d asked nothing of them—that I can’t maintain a proper critical distance from their work. Yes, most writers are better read than met. When I learned of his death on March 25, I immediately thought of William Styron’s farewell to Faulkner: “and now for the first time I am stricken by the realization that Faulkner is truly gone. . . Dilsey and Benjy and Luster and all the Compsons, Hightower and Byron Bunch and Flem Snopes and the gentle Lena Groves—all of these people and a score of others come swarming back comically and villainously and tragically in my mind.” I’m struck by the reality that McMurtry is gone, of course, but more by the realization that what we know of Emma Horton, Aurora Greenway, Danny Deck, Jill Peel, Clara Allen, Augustus McCrae, Woodrow Call, and Pea Eye Parker will have to be enough.

Periodically, McMurtry would look out over his home state, take stock of the literary landscape, and inevitably find it lacking. By September 1981, when he considered his fellow Texas authors in “Ever a Bridegroom: Reflections on the Failure of Texas Literature,” first presented as a lecture at the Fort Worth Art Museum, and published the following month in Texas Observer, he’d already written seven novels and an essay collection. At the age of 45, he was arguably the most accomplished writer Texas had ever produced. He came at his task with considerable authority and little tact, but that was the point. He began by tearing into the “Holy Oldtimers,” folklorist J. Frank Dobie, historian Walter Prescott Webb, and Roy Bedichek, probably Texas’s three most loved and revered writers through the 1960s.

On Dobie: “Less than two decades after his death, one finds [his] twenty-odd books a congealed mess of undifferentiated anecdotage: endlessly repetitive, thematically empty, structureless, and carelessly written.” (I want to believe this excoriation had nothing to do with Dobie’s refusal to review Horseman Pass By.)

On Bedichek: Excellent prose, but his bucolic essays are “almost a retrograde form,” a “nostalgic retreat from increasing urban realities.”

In the works of Webb, McMurtry detected a “first rate mind,” but found The Great Plains “dull and rather wooden.”

In the stories of Katherine Ann Porter, he saw “a fine talent . . . but a talent seldom either fully or generously put to use.”

You get the picture. John Graves, Tom Lea, Larry King, and several other heavyweights receive more or less respectful if mixed reviews. Never one to spare himself, McMurtry calls Horseman Pass By and Leaving Cheyenne “juvenilia,” and chides critic A.C. Greene for including them in The 50 Best Books on Texas. Only Houston native Donald Barthelme and poet Vassar Miller receive enthusiastic praise.

For all his harshness, McMurtry simply wanted better for his home state. Better readers, better writers. In his view, the only way to achieve those ends was to break up the clubby literary culture and end the obsession with an idealized rural past. He wanted “hard-nosed, energetic, and unintimidated local critics.” As much as he despised literary provincialism and argued for a turn from rural to urban literature, his focus remained on Texas: “Minnesota hasn’t produced a great literature either, nor has Idaho, nor perhaps even California. Fortunately, I am not from any of those places, and their failings are not my concern.”

Three years later, he submitted the manuscript of Lonesome Dove, a sprawling novel about three Texas Rangers driving a herd of longhorns from South Texas to Montana. The novel won the 1986 Pulitzer Prize for fiction and spawned what many critics and millions of fans consider the finest television miniseries ever produced.

From publication on, McMurtry claimed that he wrote Lonesome Dove to de-mythologize the frontier era and the brief heyday of the cattle drive and cowboy that followed. Certainly the trail of death and sorrow left in Hat Creek Cattle Company’s dusty wake reminds us of the cost of monomania and outsized ambition. So, yes, head ‘em up and point ‘em north. But add gang rape, castration, torture, and the hanging of an old friend. Of course, similar themes had been explored in novels and movies, but nobody had woven so many disparate threads into such a meaningful, satisfying whole. McMurtry drew on memoirs of the nineteenth century drovers, the friendship between Charlie Goodnight and Oliver Loving, and, by all appearances, the work of J. Frank Dobie.

But in stripping away sentimentality and cliche, McMurtry exposed the human flaw and stoicism that made Lonesome Dove’s characters at once relatable and heroic. In “Taking Care of Lonesome Dove,” Stephen Harrigan calls the novel “a sacred piece of Texas literature” and quotes screenwriter Bill Wittliff: “‘That’s one of the things Lonesome Dove is about: the fact that we all somehow believe those are the guys we came from.’”

Therein lay the rub that worsened into a gall. Lonesome Dove, the novel and miniseries, became too beloved by the wrong sort of people. Literary tastemakers had long since taken McMurtry’s advice to heart and were uninterested in if not contemptuous of the old myths. Nothing seems likelier to get on the nerves of literary types more than commercial success built on the enthusiasm of old men. Recently in the Los Angeles Times, critic David L. Ulin wrote, “I am a Lonesome Dove apostate. It’s enjoyable enough to read—all of McMurtry’s books are—but I can’t help considering it a retrenchment, the work of a writer no longer sure of himself or his own audacity, falling back on the familiar forms.”

Never mind that Lonesome Dove began around 1971 as a movie script that lay undeveloped for 12 years before McMurtry bought back the rights and spent several years shaping the story into a novel. He’d been thinking about the tale before publication of Terms of Endearment, perhaps the best-loved of the Houston novels, and nearly a decade before “Forever a Bridegroom.” McMurtry never seemed sheepish about contradicting himself.

As for Lonesome Dove being a “retrenchment,” the work of a writer who’d lost confidence and audacity, I don’t see why a novel of manners—a right venerable form by the 1980s—must be more audacious than an historical novel of Melvillian sweep and ambition.

In fairness to Ulin, he does quote McMurtry expressing ambivalence about the public’s interpretation of Lonesome Dove: “I thought I had written about a harsh time and some pretty harsh people, but, to the public at large, I had produced something nearer to an idealization; instead of a poor man’s Inferno, filled with violence, faithlessness and betrayal. I had actually delivered a kind of Gone with the Wind, of the West, a turnabout I’ll be mulling over for a long, long time.”

Mull as he might over the shortcomings of his Pulitzer-winning novel—or the limitations of the reading public—McMurtry followed with a sequel, Streets of Laredo (1993) and two prequels, Dead Man’s Walk (1995) and Comanche Moon (1997), none of them as good as Lonesome Dove nor as bad as critics claim. He wrote Streets of Laredo while deep in depression after open heart surgery. Not surprisingly, it’s the bleakest in the series, and, at a glance, seems to bury any remaining shard of frontier myth. Beyond ahistorical provocations involving Judge Roy Bean, Streets of Laredo rewards careful readers who’re willing to suspend expectations.

Woodrow Call, the stoical Ranger of Lonesome Dove has been hired by a railroad concern to hunt down a young, cunning bandit named Joey Garza. Now without his trusted partners Gus McCrae and Josh Deets, Call encounters various psychopaths during his travels in southwest Texas and Mexico. Though still a formidable man hunter, a legend whose name brings comfort along the remoter reaches of the erstwhile frontier, Call underestimates both his deadly quarry and his own limitations. In the wilds of the Chihuahuan Desert with Lorena, the two-dollar whore in Lonesome Dove who’s now a schoolteacher married to the gentle old ranger Pea Eye Parker, Call falls victim to failing eyesight and declining instincts. Joey Garza destroys Call’s right leg and left arm with three shots from a large bore rifle. At his instruction, Lorena nicks up his Bowie knife on a rock, then resharpens the blade into a saw with which she amputates his leg just above his knee. The following day, in the village of Ojinaga, a doctor takes off Call’s mangled arm.

Call survives only to live in a shack at Quitaque, on the edge of the Caprock Escarpment in West Texas. A gentle, blind girl looks after him and entertains him with stories. Yet he refuses to be useless. He spends hours compulsively sharpening blades. Knives, ax heads, a scythe. He needs the scythe to be razor-sharp.

We might imagine McMurtry and the few urban critics who took the novel seriously, thinking, There’s your precious myth, Texas! Right on cue, a young cowboy employed by the legendary plainsman Charlie Goodnight asks about Call. “I’ve always heard he was the greatest Ranger of all . . . but look now . . . sharpening sickles in a dern barn.”

Despite what he might’ve said about his intentions, I believe McMurtry knew that Woodrow Call, old and frail, one-armed, standing on one leg, sharpening a nicked-up scythe, would loom larger than life in the imaginations of the myth keepers.

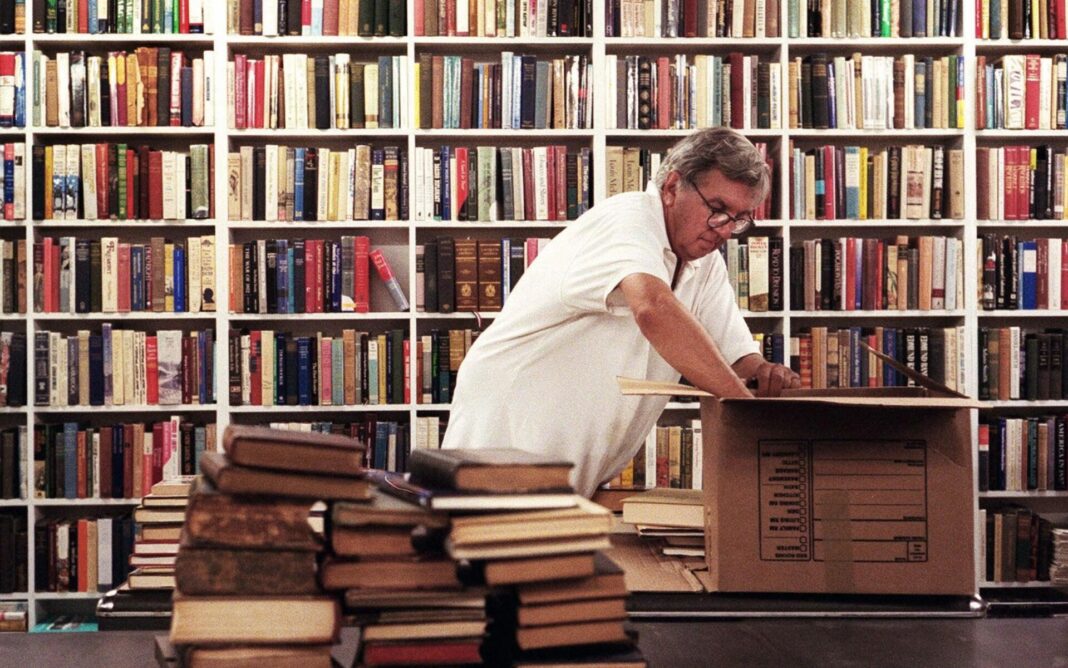

McMurtry wrote and spoke of ineluctable decline in a writer’s power. In 1997, he announced that he would write no more fiction. Then, true to pattern, he published Duane’s Depressed (1999) and started work on the Berrybender Narratives, a four-novel series set in frontier Texas and the West. He and Diana Ossana, his longtime writing partner, won an Oscar in 2005 for his adaptation of “Brokeback Mountain.” I could go on. He added to his list of contemporary novels, but Larry McMurtry, son of Archer City, Texas, Stegner Fellow, friend of the Merry Pranksters, Antiquarian Book Dealer, president of PEN America, pal to Susan Sontag, Hollywood screenwriter, husband to Ken Kesey’s widow, could never give up the old Texas and its enduring themes.

I want to attribute McMurtry’s decision to kill off the beloved Augustus McCrae and the incorruptible Josh Deets in Lonesome Dove, and to spare Woodrow Call, to something deeper than artistic whim. Since he left us, I’ve often imagined the old novelist at his manual typewriter before dawn, knowing his best work is behind him, tapping out five pages a day, every day.

A few times every autumn, on my way to hunt quail on the Rolling Plains south of Childress, I drive through the tiny unincorporated community of Thalia. Not the fictional Thalia of The Last Picture Show—likely modeled on Archer City—but a wide spot in the road that was never large enough to accommodate Jacy, Sonny, and Duane. I doubt I’ve ever passed through without thinking of the Thalia novels. For a while yet, old McMurtry will loom over my literary landscape like Texas loomed over Danny Deck as he left El Paso: Like some giant, some genie. He hasn’t gone away.

I’m so grateful that you’re one of those seemingly rare writers that are both great to read AND meet. Nice article! Wish my dad could have read it. He always did love Lonesome Dove.

Tamara, your comment means so much. Thank you. I miss your dad more than I can express. And I miss y’all.

Comments are closed.