The sunlight softens the space between as grass and dandelion join. My daughter, lips pursed, blows the seeds, linking her to children across time. The world contracts as she inhales; expands as she blows. It laughs with her when the puff explodes into fairies in the half-light along the bank.

We’re upstream from the farm, passing time during my son’s soccer practice. The field is sandwiched, stuck in between. Off to the west, the creek throws itself against childhood lessons that water only moves south to the equator. Ozark waters don’t mind universal laws; the Muddy Fork wanders north. North and east of the creek sit rows and rows of houses. They’re treeless, nothing distinguishing them from any place. Looming behind me, a stone’s throw from the creek’s temperamental current, is the town’s sewage plant. Beyond the tanks of shit another farm has fallen, streets sprouting where cattle once grazed. Machines move across the rolling land rearranging the world for the upwardly mobile.

My daughter doesn’t know any of this. All she knows is the moment of release; sun’s illumination on the puff of fuzz as seeds scatter.

The creek we walked along is fed by springs and rain—and the sewage discharge. It’s all treated and likely cleaner than the city taps. We live downstream and never think of the disaster quietly waiting. Our children play in the creek’s riffles, chasing crawdads and turtles from spring to fall, oblivious.

We never seem to fully know our place’s fragility. The earth and waters below us mingle freely, carrying humanity’s woes through dark limestone chambers, releasing them to the sunshine without warning. Trash floats and sinks. It’s visible, flagrant. Sewage and fertilizers and herbicides, though, are silent and unseen.

The Muddy Fork, like all tributaries, is part of a larger story. It begins life away on the southern slopes of Stevenson Mountain near Hogeye. From there it flows to the Illinois River, joining it north of my farm. The Illinois itself starts near the Muddy Fork—an accident of geology made one river and one tributary. The Illinois, wider now, loops north and west across county lines—defying my school lessons—then south through Oklahoma, passing through an impoundment before ending its 140-mile trip in the Arkansas River. Its waters reenter the Natural State at Fort Smith, pushing between the mountains that have defined my family since before the Civil War. The Illinois, held in the arms of the Arkansas, meets the Mississippi near that other great Ozark river, the White, and then the ghosts of my people flow into the world.

If anybody knows the Illinois it’s because of two things. Where the Red Fern Grows, the saddest story about coon dogs ever written, takes place along its Oklahoma banks. And there’s the multiyear, multimillion dollar lawsuit between Oklahoma and Arkansas as agriculture and thoughtless growth have dumped untold pollutants into the river. More than a little money has been spent on this fight. A person doesn’t bring it up in certain circles. Some see no issue with how the watershed is managed. Others argue this is the cost of pushing growth over community—and it’s too high.

The fight around the waters of my home and the dandelion my daughter picked are two sides of the same coin. The puff and release are known to us all—dandelions are often the first and last glimpses of color in the year. They’re durable and do many things for us beyond providing a blue-eyed child with giggles.

Newcomers, if like the humble dandelion, can give valuable lessons on living in peace with what came before. In my home the rivers and land are battered by demands for profit and progress. They fight back as they can. The Illinois and its tributary over the decades have lost fish and birds and clarity. Progress in the region pushes more and more runoff into the watershed. The land has been overworked, and it sheds fertilizers and herbicides like a spreading cancer. The hills have raged in response to the danger from all sides, and the river is taking land it once gave, sending it downstream.

Like the little yellow flowers, our river is beautiful and durable, despite the damage we’re doing. These waters are native to the mountains and representative of us. They’re clear and strong; gentle and inviting. They’re also muddy, roiling, and angry. The waters have watched as we have moved through the hills for centuries. They’ve fought back as humans have pushed them beyond their natural inclinations. I don’t know if a river dreams, but if so, I doubt the Illinois dreamed of this world.

But always there are spaces the river harms less. And those spaces have dandelions.

Dandelions shouldn’t be here.

Most folks don’t realize that. If they do, it’s likely thanks to lawncare aspirations fueled by Instagram and white New Balances. But really: dandelions are immigrants descended from forced migration. Scholars aren’t sure when they showed up first. Perhaps with Vikings, but the likelier story is that Pilgrims brought them. That rings hollow to me though. The little flower is too bright and spontaneous for dour Calvinists.

These days invasive species in my home are once again in a spiral of negative attention. As usual, the dandelion is ignored, except by children seeing the world as the universe intended. Perhaps its humility—despite its profligacy—is the flower’s secret, but I doubt that. I think it’s because the dandelion holds itself in community with us.

Its place in human life mirrors its position in the ecosystem. Dandelions can be food, medicine, and drink. Scientists wonder if they can become a substitute for rubber trees. Their lengthy taproot looks like a wobbly carrot.

That taproot is why I like the dandelion. Those roots, if you’re interested in staying the same, are not for you. Taproots break up hard soil, letting air and water deep down into the earth. Life into the darkness. And these carrot imposters do even more. Taproots bring up into the top layers of soil all sorts of stuff that’s locked below. Minerals and nutrients hidden by years of bad decisions and stagnancy emerge. A taproot allows good things to become better. They break old forms and invigorate them with new energy, allowing us to cast off old ways of knowing, keeping only the neighborly parts and discarding the rest.

The outside world provides lessons we desperately need if we’re to remake this place. It offers examples of what happens if we don’t. It shows the simple things we need if we’re humble enough to see the magic in a dandelion puff. Or the direction its roots point.

It was hot. Makes sense—it was late July. A hard rain had scoured the road out of the landing, turning the river from emerald and sapphire to molten rock and roiling dirt. The high water lingered, the air thick enough that breathing felt like drowning. As I climbed out of the valley, bouncing and rattling across the road, I headed north and east, tires flinging stones to Lucinda Williams. Half an hour later I pulled off the forest road, truck squeezed between oaks and boulders. I got out and stood. Heat from the engine rose in waves as my body condensated in the wet air. Mud and poison ivy sucked at my feet. I found the trail and tucked off along the cliff band. Honeysuckle and brambles clung to my arms and legs, leaving sweetness and pain behind. After a bit, I found the gaping hole in the mountainside, a black void in the mass of wet life. I wriggled in and faced the dark, looking at a world only roots know.

Also. I hate caves.

I like the feel of air across my skin, sunlight searing my eyelids, and the knowledge that the world is not about to crash in upon me. Caves, especially ones with small openings, are not my idea of fun. Light only comes if you bring it, and I have no desire to play the role of Prometheus. The interior life of the hills here is a private thing, at least to me. We leave our legends and our dead here, cracking open the earth to consider the deposits infrequently. Sinners hide in the memory of the underlands; Jesse James playing Hades with a six-shooter and cowboy hat.

These days caves tell the story of change in my home differently than the loss of farms might. The underworld holds our water; keeping it in times of drouth, almost as if it were protecting a thing we squander. Every cave I’ve been to in the hill country has water in it.

The water talks. All water tells stories, and Ozark waters are no different. The easy story is of beauty. And boy do we have it here. People don’t realize this, but the tallest waterfall between the Appalachians and the Rockies is here in the Ozarks. The falls at Hemmed-In Hollow, by the Buffalo National River, drop some 200 feet, spilling through the holler head to the delight of thousands every year. Even when it’s dry and the falls are only memory, the trickle of water over the lip of the rock is mesmerizing, Zen music in the heart of hillbilly country.

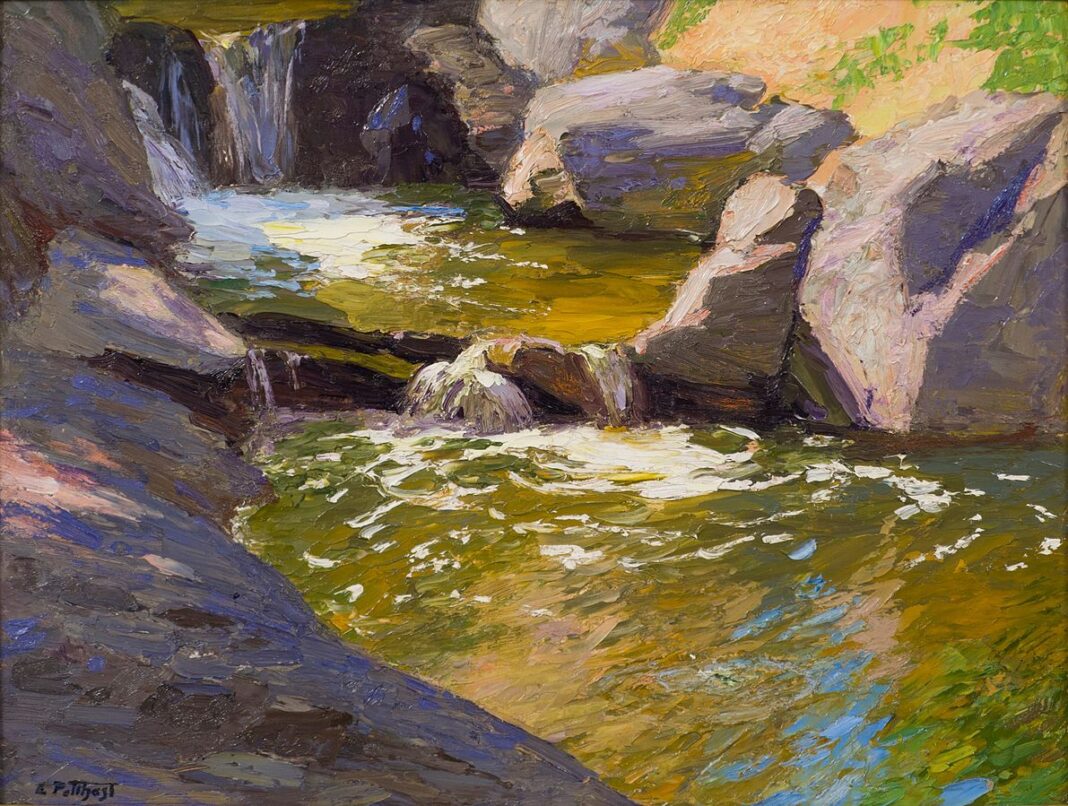

The best falls are when water just appears, a sudden gift, before rolling down a low series of stone. It never “falls” but stays locked to the mountainside its whole life. You stumble on them. They only appear when there’s too much water in the world that day. You need patience to see them, and a bit of courage.

Our farm has falls like this. They don’t rush around and make a lot of noise. When the rain is high the hollers and springs fill; the tight, sycamore-anchored stones run with murmurs. Occasionally a flash of light shows as the whisper turns to a chuckle and a pool appears, quickly, before it realizes it’s in the open and dives into the rocks on its way to the Muddy Fork.

Beauty—flashy or quiet—isn’t the whole story. Our waters speak of other things. Since the 1970s folks have asked questions about what’s in our water, and how and why it got there. Of increasing concern for the waters is runoff, both urban and agricultural, and its influence on life in the hills. Since the ‘70s specialists in the lawsuit between my state and Oklahoma have measured the river’s angry outbursts. They track feet lost per year per farm, pollution levels in the river—all fuel for a fight about responsibility. It’s a fight that’s hard to see the end of when the powers that be dismiss what’s inconvenient.

This is visible. But most of the work done in my place, good or bad, is not. To see it, you must go where the roots point. There, where the place’s veins open before you, waters running their course through the broken bones of my world keep record of the labor.

Everything we do, seen or not, runs off. That’s really why I like the little dandelions and why I hate caves. To me, the caves hide problems. All our sins end up in the earth’s blood, gnawing away with a patience and strength that is terrifying when you stop and consider it.

But that little flower, that little yellow bloom that seems so fragile with its fairy promises, takes the sins of my people and tries to make them right. It anchors the world we stand on, nourishes it. It will feed our souls if we can stop killing it. And on a hot afternoon it gives a little girl something to laugh at as she spreads the seeds of promise.

Lovely reflections. Did anyone ever seriously teach “water only moves south to the equator”? Why? Because south is downhill???

Maybe it was someone who knew the Mississippi basin well and nothing else (e.g., Nile flows north, Columbia flows west)? Or maybe just sloppy geology, confusing the more accurate imagery of “water ends up in the seas” with compass directions?

Comments are closed.