Boise, ID. I spent most of my life oblivious to how architecture influenced my mood, my perspective, my sense of self. I knew, as I think most people do, which places felt better to me than others. I also experienced and recognized a sense of longing—a longing that at times might have drifted into a sort of envy—when I saw a beautiful building, walked down a beautiful street, or imagined my life in a beautiful home. I formed strong opinions about the best neighborhoods to live in, the best configuration of furniture for my home, the best church to worship in, the best restaurants for various kinds of meals, and the best classroom set up for different kinds of teaching.

In this I developed a feeling for good architecture that was deeply intertwined with my feeling for the good life. However, this feeling was mostly inarticulate and was not well-incorporated into my sense of self, nor into a coherent philosophy of life. I knew some of what I liked, but I did not know why I liked it and I was not very good at predicting what else I might like or want. Likewise, I often had difficulty determining if I needed to change myself or my environment. This, of course, is one of the central questions of life: am I wrong or is the world wrong? Do I have poor taste or is this poorly designed? Am I uncomfortable because of my physical, mental, or moral weakness? Or am I uncomfortable because this chair or this sweater or this job is poorly designed, broken, poisonous?

A few years ago, my husband picked up a copy of Christopher Alexander’s A Pattern Language on one of our many trips to Powell’s City of Books in Portland, Oregon. It sat on his shelf for a while and he browsed around in it, telling me about various design principles as he read of them. The ideas he repeated were profound, surprising, and intriguing and so I picked it up and read straight through its one thousand pages and 253 patterns in a few days. I have not been the same since. I still wrestle with these central questions in many and various contexts, but Alexander has given me both a vocabulary and a framework for parsing what is good and living and beautiful in itself.

A Pattern Language is the second volume of a trilogy of books by Christopher Alexander and his collaborators. In the first volume, The Timeless Way of Building, he explicates his architectural philosophy. In A Pattern Language he proposes a set of explicit instructions for designing and building beautiful spaces: rooms, buildings, streets, neighborhoods, towns and cities. The third volume is about his work designing and building the campus of The University of Oregon.

The Timeless Way of Building makes clear that Alexander’s architectural philosophy is as much about living the good life as about building good buildings. I am not an architect. I do not have any building projects in hand, nor do I wish to. I have no desire to start building a new house and no desire to join a city planning commission. All I want is to live peacefully, creatively, and beautifully in my home, in my city, and in my relationships. Somehow though, the principles of architecture articulated in The Timeless Way of Building have offered me a better way to do the things I wish to do while still ostensibly being “about” the building process.

The Timeless Way of Building is divided into three parts. The first is an eight-chapter description of what Alexander calls “the nameless quality.” The second part is an explication of the tools needed for cultivating this nameless quality. The third is a set of instructions for using these tools to grow buildings and communities that have the nameless quality. These three sections—“The Quality,” “The Gate,” and “The Way”—are also illustrated with photographs that either explicitly demonstrate a feature described in the text or otherwise evoke Alexander’s design philosophy.

It was probably more than two decades ago that I first heard William Morris’ maxim, “Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.” It has hovered on the edge of my awareness ever since. When I am rejecting a food processor (my chef’s knife is just as good) or selecting a new shower curtain (plastic is waterproof but also stiff and ugly) or spending twice as much on a gorgeous, illustrated hardcover rather than buying the paperback sitting next to it, his words float through my mind. The Timeless Way of Building takes this idea and deepens it to reframe every design choice and every behavioral choice. How should we then live? By doing nothing which we do not know to be right and good and beautiful.

Alexander explains that throughout all of human history we have known how to build well. We can see that there is something pleasing, something wonderful, about traditional architecture and old cities and villages. His contention is that this is true of most, if not all, traditional building practices and that it “grows out directly from the inner nature of people.” In fact, our universal impulse is to bring order into the world because every human being “has, somewhere in his heart, the dream to make a living world, a universe.”

Is there a soul that does not resonate to that idea? I cannot imagine being alive and not being moved by his description! Yes, I want to make some living world. Every day, I long for the sense that I have brought something to life, that through my efforts something orderly and harmonious lives. It is this impulse, however imperfectly realized, that drives me to write stories and it is the same impulse that drives me to plan dinner parties. In both cases I dream of bringing disparate elements together into one living whole. Characters and a setting together with narrative structure and judiciously chosen words into a true and beautiful story. Food and wine and the correct lighting and judiciously selected friends into that feast of reason and flow of soul that alone deserves to be called conversation. That Alexander examines this desire in the context of building homes and designing cities is simply illustrative of its universal applicability. Stories and paintings and parties and cozy little living rooms and New Year’s resolutions and bookshops and planned vacations and school curricula and parades and parks and cafes and gardens and journals are all attempts to make a living world, however small it might be.

If we know these things, if Peruvian villages and the city of Florence and English country towns all have some fundamental order in them and please the human soul in something of the same way, even as they are profoundly different from one another, why do most of us live in hideous cities, build houses in barren neighborhoods, worship in sterile gymnasiums, and shop in soul-killingly ugly strip malls? Something about modern culture has changed how we act in the world, how we build, how we inhabit space, and that something has brought forth ugliness in place of beauty.

Alexander argues that our “power has been frozen in us…we are crippled by our fears and crippled by the methods and the images which we use to overcome those fears.” Our fear is that “without images and methods chaos will break loose” and we are “afraid that we will ourselves be chaos, hollow, nothing.” Again, I ask, is there a soul alive that does not resonate to this fear? I look at my life and underneath all kinds of decisions, all kinds of failed plans, all kinds of hard and hopeless and false work, lies this very fear. If I do what I want, if I fulfill my desires, will I be an empty nothing? If I write what I think, will it be chaotic, foolish? If I do what I want will I become a vapid couch potato consuming endless entertainment and never really living? If I write in a journal, will it be stupid, meaningless, shallow, embarrassing? If I design my own clothing or put together my own wardrobe will I look a mess? I read The Timeless Way of Building and realize that instead of falling into the feared error of making chaos, I have instead been “crippled by the methods and images” that I was using to avoid facing these fears.

I tried to be a good girl hoping that my church would want and welcome me. I tried to be hardworking, hoping that my boss would find me acceptable enough to promote. I tried to be a submissive daughter, a supportive wife, hoping to be loved. I tried to be stylish hoping to appeal to others. I tried and tried and tried. And yet, I had to abandon those methods and images in order to survive. They were killing me as I kept trying to fit myself into existing expectations and stereotypes, all the time violating some strong sense of rightness, ignoring some pressing inner need, inadvertently cultivating stress and brokenness.

To survive, I have had to find a new way to live. One that still aims at doing the right thing but does not cripple me. Some way that generates life and beauty and harmony.

What it is that I am in pursuit of is hard to define. Hard to identify. And harder to generate. Alexander calls this the “quality without a name” and spends a rich chapter exploring its reality and corresponding indefinability. What is “the single central quality which makes the difference?” Why is it that we can all say that this building works, that this room is just right, that this town is good and pleasing? Why is it that we can all imagine some beautiful and perfect home, complete with all its habits and accouterments, but we can’t say exactly what it is about that home that is so perfect without describing the whole thing? Because there is a singular quality that is expressed by all these things but it is not static and is made up of the complex web of interactions between structures, the natural world, and the humans that inhabit it. It is not simply a perfectly proportioned room that we love but that room along with its beautiful and comfortable furniture, and the tree outside the window, and the pattern of sunlight on the rug, and the interaction of these with the cat and the child and the visiting grandfather that fully expresses this quality.

Alexander essays a definition of the quality without a name by using seven words and describing them as a series of overlapping ellipses whose center point is the quality without a name: Alive. Whole. Comfortable. Free. Exact. Egoless. Eternal.

The point at which these seven words connect, where they become congruent and where contradiction falls away, is the quality without a name. A building that achieves this quality simply feels right to human beings, and a town or city that achieves this—however partially—is a place we can be at home. Important to this definition is the idea that this quality can be achieved so long as we are faithful to the inner nature of a place, of the materials used, and of ourselves.

And how natural and yet still surprising that this quality that makes for beautiful architecture is also the quality, the selfhood, the congruence that people want and need in their own lives? To be human is to long for a living, comfortable, free, exact, egoless, eternal wholeness. I have spent most of my life trying on various attitudes, opinions, styles, habits, attempting to find myself. So many didn’t fit. They were made for other souls. They were pre-fabricated and cannot be used without distorting the living situation.

Incidentally, Alexander rejects all pre-made and mass-manufactured building materials. Even windows should be glazed on site because every window must resolve within itself the precise needs of the room it will be in and the people who will use it. Likewise you cannot buy a table at a big-box store and expect it to work for your dining nook in the same way as one you measure, design, and make or have it made for you. Leave aside, for a moment, all the practical objections to such a reality and think, if just for a moment, what it might mean to take seriously the need for genuine, thoroughgoing individuality. What would it be like to live in a world where we assumed that every single situation required individual attention? Where every single relationship, between people or between things or between people and things, was considered precisely itself and not some preset, generic, generalized stereotype?

Wholeness, realness, being thoroughly good, thoroughly honest, thoroughly who you are called and created to be is “the central problem of life.” How to become the self—your self—and not some false self, propped up by advertising or consumption, without falsehood, without evil, without exaggeration, without constraint, without failure, without sin? If we are to follow Alexander in building structures and in building the self we have to realize two things: that we must “let go” and that we must work at it. The forces of life must “flow freely” but in construction and in life there is much work for us to do. We must be attentive to the actual situation we are in. We must notice the way the sunlight falls across our particular piece of land. We must consider the way we ourselves use our kitchen table. We must consider our own talents and weaknesses: our actual ones and not the ones we imagine or hope for. We must judge our own energy and our exact relationship to others.

Of course this is overwhelming. Almost comically so. I drive a mass-manufactured vehicle. I wear clothing made in huge factories. I eat food from a supermarket. Algorithms drive the advertising I see on websites. Streaming services govern the available music. The cafe has the same patio chairs I purchased at the department store. My sister’s house was built along with four hundred others the same year by a company who uses only five separate floor plans. On my way to church I drive past more than twenty chain restaurants, some of them duplicates of one another. I live in a culture where it is a disappointment if hundreds of thousands or millions of people don’t want to watch the same movie on the same weekend.

Alexander identifies and develops the concept of the quality without a name and then develops his theory that this quality is embodied in certain patterns. Patterns are the elements of which an environment is made. “The structure of a town or building is…every concrete element [together] with a certain pattern of events.” Thus, we are to understand every element of an architectural project, and perhaps, of a human life as an almost boundlessly complex set of relationships. Relationships between the physical components as well as between each of them and each event that happens near or through them. Thus we can identify an entryway as not only the doorway but also each component of the door—the uprights, the lintel, the width and height of the opening, the door itself and its handle and panels—and the porch or step that precedes it, the space inside with its coat hooks and bench, the changing light of the interior, the mirror—and the acts of entrance and exit repeated over time, the words spoken, the emotion felt as one comes home from a journey, as one carries out the trash or brings in the mail, as friends enter, etc., and ad infinitum.

Good patterns, living patterns, ones which carry the quality without a name, that exist at that intersection of wholeness and exactness, that inspire and fill us with a sense of beauty, are the ones in which every relationship resolves and harmonizes all the forces within it. The living doorway bears the weight physically and visually of the building above it. It creates a sense of transition, shelters people from weather, offers a way to discard outdoor clothing and shoes, protects the interior from the noise outside and from the dirt of the yard, etc. All the forces that come to bear on it, from gravity to a toddler’s desire to escape must be resolved for it to have the quality without a name. Bad patterns, on the other hand, leak forces which then cause other patterns to fail or die. If the doorway cannot bear the physical weight cracks form, which then disintegrate the plaster and distort the frame so that it cannot close. Likewise, if the doorway is poorly lit, or does not offer a step or porch for cleaning off one’s feet, then dirt and disorder will enter the home and make it unwelcoming, stressful for needing extra cleaning, or otherwise unpleasant.

There are two important caveats to this harmony. One: “stress and conflict are a normal and healthy part of human life” and the pursuit of the quality without a name is not a quest to eliminate stress and conflict. If we succeeded in such a goal we would then “atrophy and die.” What we wish to eliminate is unresolvable and destructive stress and conflict that drains us and uses up our ability to function without making or creating anything good. Two: “the life of [a] pattern does not depend on the fact that it does something for ‘us’—but simply on the self-sustaining harmony [of itself].” Because we are not the locus of meaning for all patterns. We develop and build the ones that concern us, the ones that we participate in, but waves on a beach are a living pattern without reference to human observation. In fact, their independence from us and from our control is why we love to watch them. The organic health of a forest floor is a living pattern whether a human obtains food or fuel from it or not.

By now Alexander’s work probably seems like a counsel of perfection: get everything right or nothing works. After all, “each dead pattern is incapable of containing its own forces and keeping them in balance” and “bad or dead patterns leak forces which cause others to fail and die.” But someone as attentive to reality as Alexander could not fail to see and understand that although there are many beautiful places in the world, many beautiful lives, many beautiful objects, there are also no places that contain only good patterns without any flaws or errors. And so toward the end of the book, he offers a corrective to this impression, integrated into his entire philosophy is the idea that every instantiation of a pattern must include “a rule of transformation” because every pattern adapts to its local conditions.

Further, no act of building is ever complete. “The Process of Repair” is an integral and ongoing part of every architectural undertaking. For, inevitably, “we attempt to simulate in advance, the feeling and events which will emerge” but that “prediction is all guesswork” and everything is always “at least slightly different” in reality than even our best guesses can predict. Thus, we are obligated to “keep changing the building” as we encounter reality through its use and we must engage in “thousands [of] self-correcting acts, each one improving and repairing the acts of the others.”

And this is yet another point of recognition. I can see that I have always known this but I did not fully understand it with regard to my inner life because I was not conscious of it in relation to the physical world I inhabit. I have to fix my house bit by bit to make it better, more alive, more whole. It requires constant attention and repair of the most mundane sort: move the knife drawer so that it is more accessible from the butcher block, change the light so that it illuminates the sink better, buy new kitchen towels because these are wearing out. This then extends to the yard whose fence changes as the children grow and whose garden beds need to be moved as certain trees cast too much shade. And then to the house itself as we add a porch and extend the bedroom and replace the tub with a better one. But the whole time I somehow did not see that this was all nothing more than the repentance I was taught in Sunday School. Turn away from the bad, turn toward the good. Apologize. Find a way to do better. Change the physical circumstances if it will help you change the spiritual ones. Build a good habit in place of a bad one.

I said before that The Timeless Way of Building alerted me to my own and the universal human desire to create a living world for ourselves, to live free and happy, to be whole. By attending to the hunger in my soul for beautiful buildings I can also attend to my hunger for a beautiful soul. Alexander points out that a living building is built in the consciousness that it cannot exist forever. The materials that sing to us of the quality without a name are materials which show their age and show it by becoming more lovely. “Soft tile and brick, soft plaster, fading coats of paint, canvas which has been bleached a little.” Likewise, it is only in “the consciousness of death” that the human lives freely, wholly, and without ego.

Death of the person and death of the building are givens of nature. The quality without a name emerges when we “wholeheartedly” accept this reality. If we do not then we “will distort nature, by exaggerating differences, or by exaggerating similarities.” Both exaggerations are failures to resolve the forces present in this situation: the desire to live and create, and the fact that you too will die as all have done and all will do. Unresolved, these forces tear us apart. Resolved, we live alive, whole, comfortable, free, exact, egoless, and eternal.

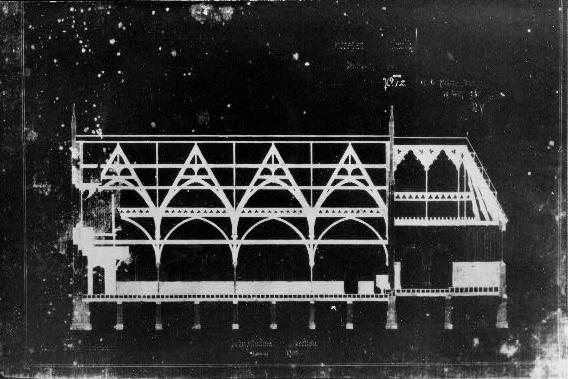

Image credit: Original blueprint for Trinity Episcopal Cathedral in Davenport, Iowa.

“if Peruvian villages and the city of Florence and English country towns all have some fundamental order in them and please the human soul in something of the same way, even as they are profoundly different from one another, why do most of us live in hideous cities, build houses in barren neighborhoods, worship in sterile gymnasiums, and shop in soul-killingly ugly strip malls?”

Villages and cities aren’t designed, at least not ones that last, they’re not like a building, that needs a plan, and since World War II centralization/bureaucratization rules everything, so the organic growth that produces ones that work isn’t even allowed anymore. And so where before communities rose, grew, (sometimes died), changed, reformed, etc., once the central power becomes strong enough we get nothing but strict rules, plans, and abominations like “urban renewal” that only destroy. People like Alexander, Jacobs, etc., aren’t writing from a recent past, they might as well be from another universe for all the chance they have of influencing anyone of any importance.

While I agree that overcentralization is a factor in bad urban design, you’re going too far in conflating the organic city/planned city distinction with the distinction between good design/bad design. It can be the opposite, lots of planned cities work well and lots of organically-created cities ended up bad or no longer exist because they were dysfunctional. It’s all depends on how well they did it, neither organic nor planned cities are a guarantee of success or failure. For example, Spanish colonial cities were all planned and still work today, they draw tourists from all over the world and are much more walkable and beautiful than many planned American cities. Haussmann re-planned large parts of Paris and made it much better. Centralization is an issue, but a small or medium-sized town can be planned well by its own central government if they contract it out to an urban design firm who understands good design. The real issue since WW2 is bad design, largely because engineers assumed the role of designers and designed cities for cars, not for people. See Andres Duany’s books and videos and James Kunstler, the Geography of Nowhere.

Also, the article is correct that it is possible that “Peruvian villages and the city of Florence and English country towns all have some fundamental order in them and please the human soul in something of the same way.” Achieving that fundamental order through a spontaneous organic process, or through planning, are two ways of achieving the same goal.

Yes! And understanding the nature of that order and unity would be the necessary first step in either planning or cultivating it. Alexander would argue that it is not exactly a “spontaneous” process, but the natural outgrowth of broad cultural understanding combined with a steady and persistent process of building and repair.

Comments are closed.