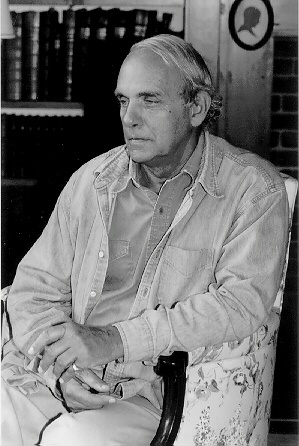

Atlanta, GA. Frederick Buechner, who died last month at age 96, had written two novels – 1950’s well-received A Long Day’s Dying and 1952’s much less successful The Seasons’ Difference – when he decided to go to seminary. He’d been unexpectedly, even bafflingly, converted to Christianity early that decade by the sermons of George Buttrick of Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church, but no one in his life thought seminary was a good idea. He records their reactions in one of his memoirs:

People who admired me as a writer were by and large either horrified or incredulous. Even George Buttrick, whose extraordinary sermons had played such a crucial part in my turning to Christianity, said it would be a shame to lose a good novelist for a mediocre preacher. And deep inside myself the issue was far from settled either. But for the time being it seemed dim and remote compared with the new life I was entering.

As it happened, Buttrick needn’t have worried: Union Theological Seminary, where Buechner matriculated in autumn 1954 and from which he graduated in early summer 1958 after a sabbatical, does not seem to have had any negative effect on his career as a writer.

It was, to be fair, something of a Golden Age for Union, the flagship seminary of liberal American Protestantism. While there, he read Karl Barth and Gerard Manley Hopkins with Reinhold Niebuhr and James Muilenberg, receiving along the way the theological and intellectual foundation for all his later work. Contrary to some of his obituaries, Buechner was never a pastor; his official title in the Presbyterian Church (USA) was evangelist, and the closest thing he ever had to a congregation was the cynical, skeptical sons of the rich at Phillips Exeter, where he taught religion from 1958 to 1967. It was, he reports, a wrenching and rewarding experience: “What those extremely intelligent, articulate, sophisticated young people were there to take potshots at were not just the religious ideas that I offered to their scrutiny, but my own recently acquired and little understood faith which was much of what gave meaning and purpose and richness to my life.” After nine years, he felt himself called again—this time to rural Vermont, where he’d spend much of the rest of his very long life as a full-time writer.

He wrote novels, fifteen of them, of which I think I’ve read nine. I must say, with all due respect to Buechner, that I don’t think he’s that great of a novelist. Many of his books are more or less adaptations: The Entrance to Porlock of The Wizard of Oz; Godric and Brendan of medieval hagiographies; The Son of Laughter of the story of Jacob and Esau; On the Road with the Archangel of the Book of Tobit; The Storm of The Tempest. They are worth reading, especially for people already committed to Buechner’s thought, but they are not, I think, where his legacy lies. I do like 1971’s bawdy, absurdist Lion Country, whose protagonist is converted by a Florida evangelist who is also (probably?) a child-flasher and by his sexy, secular daughter. But that novel sometimes feels as though Buechner is chasing John Updike’s notoriety, and its three sequels are substantially less appealing. Buechner’s best novel might well be John Irving’s A Prayer for Owen Meany; Irving was his student at Exeter and his neighbor in Vermont, and Prayer owes a great deal to Buechner’s language and thought. Contra Buttrick, I think we may have lost a mediocre novelist for a good preacher.

Or maybe preacher isn’t the right word. Buechner did publish two collections of his Exeter sermons, but the bulk of his nonfiction can hardly be called sermonic in any conventional sense of that word. Nor was he really a theologian, certainly not in the sense that his heroes Barth and Muilenberg and Tillich were. At least four of his books are autobiographies, and I think the best term for him is probably “memoirist” or even “essayist” – in the French sense of essayer as “to try.” Buechner in his nonfiction is always trying, unsystematically, to make sense of two realities too vast to make sense of: God and his own life. As a Presbyterian, he would surely have been aware of the opening paragraph of Calvin’s Institutes:

Nearly all the wisdom we possess, that is to say, true and sound wisdom, consists of two parts: the knowledge of God and of ourselves. But, while joined by many bonds, which one precedes and brings forth the other is not easy to discern. In the first place, no one can look upon himself without immediately turning his thoughts to the contemplation of God, in whom he “lives and moves.”

Calvin’s point is that our lives are incomprehensible until we have an understanding of God’s nature, which can’t happen without the “special revelation” of Scripture. Buechner reverses this schema without entirely discounting it.

His great insight – and I won’t claim that he is the first or only writer to come up with it, though I suspect he phrases it more strikingly than almost anyone – is that theology rests on autobiography: “If God speaks to us at all other than through such official channels as the Bible and the church, then I think that he speaks to us largely through what happens to us.” Thus his perpetual return to autobiography, direct and indirect. It’s not a coincidence that the most artistically successful of his novels is The Wizard’s Tide, which retells the central tragedy of his boyhood – his father’s suicide – as a semi-fairy tale, which is to say, as a place where the veil between nature and supernature is appealingly, appallingly thin. His point is that that veil is thin everywhere in our lives, if we have but the eyes to notice.

If there is a God who speaks anywhere, surely he speaks here, through waking up and working, through going away and coming back again, through people you read and books you meet, through falling asleep in the dark.

– The Alphabet of Grace

With this in mind, I will suggest that Buechner’s greatest book is neither novel nor memoir nor sermon collection but a book that inhabits the weird no man’s land between the three. I am talking about 1970’s The Alphabet of Grace, which I read for the first time as a high-school junior, then several dozen times since. Alphabet began as a series of lectures delivered at Harvard Memorial Church, and like a lot of lecture series, it neatly limns the contours of Buechner’s thought. The book is (very loosely) organized as a single day in which its author tries to find God’s presence. The alphabet alluded to by the title refers to the visible manifestations of the invisible. These manifestations are the language God uses to speak to us – a broken and insufficient language, but one that we can, after all, learn to speak haltingly and without much fluency: “If there is a God who speaks anywhere, surely he speaks here, through waking up and working, through going away and coming back again, through people you read and books you meet, through falling asleep in the dark.” A lovely thought.

This language sounds very much like Hebrew, the harsh and guttural language of Jesus’s Bible; if God has been speaking through Buechner’s life, it is at least occasionally a language of tragedy, of horror and defilement. There is, for one thing, his father’s suicide, which haunts every book he wrote, as it must surely have haunted every day of his life – But there are also the atrocities we all accumulate as the days turn into years and decades, the images that stick in our heads even when we only got them secondhand. One passage from Alphabet has stuck in my head for 23 years. Buechner is driving home from church one Sunday morning, “full of Christ,” when he unwisely decides to turn on the radio news. He learns that that morning, a five-year-old

had kept his parents awake all night with his crying and carrying on, and the parents to punish him filled the tub with scalding water and put him in. These parents filled the scalding water with their child to punish him and, scalding and scalded, he died crying out in tongues as I heard it reported on the radio on my way back from of all places church and prayed to almighty God to kick to pieces such a world or to kick to pieces Himself and His Son and His Holy Ghost world without end standing there by the side of that screaming tub and doing nothing while with his scrawny little buttocks bare, the hopeless little four-year-old whistle, the child was lowered in his mother’s arms.

This is not an easy faith that Buechner describes; it is a faith forged in the blast-furnace crucible of Ivan Karamazov. One of the most appealing parts of reading Buechner is the clear respect he has for skeptics and doubters and other unbelievers. At times he seems to wish he could not believe—but the quiet, insistent cough of grace in his life draws him back. In the one or two major crises of faith I’ve been through in my adult life, Buechner was always there to comfort me; no doubt he has also been there to comfort those who never heard the gutturals and sibilants of faith again.

Buechner understands, better than any popular writer I’ve ever read, the dialectic of the religious life, the interdependence of faith and doubt in the modern world. His literalizes this distinction in Alphabet by having an “interlocutor” – his Unitarian grandmother, and then a former student, younger and smarter than him – call into question any expression of faith he dares to make. When his interlocutor asks him to point to some “genuine, self-authenticating religious experience” that would prove the truth of his religion, Buechner, who has already narrated a few rather mundane experiences (branches clacking together, a weekend at a silent monastery, etc.) realizes what his interlocutor can’t: there’s no such thing as a self-authenticating religious experience, because the deniability of the experience is part of its power. The gaps of doubt in the fabric of faith allow it to breathe; the pockets of air in the dough allow the leaven of faith to expand. “Without somehow destroying me in the process,” Buechner wonders aloud, “how could God reveal himself in a way that would leave no room for doubt?” God’s partial withdrawal prompts us to chase him, even after he’s already caught us.

I love Buechner’s description of why he is a Christian, as I love everything else in this little book: “I happen to believe in God because here and there over the years certain things have happened. No one particularly untoward thing happened, just certain things. To be more accurate, the things that happened never really were quite certain and hence, I suppose, their queer power.” What strikes me here are the reasons Buechner doesn’t say he believes: there’s no enormous epiphany, no burning bush; nor is there an airtight chain of logic. Those things would allow him to communicate his faith to other people in absolute terms, which as it stands he cannot. But he can communicate it in rather more modest form, by narrating his own life. That sort of retreat into autobiography can be a cop-out; people can avoid arguments against their religious beliefs by treating faith as something merely personal. But I don’t think that’s what Buechner does. His books are not a diminishment of historic and intellectual Christianity. They are a translation of Aquinas, Barth, Calvin, and the rest into the language we all speak innately but are all too often deaf to: the language of our quotidian lives, in which the undifferentiated mass of uncertain “certain things” forms the alphabet of grace.

Image Credit: Claude Monet, “The Four Trees” (1891)

Postscript: I first came to Buechner through the work of the singer/songwriter Terry Scott Taylor, whose songs are replete with echoes of and quotations from The Alphabet of Grace and other Buechner books. Fans of Buechner would do well to seek out Taylor’s band Daniel Amos’s album Motor Cycle.

Ah, Daniel Amos (or DA). Taylor was also quite the fan of William Blake.

Comments are closed.