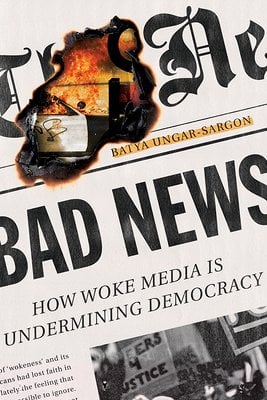

Beaverhead County, MT. In his book Bloodlands, historian Timothy Snyder observed that “It is not obvious that reducing history to a morality play makes anyone moral.” This comment could have been the epigraph of Newsweek deputy opinion editor Batya Ungar-Sargon’s recent book on the scurrilous role “woke” journalism plays in the American public square. In fact, the author contends, the media bears its share of responsibility for the fact that there is no longer any American “public square” worthy of the name.

In brief, Bad News tells the following story: once upon a time, journalists actually cared about the working class and local communities. Newspapers focused on local issues about which local people cared. Benjamin Day’s invention of the penny press comes in for particular attention here. However, the demographics of the journalistic profession changed, and the New York Times emerged with a new business model predicated on making sure that its subscriber base included no one without the money to buy the sorts of things advertised in its pages. Journalism became an incestuous occupation, where our journalistic elites tell our political, cultural, and economic elites nice things about themselves that will comfort the already comfortable. (More on afflicting the afflicted, shortly). In the author’s telling phrase: “If you want to know what makes America’s educated liberal elites emotional, you only have to open the New York Times to find out” (128).

Now enter the digital age, social media, and the thinly concealed neo-racism of our current anti-racist discourse, and in Ungar-Sargon’s telling you have the toxic soup that passes for our current “public square,” in which racism has become that ubiquitous hammer for which everything is a nail. For those who have bought into the postmodern story, according to which appeals to “objectivity” only mask attempts to gain Power, racism becomes the perfect cause célèbre. Like the biblical Pharisee who prays in public, anti-racism allows the elite to signal their righteousness, while relieving that same elite of responsibility for actually doing anything about it, since racism is baked into the American cake a la the 1619 Project. Put another way, for our elites, racism is the gift that keep on giving. In Ungar-Sargon’s telling, this is the story of woke media; faux-democracy and an increasingly class-divided society are and will be the results of that media’s domination of the news.

While the meat of Bad News is a sustained polemic against a journalistic establishment increasingly populated by faux-liberal trust-funded twitterati, Ungar-Sargon’s epilogue does spend some time discussing what we might do to ameliorate or even reverse this sorry state of affairs. That said epilogue begins with reference to Christopher Lasch predisposes me to look favorably on her suggestions, but if the problems of our public discourse are as severe as she makes out, I’m skeptical that her remedies are up to scratch. Perhaps a Front Porch ethos could help make up for this lack. Time will no doubt tell.

My least-favorite bumper sticker of all time reads, “If you’re not outraged you’re not paying attention.” As a remedy for this sort of dopamine-fueled attitude, the author suggests that we refuse to bow to the media outrage machine. This is an excellent suggestion—fixing our individual behaviors should always be number one on our list. No argument there. Ungar-Sargon’s other suggestions are equally good. They include the need to understand why working-class people tend to a generally conservative outlook, refusing the old 60’s canard that the personal is political, and [re]discovering the virtue of humility.

So far so good, but Ungar-Sargon’s argument is that our moral panic over racism is really about Power. Driving home the point, she quotes Shelby Steele’s argument that the “original sin” of America isn’t racism as such, but “It is simply the use of race as a means to power” (206). If this is so, then it’s hard to see how Ungar-Sargon’s list of suggestions might register on the radar screens of her unholy alliance of prep-schooled journalists, opportunistic politicians, and woke big business, most of whom don’t give a damn about the lower classes and all of whom are insulated from the practical consequences of their ideas and policy decisions. That this is the author’s primary audience seems unlikely, given that Encounter is Bad News‘s publisher, and so I’m left with the rather ironic sense that I’m a member of an outraged choir to which the author is preaching. The public square does indeed run on outrage.

If neoracist wokery is both good for business and for the Machiavellian care and maintenance of political power, then I suspect that it will take a bit more than humility and zen-like rejection of the outrage machine to dethrone our self-appointed philosopher-kings. Kendi & Co. get rich and powerful by running what amounts to a combination blackmail scheme and protection racket on faux-masochistic white liberals, as John McWhorter has argued for some time. I see little in this book that might cause them to cease and desist.

So, I must confess my inability to muster up much in the way of optimism. Ungar-Sargon evinces a laudable desire to remind her elite readers (if there are any) that the “working class” is a diverse group that can’t be reduced to knuckle-dragging-racist-Trump-voting-deplorables. Rather, this group is populated by many thoughtful individuals and they are elites’ fellow Americans. Agreed. Arguably, though, this is less a fact that elites ignore to their peril, than it is a laudable aspiration that will also be ignored, probably to the financial benefit of Big Media and its customer base. While admiring the author’s appeals to common humanity, decency, objectivity, and so on, I’d offer two basic critiques of this point of view:

First, it assumes that democratic, civic engagement in the public square can proceed indefinitely under the tacit assumption that there aren’t actually any Right Answers that could and should compel resolution of any Big Questions that divide us. Chapter 11 is entitled: “How the Left Perpetuates Inequality and Undermines Democracy.” Ungar-Sargon considers herself a woman of the Left, which creates some interpretive tension. If the battle for the conscience of journalism is a stand-in for a larger battle for the soul of the Left, then Ungar-Sargon needed to write a rather different book to reach that target audience. If her diagnosis is correct, for example, why wouldn’t the woke left see “undermining democracy” as a feature, rather than a bug? However, if a rural-American communitarian conservative such as myself is her target audience, then the happy instance of a Big Media sea change won’t address the more basic problem that both Left and Right believe that the other side has been “undermining democracy” for years. To the extent that one side or the other is right about that, a news media less committed to self-aggrandizing ideological posturing might report that conflict more accurately, but it won’t do much to resolve those underlying disagreements either.

Second, however we choose to label our political and cultural tribes, I have to raise my children in this world and not some ideal alternative. I find myself unable to chalk up my losses—you win some, you lose some—to the vagaries of living in a Procedural Republic, in Sandel’s phrase. Therefore, I’m unpersuaded by Ungar-Sargon’s argument that the elites she portrays as stoking racial division to exploit me and my fellow hoi polloi, are also my fellow Americans. Put bluntly, if elite journalist circles are as bad as she says they are, then I don’t want them as neighbors in any other sense than the biblical one. Apparently the feeling is mutual, and in Ungar-Saron’s telling, they excommunicated me first anyway. In short, it is possible that the time for appeals to common humanity and so on, has passed, at least if Ungar-Sargon’s argument that elites would rather exploit the economic, political, and cultural benefits of continued inequality than do anything about it is to be believed. If this make me part of the problem, then so be it. When my private opinions carry as much cultural weight as the NYT opinion section, I’ll apologize, get rid of the smart phone and social media accounts I’ve never had, and enjoy a more participatory and congenial public square.

So how to assess this book’s value, then? For Porchers, I’d suggest that the answer is simply to keep doing what we’re doing: Remember Daniel Boorstin’s admonition that “The News” has always been a “pseudo-event.” (And if you haven’t read The Image, buy a copy from somebody other than Amazon). Get off social media, free yourself from the telescopic morality machine, get to know your neighbors, and keep your kids out of the Ivies so that you’ve got a chance of passing those attitudes on to the next generation. If Ungar-Sargon’s optimism is correct, then in so doing, we’ll be part of the solution anyway. And who knows, since Bad News‘s publication, John McWhorter has landed a regular column at the NYT. Perhaps this is a sign that heterodox opinions on matters racial may gain a hearing, in future.

If, however, we’ve passed some sort of tipping point and media’s dominant and dominating commitment to maintaining the status quo makes recovering a sense of national-level community a lost cause, then Bad News becomes an interesting story of major media’s role in making that happen. Here, Porchers should likewise stay the course. A future America governed by a tacit understanding that you live in California if you’re one kind of person and Texas if you’re another kind of person probably isn’t the worst possible outcome, even granting that the principle of the rule of law will suffer even more than it has already. Though possibly fanciful, this is still probably a more realistic future than the idea that our feudal lords will recover a lost sense of noblesse oblige vis-à-vis the Armani-watchless classes (see Ungar-Sargon discussing Joel Kotkin on this point, 240). There is a lot more money and prestige in perpetuating a racial narrative that does the opposite.

Either way, Voltaire and I can now return to cultivating our gardens, blissfully ignorant as to what our coastal elites are getting emotional about today.

This is excellent, Aaron, and both nuanced and insightful. Thanks.

“To the extent that one side or the other is right about that, a news media less committed to self-aggrandizing ideological posturing might report that conflict more accurately, but it won’t do much to resolve those underlying disagreements either.”

Exceptionally pithy in an incredibly incisive article. Thank you.

I recommend the century-old story by EM Forster called The Machine Stops:

https://www.ele.uri.edu/faculty/vetter/Other-stuff/The-Machine-Stops.pdf

By sheerest coincidence, my 17 year old grandson was visiting with me last week, and I had him read “The Machine Stops”.

“What did you think of it?”

“Everybody dies.”

“Everybody?”

“Except the homeless. They weren’t part of the Machine.”

There is hope.

I will say it’s “shocking”, but it’s really not at this point, to see “journalists” openly rooting for people, politicians, and other media outlets to be suppressed. What kind of “journalist” with the slightest bit of self-respect can cry about “disinformation” and root for censorship?

The problem isn’t that the media is “woke”, it’s that it’s cheering for censorship of those who aren’t.

“The problem isn’t that the media is ‘woke’, it’s that it’s cheering for censorship of those who aren’t.”

Wokeism has a prominent strand of Marcuse in its ideological DNA. The intolerance of ideas resistant to it is a feature, not a bug.

Comments are closed.