Suzanne Simard’s Finding the Mother Tree and Peter Wohlleben’s The Secret Life of Trees introduced me to the concept of deeply interconnected natural systems in forests. The wood wide web, trees talking to one another, the necessity of nurse logs, the forest mass beneath the soil, the marvelous fungal reality of roto systems. Then Merlin Sheldrake’s Entangled Life deepened my appreciation of fungus and opened my mind to the astonishing way that lifeforms function beyond the crudely visible forms of roots, stems, leaves, and flowers. Robert Macfarlane’s Underland heightened my sense that things were happening deeper than I had known and Tao Orion’s Beyond the War on Invasive Species alerted me to the possibility of a more complex understanding of plants than the good/bad dichotomy.

Of course, Wendell Berry’s essays taught me that tractors are not just about the fossil fuels they burn—they shape the land and the farmer even more than they shape the climate—and that soil health is about much more than what you add to it. And Masanobu Fukuoka taught me that nature requires us to pay attention to learn the effects of what we are doing and the connection between various growth cycles; Robin Wall Kimmerer that the indigenous peoples of the Americas were active managers of their land and that many of the plant species in the “wild” landscapes were actively being cultivated before colonial disruptions. M.R. O’Connor explained the importance of fire and the intense complexity of human use of fire as well as the land’s hunger for it.

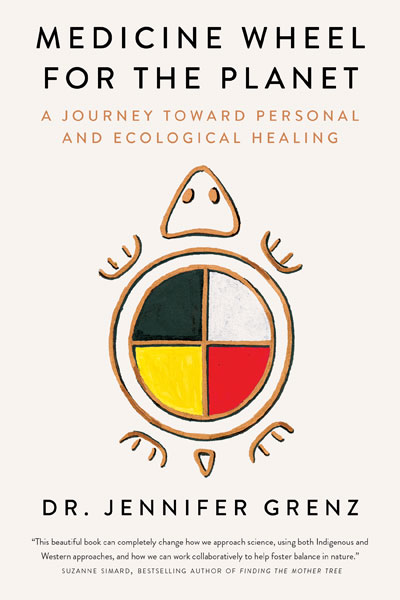

Dr. Jennifer Grenz’s Medicine Wheel for the Planet is an excellent and thought-provoking addition to this conversation. The titular medicine wheel is a ceremonial image that governs the structure of her book, the nature of her work as an ecological healer, and provides a method of orientation as well as a pattern for working through the intellectual, emotional, and relational reality of ecology. Grenz is presenting an argument for a profound shift in our approach to ecological matters. Simply stated, she is merely opening our minds to indigenous wisdom as we attempt to care for the land. However, such simplicity is practically insufficient and philosophically empty. Why ought we to change? How could we make such a change possible? Grenz pursues the transcendental: “The first ceremony for me was to speak truth” (105).

Medicine Wheel is almost as much memoir as it is an argument for changing the modern approach to environmental science. This, of course, is intentional and an embodiment of part of her reasoning. If the indigenous method is relational, reciprocal, and respectful, then telling the story of one’s own journey is necessary and good. In fact, story is a profound way of knowing, one that was once understood in the western world and still is, at least within the Catholic tradition. As Grenz writes, “The notion that empirical evidence is sounder than cultural knowledge permeates Western thought but alienates many Indigenous scholars. Rather than their cultural knowledge being seen as extra intellectual, it is denigrated. It is the notion of the superiority of empirical knowledge that leads to the idea that written text supersedes oral tradition. For Indigenous scholars, empirical knowledge is still crucial, yet it is not their only way of knowing the world around them.” (45-46) Which sounds precisely like the authorities of Scripture (empirical or written knowledge), Tradition (the oral passing down of knowledge), and I might also suggest adding the Magisterium as a parallel to the voice of the Elders in a community.

Grenz argues that the western approach to ecology is ignorant and therefore that it causes damage even as it attempts to repair the environment. The western approach is profoundly crippled because of its limitations. It misunderstands what is good for the land because it imagines some “natural” or “wild” state that hasn’t ever existed. According to one indigenous story, humans were made by Creator to “help keep balance in the animal kingdom” through “their mutual reliance and respect” (150). Because of the trauma and specific history of colonization this understanding was lost, and the continent “Turtle Island” has never been the same. Europeans came to the Americas and did not see that it was a managed landscape; they failed to recognize indigenous agriculture and thus formed the fundamental misunderstanding of wild and natural vs. farmed. This, combined with an exploitative mindset that looked to extract “resources” from forests, plains, lakes, and mines, has led to our ravaged landscape. The “wilderness” is insufficiently managed and the rest of the land is depleted.

Further, attempts at various kinds of repair tend to try to recreate a particular historical moment in a landscape without sufficient attention to how that balance had been achieved (again the “natural” misunderstanding that leaves humans out) and without sufficient openness to possible healthy combinations. “Invasive” species are to be driven out, but without a maintenance relationship no new balance is sustained. Characteristically a kind of “perfectionism” entails “cookie-cutter” restoration attempts that repeatedly and spectacularly fail. And, worse, a kind of risk-aversion in Western scientific methods (funding driven, profit driven, with academics needing publication and therefore needing an answer more than truth) is confined by its “guise of objectivity” which founds its methodology on an intellectual lie (84). It is, of course, rash to avoid one set of risks only to fall into another.

In contrast, an indigenous ecology calls us to attend to the importance of persons in the balance. We are to open ourselves to possibilities. Like children we should be seeking the “beginner’s mind” or “The Time of the Eagle” where we can see and try new things. We are also to change our language in order to change our understanding and behavior, getting away from the tendency toward rigid categorization of species as good or bad, away from language that places persons outside the natural order, and toward language that invokes our responsibility as balancers and leaders. Finally, we are to slow ourselves down, attend to what is before and attend longer than is comfortable, and ground ourselves in gratitude and a ceremonial approach. “Just about every Elder I have spent time with has mentioned how we don’t listen enough these days. We are too busy thinking about what we want to say ourselves, filling the air with our voice” (207).

As C.S. Lewis taught us in The Discarded Image, our model of the universe is of great importance. How we understand ourselves, the relative importance we ascribe to persons, animals, things flows from it. What we consider good and significant is rooted in that model, whether it is an entirely conscious one or not. The popular model of the universe is, as Grenz describes, narrowly focused on profitability and based on a significant misunderstanding of wild vs. tamed and useful (for profit) vs. useful (for entertainment). It is overly simplistic, with each element typically understood in relationship to only one other and that some distorted version of itself. Think of lawns (grass as carpet in front of a private home), or pine trees (to be cut and carried inside for Christmas), or lakes (for going boating on). Even things as complex and significant as forest fires are regarded as bad by my community simply because of the unpleasantness of smoke on an August afternoon in the city. It would be rash not to consider the actual damage of smoke inhalation as well as to disregard the destruction a forest fire can cause, but it is likewise rash to disregard the complex good that fire is: the way it can, if well-deployed, make a forest healthier, preserve meadows, enrich soil, seed new trees, and generally aid balance.

What Grenz is challenging us to do requires us to abandon all such simplification and falsification for a relational model of ecology. The challenge is that this cannot be a simple switch. It is not enough, nor is it even correct, to decide that dandelions are good because bees like them in the spring. That is true enough, but it is only taking one simplistic view (dandelions are weeds and bad) and substituting another (dandelions good as food for bees). As a balancer, you are responsible to consider the dandelion as fully as possible. Observe it. Consider it. Avoid a binary of good versus bad and think of it along the four directions. First, realize that there may be wisdom in some older way of knowing. Second, remain open to any possibility with the “beginner’s mind.” Third, modify language to encompass this new complexity. And, fourth, patiently attend to the full process of balancing mind and heart, old and new knowledges, and the paths that remain open. It is often true that dandelions are the first food for pollinators; it is also true that they sometimes outcompete some other species that may need the bees more. Likewise, it is true that they are edible, leaf, flower and root! But do you eat them and are you grateful, even for their bitterness? “Good work did not lie in a direct answer to a specific question; good work was to pursue a meaningful journey that would provide the community the teachings they sought” (208).

I do have a quibble with Grenz’s framing of the dichotomy between the western scientific approach and indigenous knowledges. Her characterization of modern ecological approaches and of their development in North America is realistic, and so far as I understand it, accurate. Unfortunately, she claims that it is rooted in an “Eden ecology” that comes from a “Judeo-Christian belief that gives people dominion . . . and objectifies . . . the environment as if it is independent from humans” (7). She then frequently describes the problems with the western view as being rooted in some attempt to get the wild “back to Eden” in a way that leaves people out of the picture. While I do not dispute this characterization of the western scientific approach, it does seem to be a misunderstanding of the Christian tradition and a conflation of religious belief and practice with capitalistic and secular exploitations.

In contrast, I believe that it is remarkable how well an orthodox reading of the Eden narrative corresponds to the indigenous understanding of humanity. Adam and Eve were to care for the Garden. Humanity was meant to tend the earth in precisely the way that Grenz describes, as responsible caretakers of the land. It is in the Genesis story that we find the problem, but it is not in the role assigned to humanity but in humanity’s failure to live up to it. The colonizers were not wrong for adhering to an Edenic view; they were terribly wrong for being greedy, exploitative, and ignorant. As Grenz describes, they looked at the abundance of the Americas and saw some “natural” landscape that they then set out to take and exploit.

Christian theology as filtered through selfishness and greed certainly did justify such exploitation for the colonial mind, but the orthodox Christian tradition has demonstrated that shameful cruelty is understood to be an effect of the Fall and not the created purpose of Adam in Eden. It seems to me that this a contrast not between Christian and Indigenous but between a richly and cosmically supernatural perspective and a barrenly exploitative materialist one. The modern materialist view tends to be one that asks only “How?” and never “Why?” This objection is, perhaps, over sensitivity on my part, and yet I think it worth pushing against Grenz’s framing of the Western view as “Eden ecology.” The work of the garden, the creative work of planting and pruning, of caring and stewarding, is part of the goodness of Creation to the Christian. There ought not be unnecessary opposition between Indigenous and Christian perspectives. The creative work of caring for our ecology is hard enough; let us not also misunderstand one another. Believing the goodness of the created world, believing in the sustained though marred Imago Dei in humanity, believing (as most Christians do) in the reality of Common Grace—that glorious gift of God’s goodness to all humanity and to all the Earth—will be the bridge from the Christian to indigenous knowledges. Perhaps it could be a bridge back as well.

Image via Wikimedia Commons