There are a few words that have experienced unprecedented levels of usage since the year 2020. “Mask.” “Corona.” “Unprecedented.” But one still sets my heart a little akilter when I hear it, despite it becoming as common as the common cold used to be, and that is “activism.” For me, it conjures up images of restless crowds, smashed windows, signs with jagged words in angry red paint. I tell myself that I want nothing to do with activism.

But the human heart is a funny thing. Because even as I cringe at the term, I find myself awake at night hurting for the homeless and victimized and hungry. I rage at the injustices of war and racism and prejudice. My moods can instantly morph from general content to bubbling cauldron of incendiary emotion at the news of a shooting or bombing or flood or tsunami. When I look for the answer to my question, “What can I do?” I’m left with an inconvenient answer.

Activism.

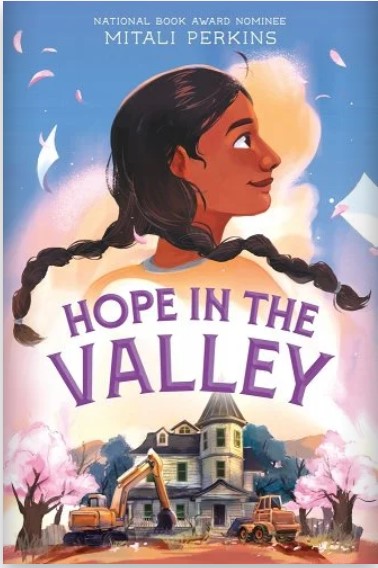

National Book Award finalist Mitali Perkins has become one of my “automatic read” authors since I first encountered her heart both for classics and for fostering conversations and understanding in her 2021 non-fiction title, Steeped in Stories. But when I read the description of her newest middle-grade novel, Hope in the Valley, I wasn’t immediately hooked. School Library Journal’s starred review concluded: “Perkins explores topics that were relevant both then and now, including racism, housing inequity, and activism.” There was that uncomfortable word again: “activism.”

If it wasn’t Mitali Perkins, I might not have picked it up. Yet I was immediately drawn into the story of Pandita Paul, a twelve-year-old Indian American whose grief at the recent loss of her mother is compounded by the prospect of the destruction of her mother’s favorite place: the beautiful, abandoned house and orchard across the street from their home. Almost against her will, Pandita is pulled right into the middle of a developing controversy: the activists at the historical society want the house to be preserved; the activists fighting for affordable housing for underprivileged residents of Silicon Valley want the land to be developed.

Pandita is soft-spoken and introverted, especially since her mother’s death. Yet she joins ranks with one group of activists and then the other—first with the historical society, volunteering to read through the letters and documents left in the house, in search of some nugget of historical significance that will save the house. When the disrepair of house and orchard prove an insurmountable obstacle to overcome, Pandita switches gears. With the house demolished, the affordable housing proponents have a new battle to fight: with the developer who wants to turn the land to another money-making complex. Everything she’s learned about the house’s previous owner convinces Pandita that this woman from the home’s past would choose to help the misunderstood and underprivileged rather than go with the accepted money-making strategy. But in order to make this happen, Pandita has to overcome her shyness and aversion to conflict. She needs to make her voice, and the house’s story, heard.

From the first few pages of Pandita’s story, I was reminded of a favorite book of mine: Emily of Deep Valley, by Maud Hart Lovelace of Betsy-Tacy fame. I happen to know it’s a favorite I share with Mitali Perkins, and I’m sure it was not coincidental that so much of Pandita’s story echoes the growth of the title character in Lovelace’s story. Emily, too, struggles with sadness and loss. She needs to find her purpose in the world, and more importantly, she needs to find herself. Yet as so many of us have in the truly pivotal moments in life, she finds herself by losing herself, by standing up for those around her who are suffering. In Emily’s case, she becomes aware of the prejudice in her community against the local Syrian immigrants, and she steps up to right that wrong—not through protests and angry altercations, but by starting with herself. She forms friendships. She fosters communication. She builds community. She makes bridges. And ultimately, though the story does end with her Syrian neighbors living a little more comfortably, the biggest change that Emily made was in her own heart and in her own actions.

Mitali Perkins reminds us, through the story of Pandita Paul, that we have to start with ourselves if we want to change our communities. Activism needs to begin by fearlessly staring down our own prejudices, by rooting out the injustices we allow. Once that is accomplished, we can turn to the outer world—but even then we should begin with thoughtful conversations, efforts to listen, and acknowledgment that refusal to see the other side of things will only build up bigger and stronger barriers.

Mitali Perkins, in Hope in the Valley, sat me down for a gentle, needed conversation about my own blind spots. She reminded me that activism is a necessary tool for justice. That it is no less active when it means a chat on a front porch with an elderly neighbor or the courage to speak up over dinner with our family. Most of all, she helped me realize that the most essential activity for justice should be the necessary, painful, grace-filled movement of the heart.

Image credit: Konštantín Bauer, Refugees (1927)

If you like that, here’s a good one:

https://www.amazon.com/Little-Pink-House-Defiance-Courage/dp/0446508624

Not a novel, actually a true story. Pfizer is a bad guy, which those of us older than 4 will understand but those whose memory is shorter might be confused by. Unfortunately the other bad guys are Democrat politicians and progressive judges, and the protagonist isn’t a fictional immigrant girl but a lower middle class white woman, so of course it has nothing to do with injustice, prejudice, community destruction, etc. Oh well.

Comments are closed.