Wyoming, MI. In all the handwringing over so-called “populism,” much can be gleaned about our current politics when certain groups see their inferiors as exercising the franchise in the wrong way, meaning that the inferiors are pursuing their own interests rather than those of their more obviously enlightened counterparts.

I haven’t watched television news my entire adult life, but every now and then when I’m at the house of a friend who does watch the news I’ll give it my attention because I know I’ll learn something, although not typically what the newsperson wants me to learn. I’ll confess to the sin of being interested in a news broadcast when the Brexit vote happened, being largely captive in the home of a close Canadian friend. To the degree I had a stake in the outcome my sympathies were with the Brexiteers, even if I try to make it a policy not to stick my nose into other people’s business. Whether Great Britain stayed in the EU or not was their call, not mine, and I wasn’t going to get worked up about it either way.

What got my attention, however, was the way in which the CNN “personalities,” particularly globe-trotting and extremely earnest cosmopolitan Christiane Amanpour, breathlessly denounced the results rather than merely reported them, which in a happier time would have been her actual and only job. I’ve never given much thought to the EU other than taking it as yet another example of the dreaded path of centralization and bureaucratic control that is the enemy of democracy and not its expression. That was the moment, however, when it became clear to me that the defenders of the EU shared a common trait: they both believed and hoped that we had entered an era when nation-states, the building blocks of the international system for the last 400 years, would cease to exist. Their cosmopolitanism was a negation of the normal sentiments that people attached to the places of their birth. Being rootless global wanderers themselves, they couldn’t relate to these otherwise warm patriotic sentiments, and were not only dismissive of people who do have them, but contemptuous as well.

These issues came back to mind the other day when I was reading Mary Harrington’s recent essay on “Why the Nation-State Failed.” She defends the nation-state in these terms:

I’d have said something to the effect that nation states are the generally-accepted modern scale for the governance of a people in a particular place. That in modern times this governance usually (though not always) happens via some form of electoral democracy. I might have added that nations tend to map partly, though not exclusively, onto a culture, language, and history — and that over time they often have a reciprocal structuring effect on that people’s idea of themselves as a collective with common interests.

She argues, rightly in my view, that a good deal of the intensity of the conflicts in our contemporary politics results from disagreements about the nation-state itself and its concomitant idea of citizenship. One tell-tale sign is when a person or institution—and I’m referring here to virtually every college and university in this country—regard it as vitally important to “create global citizens,” which necessarily requires a displacing of more attendant loyalties. These institutions become instruments of detachment. Drive around this country and observe the communities where people predominantly fly American flags and compare those to communities where people are exclusively flying rainbow flags, with all their implications about “universal human rights.” I don’t have the data ready-to-hand, although I see an interesting project in my future, but I’ll wager dollars to doughnuts that those places track red and blue respectively. Both sides will call each other names, but at the root of the disagreement is the nature and fate of the nation-state itself.

Why, after 400 years, does the legitimacy of the nation-state as an organizing principle of political life suddenly come into question? We need not look far for the answer: it’s a result of the two world wars of the 20th century and the guilt and shame they generated. If nation-states are so incapable of keeping the peace, the thinking goes, we need to develop an alternative system, and it’s one that political thinkers have seized upon from time immemorial: the dream of a single, simple, universal society, administered by experts, that guarantees perpetual peace. The dream has three elements: a higher standard of living for everyone, which removes the central cause of conflict, and that higher standard of living can be achieved by the free trafficking of goods, services, and labor across borders, which is why the universalists favor mass immigration and hate borders in general; a minimalist moral underpinning that places the fig leaf of “human rights” over the idea that if everyone accepts everyone else exactly as that other person understands him- or herself to be, and that everything is licit so long as it doesn’t directly harm another person, we will have eliminated another cause of conflict (an example of this moral speculation is articulated in the UN’s latest “8 March Principles,” which, independent of the controversy, makes remarkable assumptions about what human beings are and are for); and a relatively stable security environment sustained by America’s global and largely unrivaled military presence.

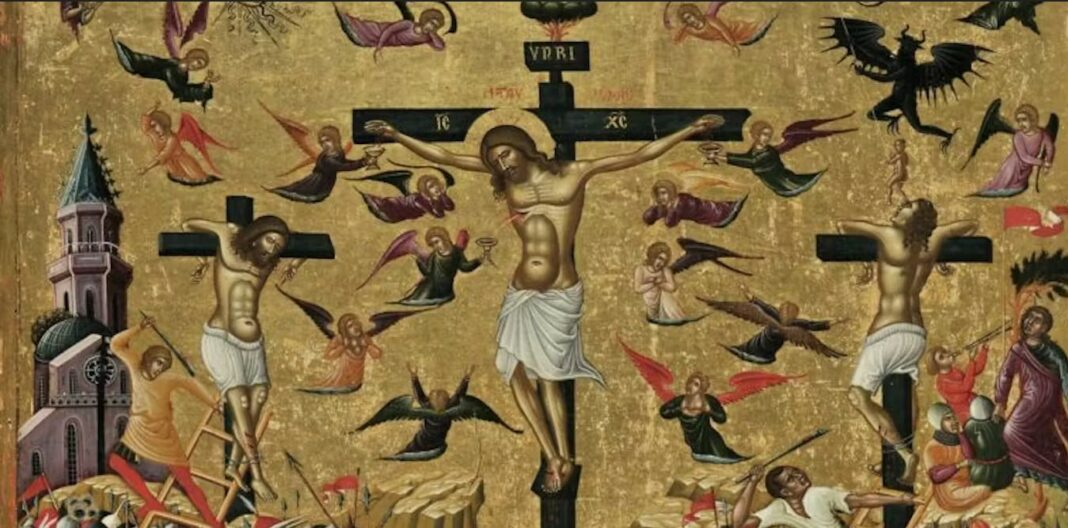

Mainly I want to return to this issue of guilt. My students know that I am an admirer of the work of Friedrich Nietzsche, whose central insight was that the West had already moved into a post-Christian age, and that the loss of the Christian foundation of the civilization would ultimately lead to the collapse of the civilization that was built on Christian beliefs and principles. What made this insight even more interesting was Nietzsche’s observation that we would still be in the presence of vestiges of the Christian era, and we would take the fragments of Christian ideas and beliefs and either hold them merely as personal preferences or relocate them to other parts of life. In his The Genealogy of Morals, he focused explicitly on the idea of guilt and realized that it is built into the human condition because of who and what we are, but without a mechanism for expiating guilt it would become a chronically toxic feature of our lives. We would end up in an endless cycle of guilt and blame with no way of finding absolution. Take contemporary debates about reparations, for example: independent of whether they are good policy or the right thing to do, they will certainly fail at their central aim, which is to effect reconciliation by discharging guilt. Some white people will still feel guilt and some black people will still withhold forgiveness mainly because, as Nietzsche foresaw, once the possibility of grace is forestalled, we are left with power, and the lust for power doesn’t have a price tag on it. Like the priests of Baal, the high priests of the new religion that has guilt as its central feature will wail and scream as loudly and as publicly as they can. They will put posters and signs on their doors and walls in hopes that judgment will pass them over.

The fundamental question all human beings face is “how can we atone for our sins?” Nietzsche argued that we were now living in a world where we faced the arduous task of “extending grace to ourselves,” precisely because we had rejected the one solution that Christianity had offered: Christ as the ultimate (meaning the last) scapegoat. As Rene Girard argued, communities attempt to resolve the problem of violence with a “lesser” violence by scapegoating someone whose guilt, they believe, is obvious. The community can reunite itself by visiting its violence on the scapegoat, and it will do this because the desire for unity and fraternity is in many ways as profound and extensive as is our tendency to sin and violence. We weary of violence and so we seek to cleanse ourselves of the guilt it brings by locating blame; and, here’s the key move, the source of sin is always outside of ourselves. As a result, we are presented with a simple solution to the problem: identify the cause and remove it. Nation-states cause wars? Well, then—get rid of nation-states.

The fact is that those who indulge universalist dreams don’t like complexity, and they especially don’t like it within themselves. They keep offering magical solutions: if we can just do this one thing, it will solve all our problems, and sometimes that one thing is as simple as removing someone they hate from office. Constitutional scholar Mark Tushnet took this impulse one step further. Confident that he was “on the right side of history,” he argued for the condemnation of conservatives whom he saw not as fellow citizens but as bigots. Again, the problem of sin and guilt is externalized:

For liberals, the question now is how to deal with the losers in the culture wars. That’s mostly a question of tactics. My own judgment is that taking a hard line (“You lost, live with it”) is better than trying to accommodate the losers, who – remember – defended, and are defending, positions that liberals regard as having no normative pull at all. Trying to be nice to the losers didn’t work well after the Civil War, nor after Brown. (And taking a hard line seemed to work reasonably well in Germany and Japan after 1945.) I should note that LGBT activists in particular seem to have settled on the hard-line approach, while some liberal academics defend more accommodating approaches. When specific battles in the culture wars were being fought, it might have made sense to try to be accommodating after a local victory, because other related fights were going on, and a hard line might have stiffened the opposition in those fights. But the war’s over, and we won.

Debates over the fate of the nation-state are largely driven by the fundamental problem of how we respond to guilt in a post-Christian age. Our politics will thus reflect the growing division between those who still believe the Christian message about forgiveness and those who will deal with guilt either by scapegoating or by denial. If the latter have indeed “won,” the cycle of violence will only intensify.

This essay originally appeared at the Ford Forum and is reprinted with permission.

As it happens, just last night I watched Ken Burns’s documentary on Huey Long, and evidence confirming the truth of your first paragraph is fairly prominent there. Long was certainly no saint and there is much to criticize about his methods and tactics, but the condescension on display in the film’s comments of the “elites” is quite sobering. Very similar to that expressed in the critiques of Brexit and MAGA, actually.

Tushnet: “My own judgment is that taking a hard line (‘You lost, live with it’) is better than trying to accommodate the losers, who – remember – defended, and are defending, positions that liberals regard as having no normative pull at all.”

That last clause is very telling. It’s not just that he believes non-liberal ideas are wrong. He believes they are fundamentally invalid and are basically indefensible (“no normative pull at all”). What’s there to “dialogue” over, in other words (at least after you’ve gained power)?

New documentary on Huey Long? Now, how did I miss hearing about that?

Not new — old! Came out in the 80’s I think, but I just recently found out about it.

Thanks! And I did see that one. Huey was such a fascinating individual. But I always suggest to anyone interested in that family to read Liebling’s wonderful book Earl Long, The Earl of Louisiana.

“nations tend to map partly, though not exclusively, onto a culture, language, and history”

Is he intentionally redefining the word nation, that according to wikipedia means “a community of people formed on the basis of a combination of shared features such as language, history, ethnicity, culture and/or society.” Or is he referring to the “state” part in the sloppy way that most contemporary people do, thinking that nation-state is a redundancy?

The nation-state is dying/dead because neither of the two dominant global powers of the late 20th century were nation-states, and the one dominant global superpower of the 21st century decided (or at least its “elites” did) to kill the form. There’s strong pushback now from much of the “third world” that people aren’t fully recognizing because it comes strongly separated (in most but not all cases) from “democracy”, so instead of it being talked about as “nation state” vs “empire”, it’s “freedom/democracy” vs “authoritarianism/dictatorship”, which suits the propagandists better.

Comments are closed.