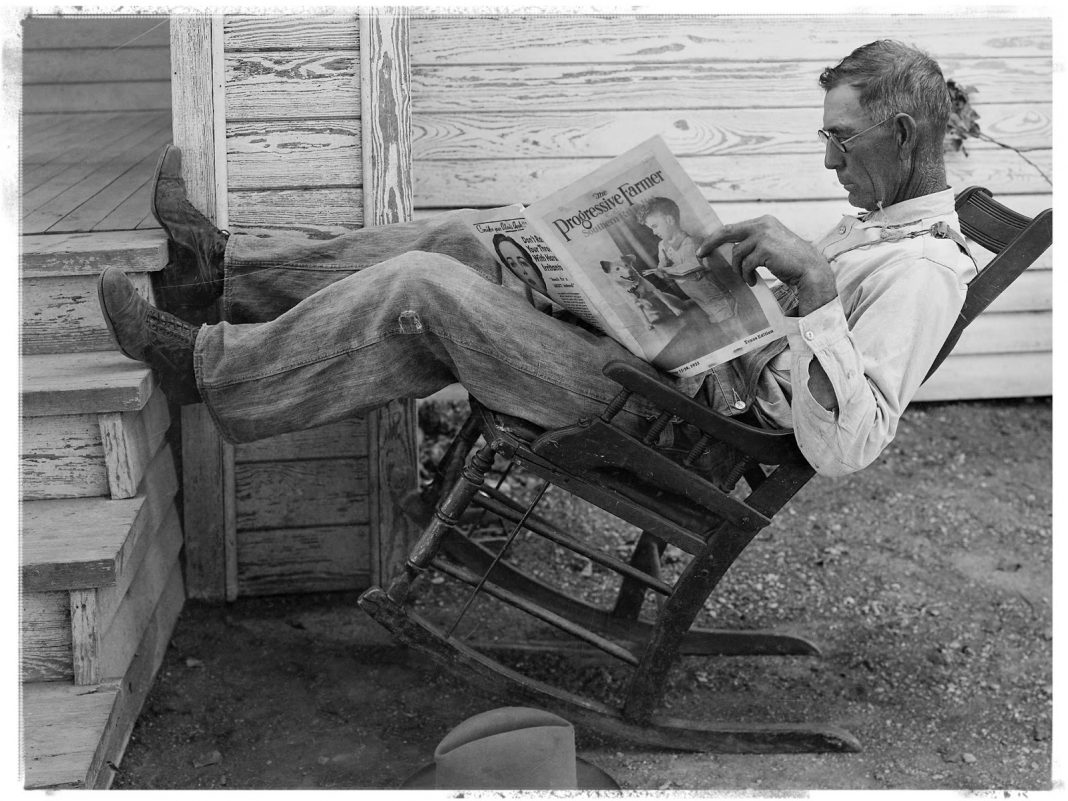

“Love Letter to America.” A.M. Hickman takes a hard look at America’s many dysfunctions: “Then the realization sinks in like news of a dear old friend’s death: There beneath the giant plastic rodent breasts of Betty Beaver’s, you stand not only in the richest country in the world, but in the third-richest state in that country. Looking northward at the placid surface of the old Erie Canal, you also realize you are standing in the bread-basket of that great state. You are standing on the land that made this country as rich and powerful as it now is; the land the opened up the lakes and western rivers, the land that fed New York City for generations — and yet it is languishing in a state of complete and utter decreptitude.” But he still wants to get a party started: “If I have any hopes for the Falling Back in Love With America project, I hope that what I write in the coming months will serve as music for that party — that where perhaps at the outset one walks through the door with some reservations or worries, that in time, they find their heads bobbing to the music and loosening up.”

“The Silver Lining in the Stormy 2024 Presidential Election.” James P. Pinkerton makes a provocative argument that negative polarization and distrust at a national level could open up space for renewed federalism in America: “It’s a simple enough point: Just as splitting the atom releases energy, so does devolving the leviathan.”

“Can the United States Have a Good History?” Daniel J. Fischer commends Jon Lauck’s The Good Country: “by thoroughly making the case that the Midwest deserves more respect, Lauck can credibly consider what his findings mean for the present. He suggests that Midwesterners practice what literary scholar Rita Felski has called ‘stickiness,’ a willingness to commit to particular places even though that limits one’s freedom.”

“You Are Not in Control: The Death of Boethius 1,500 Years On.” Nadya Williams reflects on Boethius’s significance 1,500 years after his death: “what makes Boethius a particularly interesting and relevant figure for this moment, a millennium and a half after his death, is his unwavering commitment to intellectual honesty and to cultivating his own character even when falsely accused of treason—and ultimately executed based on these accusations.”

“‘And You a Catholic!!’” Phil Klay ponders Evelyn Waugh, conversions, and culture wars: “A good quip is a closed form, complete and self-contained, inviting no further inquiry after the delightful shock at the end. It silences not only our pity but also our curiosity. One of the many sins of social media is the way algorithms have convinced writers and pundits that low-grade snark is a substitute for an actual essay responding to work or ideas they don’t like.”

“The False Promise of Device-Based Education.” Amy Tyson eviscerates, but very kindly, EdTech marketing jargon: “many schools have not incorporated a research-based approach to implementing technology in education, nor do they acknowledge the potential costs of displacing traditional methods in favor of screens in schools.”

“The Long Defeat of History.” Jake Meador looks to Tolkien for wisdom about living well in a dark time: “For Tolkien, the demands of honour wed to wisdom and prudence are generally the only demands on us when we consider what we ought to do. History is simply the stage on which we act, playing our part well or poorly. Our feet are set down at some moment in time by forces entirely outside our control, and we must decide how to walk. As the wizard Gandalf counsels elsewhere in Lord of the Rings, “All we have to do is to decide what to do with the time that is given to us.” But this is not how many of us think about the relationship between time and moral choice. Rather than the space in which we make choices, history has come to be one of the central inputs that informs our choices, competing with the claims of honour as defined by the moral law.”

“Life on Earth.” Jude Russo takes stock of a year in the garden and the philosophical and practical benefits of horticulture: “Our peppers were not merely successful, but exuberant. Friends and relatives can look forward to a Christmas of novelty hot sauces with amusing (to me) names: “Creeping Authoritarianism” (Hungarian wax peppers), “The King and I” (Thai prik kee noos), “1893” (Aji pineapple). The processing of peppers yielded many and sometimes painful lessons, foremost of which is the importance of keeping gloves close by.”

“Why Individualism Fails to Create Individuals.” Matthew Crawford draws on Michael Polanyi to develop a key insight: “The paradoxical thesis I wish to consider is this: Real independence of mind can be won only by a sustained process of submission to authority. There is a related paradox: A democratic society, precisely because it requires such independence of thought if it is to be something other than mob rule, requires education conducted with an aristocratic ethos.”

“ChatGPT Doesn’t Have to Ruin College.” Tyler Austin Harper argues, rightly, that the best response to students tempted to cheat with AI tools is to build a culture that celebrates formative, intellectual effort: “The challenge posed by ChatGPT for American colleges and universities is not primarily technological but cultural and economic.”

“My Pleasure: Why Would You Not Want to be Charming All the Time?” Elizabeth Stice commends the virtue of charm: “Far from being servile, being charming can be a sign of confidence. When we are afraid, we act self-interestedly. We withhold—affection, attention, eye contact, courtesies, kindnesses. We get too big or too small. One of the most charming things anyone can do is to be interested in others.”

“‘Democracy’ in New York State.” Bill Kauffman spills the beans on who he’s voting for: “Since democracy is dead in New York, I write in dead persons. This year Buffalo’s Grover Cleveland gets my vote for president. In the US Senate race, I’m going with Dorothy Day, saintly founder of the Catholic Worker movement, and for Congress I will vote happily for my late friend Barber B. Conable Jr., who nobly represented us for ten terms.”

“The Everlasting Man.” Paul Kingsnorth sings the praises of G.K. Chesterton, whom he first read three decades ago, even while articulating some of his frustrations with The Everlasting Man (frustrations I mostly share, as it happens; it is not his best book): “One day, I picked up a copy of Chesterton’s novel The Napoleon of Notting Hill, and was intrigued. On finishing it, I went looking for The Man Who Was Thursday, and then got myself a book of his poems. When I came across The Secret People, his epic, prophetic take on the story of England, I was hooked. Discovering that he had written non-fiction too, I dug into some of that, and soon discovered distributism, the political theory he had developed with his friend Hilaire Belloc, to offer an alternative to both capitalism and socialism. According to Chesterton, this amounted to guaranteeing ‘three acres and a cow’ to everyone who wanted it. This man, it seemed, reflected the paradoxes of my own worldview – only he didn’t think they were paradoxes. Instead, he had a way of writing about them which made them seem the most natural thing in the world.”