Many years ago, I lived in a contemplative monastery. As part of the formation program, one of the priests in the monastery gave the students an overview of canon law. Knowing that his students likely knew only American concepts of law, he framed his introduction with a remark I never forgot: “You must understand that in the classical Roman conception of law, there is really no need to think of rights. Only duties.” I never studied canon law beyond that introduction, so I cannot confirm whether that is indeed the way to understand canon law. But the concept stuck.

Modern Americans, both on the right and the left, tend to speak and feel quite strongly about rights. Americans on the right are adamant about their rights, especially those “God-given rights” enshrined in the Constitution: free speech, the right to bear arms, etc. Those on the left have an expansive view of rights that now encompasses everything from the sacred “right” to abort one’s own child to the “right” to demand others call one whatever name or pronoun one decides he identifies as that day.

While the ever-evolving notions of rights championed by progressives are a far cry from the Bill of Rights to which conservatives hold fast, the focus on rights itself stems from a debilitating individualism prominent on both right and left. Conservatives would do well to reframe their understanding of rights, to reclaim the classical emphasis on duties, thus putting rights in their proper place.

Erika Bachiochi recently wrote an excellent essay on a proper natural law understanding of rights. Bachiochi starts by laying out the two very different accounts of what rights are and from where they come. The first, the early modern account, views rights as “protections for individual autonomy, or in Mill’s telling, individuality. This account arises out of a view of the human person as one who is naturally self-sufficient and independent—who, of his own free will, in Locke’s telling, enters into civil society to protect himself and his property.” If this is what man is—an independent, self-sufficient creature who possesses rights merely in order to be left alone in his autonomy, then man is not “a civic or political being, necessarily dependent upon and in community with others.”

The classical law understanding of rights, grounded in the natural law, is quite different: “natural law summons, enjoins and defines natural duties: the good human beings ought to do and the harm to be avoided . . . Contra the early moderns, rights don’t come first; properly understood, they are intrinsically knit together with duties. Indeed, the pre-moderns had only one word for both: ius (the root of ‘justice’ or what is owed).” This is quite a different rights framework from the modern understanding. Rights are not primarily about freedom from something—freedom from government coercion, from the actions of others, from restrictions in general—but are about freedom for something. Rights exist to preserve man’s ability to carry out his duties.

As Bachiochi rightly points out, despite the Enlightenment-era origins of America, an authentic American understanding of rights does not need to be grounded in the modern conception of autonomy and individualism: “at the Founding and for much of American history, both republicanism and the Christian faith provided important communitarian counterbalances” to liberal individualism. Yet if one consumes modern conservative media, it is fairly obvious that the modern theory of rights grounded in individualism, in freedom from constraints, rules the day. Rights are about my right to speech, to guns, to privacy. They are about my right to do what I please without government interference. Why? Because it’s my right, that’s why. And that is hardly a compelling justification for rights.

Legal scholars have been highlighting the errors of the modern individualist notion of rights for quite some time; the argument for the proper reframing of the theory of rights is not novel. Bachiochi uses the classical understanding of the link between communal duties and rights to reframe talk about women’s rights. Hadley Arkes has written for years about the proper understanding of natural rights and how it clearly demands that the unborn child in the womb be protected from abortion.

The proper framing of rights is not mere academic banter. The liberal framing does not match reality and this false theory has real-world consequences. Men are not by nature individual and self-sufficient, entering into community only to protect their property. Men are by nature communitarian: every person comes into being as part of a family, a community, a society. The whole idea of being born into a state of nature as a pure, autonomous individual and then choosing to enter a governed society is an unproven myth; to my knowledge this has never been the way man has lived. And if that concept of man’s nature is wrong, an explanation of rights based on that false individualism is likewise wrong. Conservatives need to recover (or perhaps discover for the first time) a more traditional way of understanding what rights are, where they come from, and what they are for.

Perhaps conservatives—without in any way diminishing their love for and devotion to the rights contained in the Constitution—would do well to reflect on what rights are and how they view them. Rather than fixating on the right to be free from government intrusion or free to speak, act, worship, etc. for the sake of freedom itself, Americans should reorient their understanding of rights as protections meant to facilitate the accomplishment of their God-given duties.

The First Amendment protects the free exercise of religion because one has a duty to worship God. It protects the freedom of speech because one has a duty to speak what is true and good without being coerced or silenced. The Second Amendment protects the right to bear arms because citizens have a duty to protect the innocent from violence. The Fourth Amendment protects against unreasonable searches and seizures because the government has a duty to protect the safety of its citizens and their homes from unreasonable intrusion. The list goes on: consider a right, and it should not be hard to find a legitimate duty that right exists to protect.

Rights are not about me and my freedom to do what I want, because freedom is a means to do what is good, not an end in itself. Focusing on duties can help refocus citizens on the purpose of freedom, the purpose of government, the purpose of life itself. Life is about duty: duty to God, duty to one’s family, community and nation, duty to act for the common good. Our duty is to live lives that conform to what is good, true, and beautiful. Natural rights in general, and the rights enshrined in the Constitution in particular, are means for citizens to fulfill their duties, live good lives, and build up their families and communities.

A proper shift in thinking about rights and duties will help conservatives appreciate the purpose of rights as means rather than ends. It will also serve as a firm foundation from which to oppose the false “rights” invented and claimed by the modern left. If someone claims a right and it proves difficult to find a corresponding duty or good that it protects—if there is no reason for the “right” other than freedom for its own sake—we should be on guard.

Rights exist to preserve the freedom to fulfill one’s duties, to do what is good. They do not exist to give people more individual freedom for the sake of individual freedom. Conservatives should preserve this classical idea of rights. It is much easier to love and defend our rights if we understand why we ought to have them in the first place.

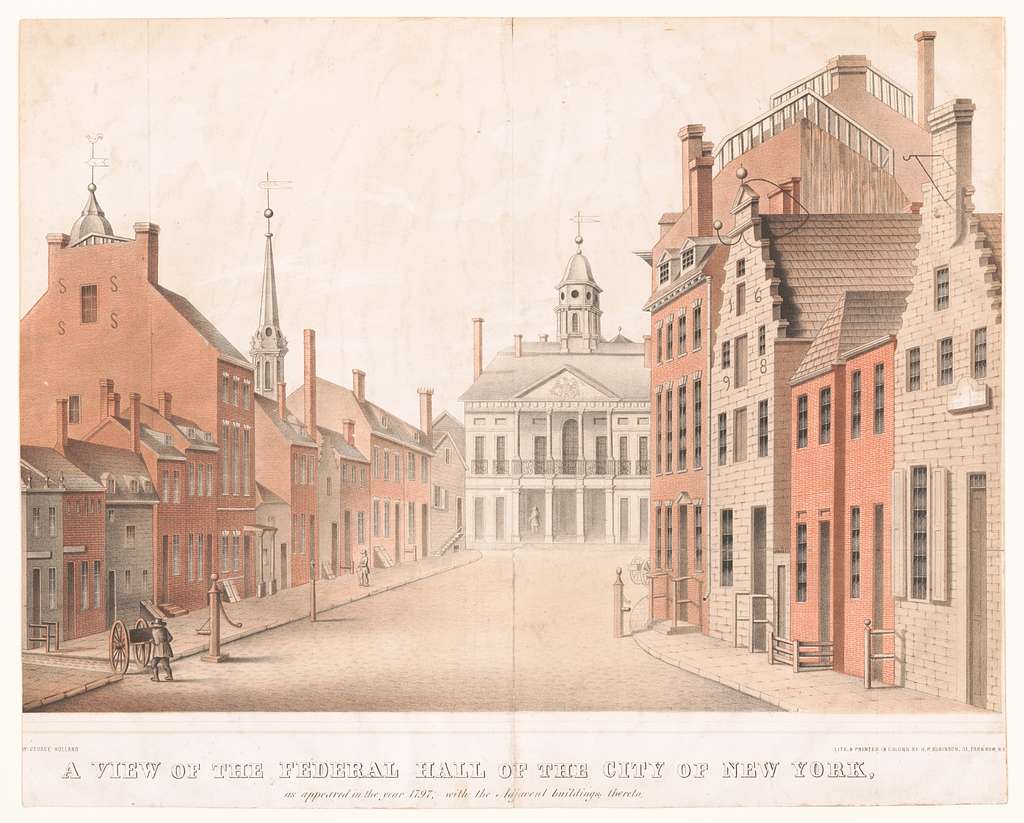

Image via Picryl