John Klar and I have quite a lot in common. We both raise livestock on small farms. We both spend more time than the average guy seething about ethanol, crop subsidies, and regulatory capture. We both like good food and good pasture. Since he lives in the northeast kingdom of Vermont, I assume he likes winter at least as much as I do. We’ve both written about cows for this very website more than once! Given this, it is no surprise that I agree with quite a bit of the argument he makes in his new book, Small Farm Republic. The industrial food system has profound problems, from its impact on human health to its degradation of the environment to its mass mistreatment of domestic animals. Yet what stuck with me, what I’ve been ruminating on since reading Klar’s book, is how differently he and I diagnose the underlying ailment.

The subtitle — Why Conservatives Must Embrace Local Agriculture, Reject Climate Alarmism, and Lead an Environmental Revolution — is an obvious starting point. This is foremost a book written by a conservative, for conservatives. Klar wants to convince his fellow travelers that they should seek to promote individual human flourishing and strengthen the country as a whole by using farm and food policy to bridge the ideological divide. In pursuit of this admirable goal he employs the language of his tribe, which is probably a wise tactical move, but means your reaction to the book will vary depending on your political leanings. If you live in terror of the Great Reset and The Green New Deal, reading it will be like having a good talk with a like-minded friend. If you are a political outcast, you will find yourself nodding your head at one sentence and shaking it at the next. If you break out in hives at the first whiff of climate change skepticism or doubt about the efficacy of solar panels and EVs, you should still read Small Farm Republic, just keep a box of Benadryl close at hand.

But Klar is no bomb-throwing partisan. “Conservatives and liberals must unite to support small farms and local food production,” he writes. “There is no need to embrace global warming or even carbon dioxide as a culprit for conservatives to see the many benefits that follow. Democrats can fight the climate change battle separately while concurring on the many benefits proffered by Republican policy initiative favoring regenerative practices and local agriculture” (189). He repeatedly rebukes what he terms “Burn-baby-burn Republicans,” and he closes the book with an incisive critique of the official GOP environmental platform.

Unrelated to ideology, I want to mention how much I appreciate the clarity and energy of the language. Books by farmers often evince a fraught relationship with the written word, but Klar knows his way around a sentence, and he does a good job of concisely explaining complex topics, such as the need for more research into alternative farming methods. When he lays out specific policy prescriptions they are clearly put and at least on paper would appeal to voters across the political spectrum. Cash crop subsidies, the ethanol mandate, burdensome regulations, and rural land tax structures reflect the interests of industrial agriculture rather than small farms, with the interests of the voting public as a whole an afterthought. Klar argues for abolishing or reforming all of these.

While I would sign on to his proposed reforms, I nevertheless have two fundamental disagreements with the premises underlying the arguments in Small Farm Republic. Because the book is making a fairly constrained case — that conservatives should make common cause with centrists and willing liberals to craft a better farm policy — it assumes that you’re either already on the same page as Klar or are willing to trust his assessment that the reason the current system exists as it does is primarily political, and further, that the system itself is doomed. Here’s Klar on the first of these:

The economic and cultural destruction of family farms has been no accident, nor has it simply been a by-product of ‘progress.’ On the contrary, as farmers who once dominated the nation’s countryside (and legislatures) were pushed out by ambitious, urban, white-collar ‘experts,’ ever-larger corporate actors have been able to manipulate tax laws, regulations, and subsidies to eradicate those small farms for the expansion of large-scale agricultural (and chemical industrial) interests. (57)

In this telling, the decline in the number of small farms across America can be attributed to “ambitious, urban, white-collar ‘experts’” who have gamed the system in order to drive out small farms. Klar restates the claim a couple chapters later, “A persistent fallacy is that small-scale agriculture cannot compete economically with large industrial methods. The opposite is true for most crops: small-scale farming can and will be profitable, absent artificial regulatory hurdles that destroy profit margins” (93). If this is the case, then rallying a political movement to repeal onerous regulations makes good sense: level the field and small farmers will once again be able to plant something on it.

I wish I shared this view, but I simply don’t. I think ‘progress,’ by which I mean advances in agricultural technology, has been by a wide margin the single biggest factor in the consolidation of agriculture, not just in America, but globally, and I think small-scale agriculture cannot compete on price with farms employing industrial methods at scale, regardless of regulations. I think the modern food system is capable of producing and distributing more and cheaper calories than any conceivable local system; a single worker planting thousands of acres with a high-yielding monoculture will produce food at a lower cost than a dozen farmers working smaller plots of more varied crops.

Pencil-necked bureaucrats didn’t repossess farms and then start planting corn themselves; out of economic necessity the farmers themselves bought bigger tractors, which let one person work more land, so in the grain belt a single farm absorbed one of its neighbors, then another, and another, and so on up to the present day, with prime farmland an investment vehicle tenanted by 600-horsepower tractors. For the time being these still require drivers, but unlike self-driving cars, self-driving tractors will likely be a widespread reality within the next decade. Once these are out pulling sprayers and seed drills, it actually will be possible to grow corn from an office on Wall Street, with some on-site maintenance workers to keep the machines running. So perhaps the white collar workers will be the farmers in the end, even if they weren’t in the beginning.

Where I live the process was slightly different. My farm and the twenty-odd others up and down this stretch of the Wharton Creek valley used to milk cows as their primary source of revenue. None of them milk anymore, because the land is too hilly to aggregate into a single large entity. But the three thousand cow dairy on the flat bottom of a much larger valley fifteen minutes up the road is humming along, shipping out tanker trucks of milk every day. New York state produces more fluid milk than ever, but it now comes mostly from dairies with over five hundred cows rather than from family farms milking a hundred or less.

And it’s not just production. As Ted Genoways details in The Chain, over the course of the 20th century meat cutting moved from being a skilled job in which teams worked together to efficiently break down an animal to an unskilled, exploitative, and far cheaper system of industrial slaughter. Yes, USDA inspection requirements are unfair to on-farm and small processors, but the massive ones are also able to do the job for less money.

I could go down a long, perhaps endless, rabbit hole, looking in detail at crop yields, the percentage of the labor force involved in agriculture, the cost to get a cow butchered, and so on. I believe these data support my contention that the first cause of consolidation in the food system is the capacity to replace humans with technologies that can produce cheap food at scale. As agribusiness has grown its political influence has increased, a dynamic shared with oil companies, the tech industry, and all other sectors in which a few mammoth players have a lot of lobbying money to throw around. The malign political influence is downstream from the business model. Undoing that malign influence would provide a real but comparatively minor improvement.

Even if I’m wrong and Klar is right I see another problem with the political solution; who really cares about the quality or provenance of food? Sure, folks reading this site might, and there is a minority of the public that spends the time and money to grow produce or seek out good, local farms. But most people only really think about food when they can’t get it or when the grocery bill increases. A big reason we have the system we do is that the majority of the populace prefers cheap, convenient, processed food.

I wish there was a lively, public debate about all the facets of farming. I wish the personalities on Fox were bloviating about the merits and demerits of soil carbon sequestration, and I wish the personalities on MSNBC were bloviating about how to best compare the environmental impacts of extensive and intensive farming systems. I wish Joe Biden and Donald Trump began every speech by waxing eloquent (it’s hard, I know, but imagine it!) about how to balance the cost of dinner, food security, nutrition, and the health of rural communities, not out of a sense of genuine obligation, but because the voting public demanded it. I wish the culture war was about yogurt.

I do not expect to ever see such politics, which may be overly fatalistic. No doubt my resistance to Klar’s argument is skewed by my own preferences, at least in part. I see government as a diaper, useful for containing certain human excesses, but best kept at arm’s length lest the stink spread. While Klar views policy as an arena where workable solutions might exist and even become a source of optimism, I try to ignore it. But even this is not our greatest divergence over matters relating to localism and local-ish agriculture: Klar believes the current system is doomed, while I do not.

Here’s how he describes the situation:

A cursory examination of America’s industrial-agriculture predicament exposes the fragility of an unprecedented “bigness” in food production coupled with increasing dependency on the federal government. This is like a nightmarish, bureaucratic Andromeda Strain, and it will grow ever larger until it devours itself into oblivion, like a mighty dragon eating its own tail. (44)

And:

Yet no prophets are required to predict that if a nation abandons its local food production and becomes dependent on factory food transported huge distances using a fragile and vulnerable infrastructure, that sooner or later there will be a profound famine. (76)

And:

Industrial dependency (which also includes gigantic infusions of fossil fuels, herbicides, pesticides, and GMO seed) will become cost prohibitive, either before or after soils are depleted and waters are fouled. (91)

And:

None of the alternative energy technologies presently known can even remotely replace current human fossil fuel consumption—they all increase and accelerate pollution and energy consumption. (122)

While I am reasonably confident that technological advances rather than politics have been largely responsible for agricultural consolidation, I readily admit that my feelings about the future trajectory of the food system, let alone the nitty-gritty of solar power at scale, are just that — feelings. But my gut tells me that industrial farming isn’t going anywhere.

Events like the war in Ukraine and the pandemic lockdowns demonstrate the remarkable resilience of complex, global logistical chains. Things got a bit crazy, there were regional shortages, but neither of these seismic events caused widespread famine. By producing a huge excess of calories year after year, industrial agriculture has created a remarkable buffer against disruption.

And while industrial agriculture is wasteful, it is also quite resourceful. As soil degradation begins to impact yields, I expect cover cropping and perhaps even some amount of crop rotation, along with other soil building practices that are compatible with industrial farming, to become more widespread in the breadbasket. While Klar is correct that genetic modification of crops is almost always used to facilitate the use of herbicides, in principle it could also be used to rapidly create more drought-tolerant corn and soy. The industrial system will adapt, while remaining industrial.

And is this entirely bad? If you believe that the Green Revolution (the name given to the rapid advances in industrial farming methods that began in the mid twentieth century) was a con, a means of dispossessing local farmers, destroying local communities, and empowering Monsanto, with no benefits that couldn’t have been realized with more local solutions, then the end of the system it produced could only be for the good. But if you believe, as I do, that the glut of calories enabled by the Green Revolution really did prevent immense human suffering, that the methods it developed were and to a considerable extent remain necessary, it is hard to hope for its collapse.

Whether that collapse is inevitable sooner rather than later or if some form of the current system will continue to lurch along indefinitely has profound implications for the form the localist project should take. It’s worth repeating that the strength of Klar’s explicit proposals is that they are sensible, incremental improvements that should have broad appeal, regardless of where one lands on this question. But are they merely a first step, soon to be followed by many more as industrial agriculture implodes, or would they be a good but relatively minor piece of a much longer project of slow reformation?

Due to economic necessity, convenience, the ubiquity of foods engineered for palatability, cultural rootlessness, and so on, the industrial food system has broad buy-in, even if it’s usually implicit rather than conscious. If it is not doomed, if it is adaptable as well as extractive, then a better replacement can only come into existence slowly, as communities coalesce around fundamentally different relationships to food and the land it comes from. Rather than rebuilding from the rubble of the industrial food system, this would mean local food systems must persist on its periphery and offer an alternative to it, with hopes but no all-encompassing plans for the alternative to supplant the mainstream.

But as I say, these are my feelings glossed with just enough knowledge to make them persuasive, if only to myself. Klar describes a doomed agricultural system, one shaped primarily by politics, and thus correctable through straightforward mechanisms of policy. I gaze across the exact same landscape and see an ever more strongly entrenched food system, one based on the implacable logic of the market, one that can only change as human communities coalesce around different ways of living and eating. Perhaps time will reveal which of these hews closer to reality.

While we wait on answers to all that, Small Farm Republic is worth your time. A broadly unifying political movement centered on food and small farms may be somewhere between nascent and nonexistent at the moment, but such things must have a beginning. Klar puts forth an urgent and optimistic case for just such a movement, along with a practical policy blueprint for it to follow. If he succeeds in sparking it — if in the coming years real food is on more dinner tables and soil is on the ballot — based on what I’ve written here I will look foolish. I fervently hope I do.

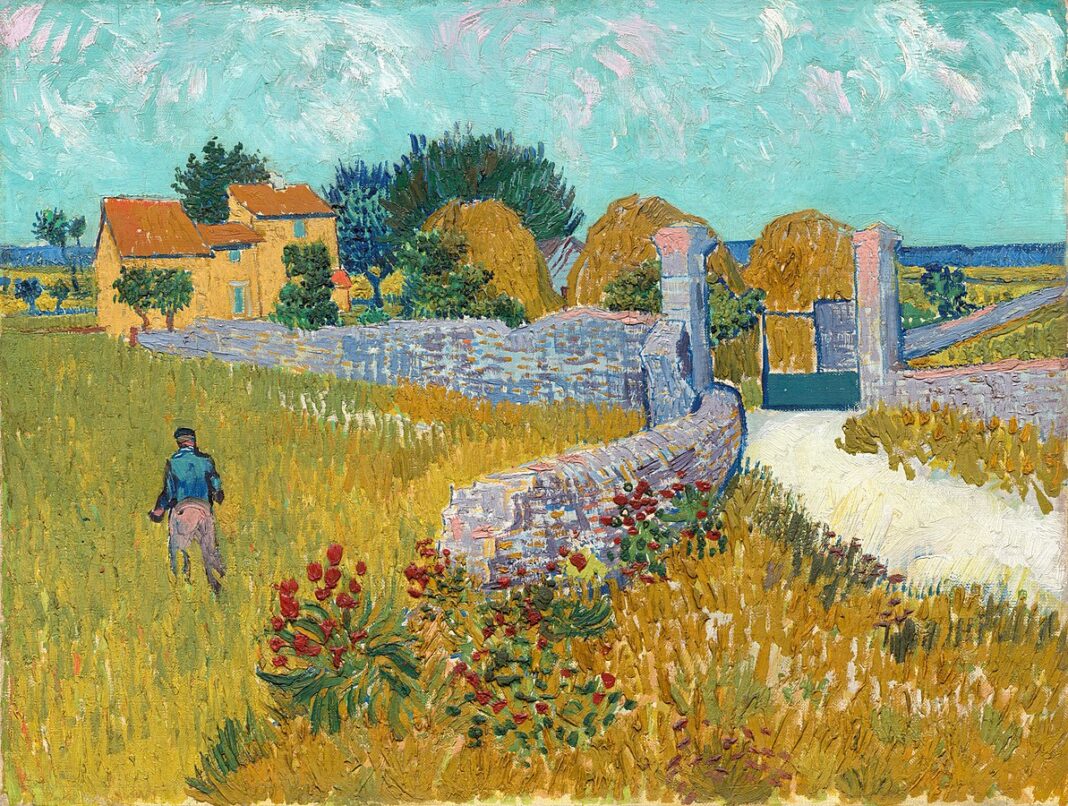

Image credit: “Small Farm in Provence” 1888 by Vincent van Gogh via Wikimedia Commons

This was fascinating.

Well, Garth, that was one of the most even-handed reviews I’ve seen all year, given that most at FPR are pretty balanced anyway. I agree with you about industrial agriculture, not because I like it or see it as invulnerable, but because it has basically proven Rev Malthus wrong. We have been feeding a geometrically increasing number of humans in the past 200 years.

However, I don’t agree with your starry-eyed praise of the Green Revolution, and John might be right if he is implying that small farms are more efficient — I think they are if you measure output per acre. I’ve seen plenty of small farms in East Asia, leading me to think that if knowledge and tools are available, more humans working per acre (or square mile) means more food productivity, though not if measured in dollar terms.

Vandana Shiva’s 1993 book Monocultures of the Mind unmasked a lot of the sly arithmetic justifying the Green Revolution as a miracle: shorter stalks mean a smaller denominator in the grain/chaff ratio, for example. A few years earlier, the Thai documentary Profits from Poison showed how pesticides initially drove off predatory insects, who then evolved with adaptive resistance and returned in droves.

I also disagree with your blithe claim that lockedowns did not cause “widespread famine”. I’m not sure what a non-widespread famine would be, but this article about The Gambia reports persistent hardship: https://unherd.com/2023/07/western-lockdowns-still-torment-africa/

Thanks, Martin.

It’s definitely important to distinguish calories and economic value when talking about yield per acre. I don’t doubt that in some production systems more hands working the land can yield more of either or both. But I maintain that if we are measuring the former the techniques of the green revolution must be employed; heirloom corn, no matter how lovingly tended, is not going to compete with modern hybrids on yield. Heirloom potatoes might, but potato based food economies bring other difficulties.

Of course, there are endless ways we could try to account for externalities: hybrid corn requires more fertilizer inputs; when we talk about an organic system do we mean a truly closed one, or are we allowing synthetic nitrogen to sneak in via chicken manure; how do we account for various forms of much more land extensive but low impact pastoralism, and so on. But when I compare global population growth with the dramatic decrease in famine since 1960 I have a hard time talking myself into any explanation besides the cheapening of food enabled by the technologies of the Green Revolution.

A great book on all this is “Meat: A Benign Extravagance” by Simon Fairlie. Among other interesting things, in it he lays out several different schemes for feeding the UK in some detail, ranging from the status quo to an entirely closed organic food system. Along those lines, I can envision lots of other systems that I think would be better than what we have and that could in theory feed the world, but I think the fact that the current one, for all its problems, is currently doing just that in reality and that this has not been the norm for much of recorded history, should be acknowledged, and that changes to it should thus be made incrementally, with caution and humility.

On your second point, I initially had an even more emphatic statement – I believe adding the qualifier “widespread” was an editorial suggestion. I stand by it, though our disagreement may be a matter of semantics or the result of a lack of clarity on my part. My argument is that despite chip shortages affecting farm machinery, expensive and not always available fertilizer, a lack of spare parts, and everything else that came with supply chain disruptions and the war in Ukraine, the industrial food system nevertheless generated its usual massive excess of calories every year since 2019. I would ascribe famines in Gambia and suffering in Covid Zero Shanghai to horrible political choices. This makes them no less horrific for the people suffering as a result, but not, to my mind, the result of an agricultural system in failure.

If the modern agricultural system does rapidly collapse at any point I would expect famines on a scale unprecedented in human history to result, an idea I find rather troubling. So perhaps my belief in the status quo is in part hope born of willful myopia.

Thanks for a thoughtful reply, Garth. Having read Brian’s comment (below) after your explanation of lockdown destruction and war devastation, I’m inclined to suggest that a large part of the Green Revolution success was also due to “political choices” rather than the magic of GMO, fertilizers, and insecticides. Generally, though, I agree that the “system” should change slowly — but steadily — and the protesting farmers in Netherlands illustrate what happens when it doesn’t.

I think that is our fundamental disagreement. I see the technologies being adopted across a wide range of political systems. As a rule, farmers want to produce more by increasing yields, labor efficiency, or both, regardless of where they are.

More fundamentally, as I said in my previous comment, the Green Revolution actually did radically reduce the incidence of famine in the world as it was/is. I can imagine alternative ways the food system could have been developed in step with various political reforms, leading to a less industrial agriculture that nevertheless could meet the world’s needs, but in my view they would have required unrealistic political and social revolutions to actually be implemented.

Of course food production and distribution are bound up in the political process. I just think that the green revolution made food incredibly cheap, which in turn made it easier for even the most corrupt and feckless of governments to feed its populace, or at least to be more able to do so.

“the protesting farmers in Netherlands illustrate what happens when it doesn’t.”

The Netherlands farmers are protesting because the government is going to steal their land.

“as farmers who once dominated the nation’s countryside (and legislatures) were pushed out by ambitious, urban, white-collar ‘experts,’ ever-larger corporate actors have been able to manipulate tax laws, regulations, and subsidies to eradicate those small farms for the expansion of large-scale agricultural (and chemical industrial) interests.”

It seems like you’re focusing nearly entirely on the first part of the sentence, and not the second. Yes, economies of scale are of course undeniable, but how much influence has the regulatory state had? You seem to think it’s not just secondary, but trivial. Others think it’s far more important, which doesn’t require denying all the forces you talk about. How about we run the experiment of demolishing all these regulatory issues that benefit big interests, whether intentionally or not, and see what happens?

“I see government as a diaper, useful for containing certain human excesses, but best kept at arm’s length lest the stink spread.”

Well, that’s a lovely sentiment, but the problem is that government has been spreading its filth over everything for nearly a century now. Using it for our benefit seems a completely reasonable thing to do at this point. Do We the People want to live like this? Honestly, I think We do, certainly in the current political reality where urban interests have all the power and rural interests have already been completely destroyed. But the alternative is still worth fighting for.

Urban-rural tension has existed as long as cities have. Consolidation of power in a dense area is augmented by easier networking, an advantage which the internet has reduced, leveling the playing field somewhat.

In recent years, I have come to believe that it won’t end well when most of the populace shows disdain for the people who grow our food, sew our clothing, and build our houses.

“Urban-rural tension has existed as long as cities have”

Yes, but at the risk of repeating what I’ve said a billion times before, the “one person one vote” atrocity destroyed what had been the brilliant American solution of preserving power for rural areas, and it’s no coincidence that they immediately collapsed economically, demographically, etc.

In both the U.S. and England the mass movement of farmers off the land via the expansion of industrial farming preceded the Green Revolution. And it seems to have occurred similarly in other parts of the world as well. Since it’s quite evident that the expansion of industrial farming had as much to do with politics as it did to do with economics, it would seem that the Green Revolution was kick-started by earlier politico-economic decisions that privileged what we now call Big Agra, which requires the mentioned technologies.

There’s no doubt that the Green Revolution/Big Agra did a lot of good in the short run, in terms of feeding people, preventing famine, etc. But a lot of damage has been done as well, including the not-insignificant fact that it has made food production almost entirely dependent on the petrochemical industry. If one looks at Monsanto as a sort of microcosm of this dynamic, doesn’t it seem that while we can praise them for their efforts in increasing productivity, there are lots of other things which dampen that enthusiasm a bit?

I would argue that the Green Revolution, and the governmental involvement that supported it, should never have happened in the first place, simply based on the structural theft required to maintain it. But like any addict, we are dependent now, and there’s simply no easy way out, even if – as I believe – it’s required.

The bottom line here is that our hearts have to change. The old fashioned word here is repentance! And while this will have implications for political action, it must start with people who know something is wrong, take responsibility for their part in it, and take action on the individual and family scale to begin making needed changes.

I’m beginning to see this in the Homesteading movement, almost literally a grassroots endeavour that may be the start we need.

Time will tell. In the meantime, the book sounds like a must-read!

Hi Garth;

I’ll add one variable that has not been emphasized in your review or the comments enough. That is fossil fuels as the essential enabler of industrial ag. Politics, culture, economics, all are underwritten by the ability of fossil fuels to reduce cost and labor.

Humans are in temporary overshoot beyond the natural carrying capacity of the biosphere based on the Haber-Bosch process and diesel powered equipment. The timeline and tipping points are uncertain, but return to a sustainable equilibrium is inevitable as fossil fuels begin their slow decline.

That small farms and the resettlement of America ( and the other “developed” countries) will occur is certain. Under what political and economic arrangements is the real question on whether we can hang on to a republic through the difficult transition ahead.

If you haven’t already, I suggest you read and review the book by Chris Smaje “A Small Farm Future”, which explores this space.

Comments are closed.