I don’t want to be a hostile reader, nor do I want that for my students. My aim is to be a charitable one, one who acknowledges that reading has the potential to form me and my students not only for the better but for the eternal. I know, however, that it is easier to aspire to this attitude than to consistently embody it.

Deep Reading: Practices To Subvert the Vice of Our Distracted, Hostile, and Consumeristic Age (2024) shares this view by encouraging us as readers, thinkers, and teachers to develop “practices that help us tend to what we read, the way we want to attend to our friends and neighbors.” Rather than viewing reading primarily as a means of getting students to arrive at the right beliefs or worldviews, authors Rachel Griffis, Julie Ooms, and Rachel De Smith Roberts challenge us to view reading as a hospitable activity that might counter the age of distraction.

Where has our ‘sustained, unbroken attention’ gone? In Part I, titled “Practices to Subvert Distraction,” training our attention becomes a way of fostering self-control, of “temper[ing] our desires for what is pleasurable with our need to focus on what is good.” Ideal for new teachers, these first two chapters address attentiveness while reviewing common sense methods for encouraging it in classrooms and other reading communities. They describe the practices of discussion, annotation, and close reading exercises in effective classrooms. While they discuss ideas such as lectio divina, field trips, or reading aloud, the most helpful ideas for my humanities classes come from their reading reflection questions that ask us to consciously think through what our real reading process looks like.

By Part II, the authors see reading as an act against hostility, a conscious act against the culture wars and for the “intellectual and spiritual formation of our students, our book club members, our fellow congregants, and ourselves.” Here we are called to embrace an intention to listen well—charitably, empathically—as we “bypass the ideologies of the western canon.” The subtle hostility toward the “western canon,” as if this were itself some monolith, seems in tension with this section’s stated aim to foster hospitable reading practices, but the book does provide helpful suggestions for prodding ourselves and our students to read less dogmatically and more generously.

To be a charitable reader, Part III argues, we must also push back against consumerism. Books in the classroom are not strictly for consumption. They are not things to ‘get through’ in order to gain something else in the wide world beyond the classroom. No, they are a means of change, not brain stuffing, because a healthy classroom or reading community creates and deepens relationships. Classrooms can and should be spaces of sincere and generous conversation, where ideas are given and received.

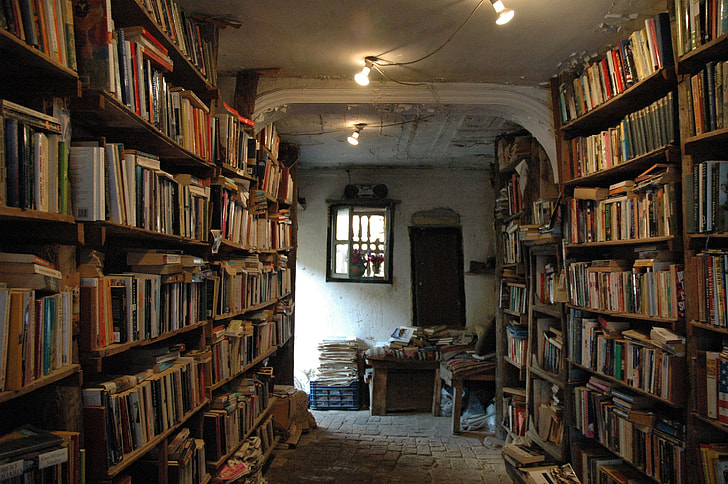

In the final chapter, “Being a Human: Learning to Read for Enjoyment,” Griffis, Ooms, and Roberts speak of the delight, rest, and joy available in reading. They suggest creating environments for classrooms and communities that are ripe for reading, spaces that allow for time to absorb, grow, celebrate, and read in contemplation. Reading is not a binary activity that one either does or fails to do. It is a spiritual practice that requires well-designed habits in order to develop “a faithful intellectual life.” It is a relational act, not a distracted one, a hopeful remedy for a consumerist society.

As a teacher committed to helping my students read well and deeply, I concur with many of the aims articulated by these authors. I found myself, however, troubled by two tendencies in this book. The first is an articulation of hospitality that verges toward pandering, and the second is an inconsistent application of generosity toward some voices but not others.

With regard to the first, when considering how to cultivate attention, the authors argue that reading communities, such as classrooms, should employ a variety of approaches to books. In practice, I agree. I rarely lecture but do read aloud and require the same of my high school students. I add audio excerpts, lessons on dramatic reading, memorization, and the occasional video clip as we study, say, The Crucible or The Aeneid.

But in framing such a variety as a matter of equity, the authors obscure the reality that a teacher’s calling is not simply to meet students where they are, but also to challenge them to deepen their reading practices. While learning accommodations and access for students are necessary, the book praises a multitude of translations, media access, digital sources, and text types in a way that panders to students rather than including them in a rigorous community of learning. A menu of equally ranked choices is not hospitable or inclusive. It’s an overwhelming buffet that appears to be a catering event. Students of any age are capable of more. For instance, requiring the same translation or book edition for a class is not a disservice. It’s a standard. If we follow the claim that reading is a moral practice, high expectations are not wrong.

This leads me to the book’s second troubling tendency: its inconsistent charity toward others. Griffis, Ooms, and Roberts juxtapose this variety of reading methods against some vaguely defined oppression: “Reading aloud and using audiobooks are practices that can dissociate reading from oppressive Western modes of textual encounters.” In a book that calls for charity, the harsh tone and blanket critique were unexpected. Books in the western canon are no more uniformly antagonistic than books in other traditions, and much of the eastern and western canons remain timeless for what we can learn of differing perspectives and mindsets. In my experience, reading is an inclusive act already, one that draws me into the author’s words and world. In itself, how can deep, careful reading of a book be oppressive?

These comments, however, are followed by clear and practical methods to read more hospitably not simply through creating diverse reading lists but through practicing reading as an active conversation. We are part of a long line of readers as we come to a text, and recognizing that company can allow us to avoid elitism or chronological snobbery. It is here that I found hope in the simple view that reading can be a humane practice in which we consider the experiences and questions that unite us to our fellow readers and to authors long dead. Griffis, Ooms, and Roberts cite Alan Jacobs who recommends that we imagine ourselves sitting at the table with the dead, those dead authors as our guests and neighbors. What then would the conversation sound like? Where might we disagree? What can we share?

In advocating for that humane understanding, Jacobs’ vision lends vital common ground. Griffis, Ooms, and Roberts do model that they are willing to engage with “the ideology or worldview of a text[, which is] . . . part of our human response to what we read, a response that can be hostile, charitable, and many gradations in between.” To counter dogmatic worldviews, we should read prudently and widely across time periods and cultures and not avoid difficult content because of fear. Ironically, that may require these authors to set aside their bias against the western canon.

Image via PickPik

Very helpful review! Thank you.

Comments are closed.