“The Kind of People We Need at the End of the World.” Elizabeth Oldfield shares her family’s journey into communal living and relates how the humble, daily acts of prayer and cooking and gardening form her response to the forces of despair: “I am gardening because I feel anxious about the future, about the oncoming climate catastrophes, about what AI will mean. I want my hands in the soil because I need to find a way to be of use. I need to steady myself, pay attention to the local at the level of moss and aphids and what is happening with my first ever kale seedlings. The growing of food is the most elemental of activities, and I want to learn it. I need to know what my ancestors knew, but which my generation, fed on the plastic-wrapped, air-freighted outputs of industrial farming, has forgotten.”

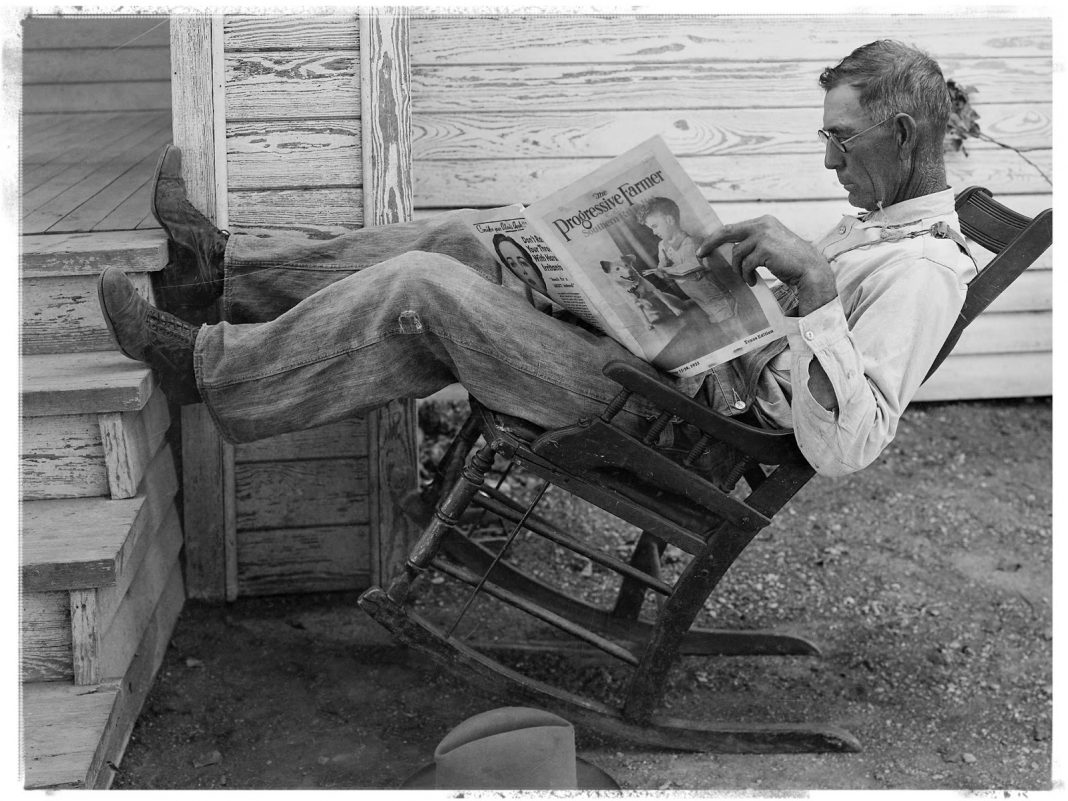

“Rewilding: A Glimpse Into Regenerative Agriculture in the US.” Indra Shekhar Singh finds common bonds between Indian and American farmers who care about the health of the land and all its members: “More than we would like to believe, Indian and American ecological farmers share a part of their souls and a vision for a sustainable Earth. We only have to try and connect the dots. And if our countries are to be friends in real-time, our foreign relations must include our farmers.” (Recommended by Nadya Williams.)

“Friday Night Lights: Family-friendly Football Done Right in Latrobe.” At a Steelers’ Friday Night Lights practice, Will Bardenwerper finds that even NFL football can foster community and family: “This night in Latrobe hearkened back to what football — even professional football — used to be, authentic and accessible, before it morphed into the technologically sophisticated, corporate-driven, multibillion-dollar entertainment product that is the NFL today.”

“The Death of Church and Pub.” Carl Trueman mourns the decline of community-building institutions in the village where he grew up in England: “And the sad fact is that pubs and churches are not being replaced by something that fulfills the same function of shaping community. There is no need, it seems, since that function has itself more or less vanished. When communal space disappears, communal bonds disappear too.”

“Made in Farmville.” Bradley Devlin visits Farmville, Virginia to learn about the place Oliver Anthony—author of the viral hit “Rich Men North of Richmond”—lives. While the first question at the Republican presidential debate involved Anthony’s song, the artist was playing at a local venue and talking with folks unconcerned with the politicians posturing for their votes: “Farmville resident’s political beliefs vary widely. . . . But everyone agrees that Democrats aren’t coming to save Farmville, and neither are the Republicans. . . . Oliver Anthony has no idea what was happening in Milwaukee. Nor did North Street Press Club. If they knew, they either wouldn’t care, or possibly would have flipped the TV the bird.”

“Who Would be a Farmer’s Wife?” Juliet Nicolson praises Helen Rebanks’s new book: “The challenges inherent in life on a farm, inside and out, never diminish. Rebanks is always conscious of the gossamer thread linking life and death which might suddenly fray or snap through miscarriage, old age, a killer virus decimating the cattle, a violent snowstorm endangering the sheep or the final illness of a beloved dog. The blood, mud, slog, exhaustion, bureaucracy, financial angst, challenges of sustainability, the role of the consumer and the concerns of animal welfare are ever-present. At the same time, her love for her family and her quiet self-assertion act as ballast.”

“America has the World’s Safest Air Travel but Sucks so Bad at Car Safety.” Marina Bolotnikova tries to account for America’s remarkably dangerous roads: “Of course, individuals making unsafe choices — speeding, say, or driving drunk — matters. But these are distractions from what makes the American system of driving so unsafe in the first place: we have a proliferation of fundamentally unsafe roads, known among traffic safety advocates as “stroads,” that combine wide lanes and speeds higher than 25 miles per hour with frequent turns, stops at traffic lights, and shared traffic with cars, pedestrians, and bikes. With all these conflict points, it’s inevitable that collisions will happen.”

“Does Sam Altman Know What He’s Creating?” The answer that Ross Andersen arrives at, in this lengthy essay for the Atlantic, is “no.” And as FPR has been saying since its founding, too big to fail is simply too big. As Anderson concludes, “No single person, or single company, or cluster of companies residing in a particular California valley, should steer the kind of forces that Altman is imagining summoning.”

“Behind the AI boom, an Army of Overseas Workers in ‘Digital Sweatshops.’” Rebecca Tan and Regine Cabato detail the effects of AI gig-work in the Philippines: “More than 2 million people in the Philippines perform this type of ‘crowdwork,’ according to informal government estimates, as part of AI’s vast underbelly. While AI is often thought of as human-free machine learning, the technology actually relies on the labor-intensive efforts of a workforce spread across much of the Global South and often subject to exploitation. . . . Scale AI has paid workers at extremely low rates, routinely delayed or withheld payments and provided few channels for workers to seek recourse.”

“In Amish Country, Buggy Lanes Will Flank Some Rural Roads.” Lonnie Lee Hood highlights counties in Tennessee and Ohio that are adding buggy lanes to busy roads: “Amish communities are among the fastest-growing population groups in the United States, and their use of horse and buggies has created an infrastructure problem in some rural areas. In Lawrenceburg, for example, the Tennessee Department of Transportation (TDOT) is currently constructing a buggy lane exclusively for Amish use following a number of buggy-related accidents and ongoing safety issues.”

“Learning to Love Grass.” Alex Rowson describes the glories and fragility of Britain’s meadows: “As meadows are manmade and man-maintained habitats – requiring the right timing and amount of grazing, a yearly cut, and an organic approach to management – their preservation can be challenging, for both old and new landowners. They are also highly susceptible to neglect, quickly swamped by coarse grasses, weeds, scrub, and, eventually, woodland. But it is ignorance of their biological value that is arguably the real killer.”