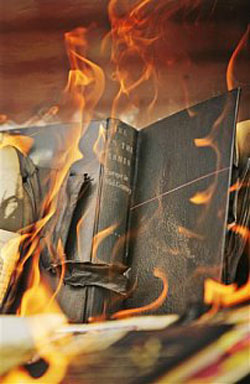

The Rev. Terry Jones has caused quite a stir. For the past week he and his tiny Pentecostal church in Florida have broadcast plans to burn copies of the Qur’an on the ninth anniversary of 9-11. Copies of the Qur’an have been mailed to the church by sympathizers around the country. According to Jones, he and his church are simply doing what God has instructed them to do. A direct message from God is, to be sure, a compelling reason to obey. Yet, Jones is open to God changing His mind, and as matters stand now, the reverend appears willing to call off the bonfire if he can meet with the people pushing for the so-called “Ground-Zero Mosque” in New York City.

The Rev. Terry Jones has caused quite a stir. For the past week he and his tiny Pentecostal church in Florida have broadcast plans to burn copies of the Qur’an on the ninth anniversary of 9-11. Copies of the Qur’an have been mailed to the church by sympathizers around the country. According to Jones, he and his church are simply doing what God has instructed them to do. A direct message from God is, to be sure, a compelling reason to obey. Yet, Jones is open to God changing His mind, and as matters stand now, the reverend appears willing to call off the bonfire if he can meet with the people pushing for the so-called “Ground-Zero Mosque” in New York City.

U.S. leaders including President Obama, Secretary of State Clinton, and Secretary of Defense Gates have all weighed in warning that proceeding with the event could bring grave harm to Americans in Muslim countries. Indeed, while not one Qur’an has been burned there have already been street demonstrations in Afghanistan and dire warnings from Muslims elsewhere. Says one Muslim leader in Indonesia, this act would be a declaration of war. Another remarked that the U.S. government would be culpable if the event was allowed to take place. Clearly he doesn’t appreciate the nuances of the First Amendment.

On one hand, Jones might be construed as a throwback to an earlier time, a sort of Old Testament prophet, moved by the voice of Jehovah, brandishing the sword of righteousness, and destroying idols of Ba’al and any other affront to God. A good number of Muslims should at the very least sympathize with such a figure. After all, the violent protests over the Danish newspaper that published Kurt Westergaard’s cartoons depicting Mohammed were motivated by the same religious zeal. So too, the death threats and murder attempts suffered by Westergaard in the wake of his blasphemy. Fear of violent reprisals prompted Yale University Press to refuse to reproduce Westergaard’s cartoons in a book on the topic (leaving an obvious gap in the story). The Taliban expressed the same impulse when in 2001 they summarily destroyed ancient Buddhist statues ignoring cries of protest from the international community.

So the zealous piety of Jones might be born of the same impulse that motivates Muslims to protest, defend, and revenge desecrations of their holy book and its prophet. There is, of course, one obvious difference, a difference that is too important to ignore: Jones is threatening to burn a book. Those begging him to reconsider are not afraid that angry Muslims will burn a pile of Bibles in retaliation. Rather, they warn (and Muslims themselves validate the warnings) that violence will ensue. That people will be killed.

There is, of course, another possibility. Jones may be attempting to make a point or even seeking his own fifteen minutes of fame. In sponsoring a “Burn a Qur’an Day” he has surely found the latter. It is less clear what point he is trying to make; although, there are important questions raised by his plan and the responses that plan has elicited.

In the wake of the attacks of 9-11, George W. Bush told the country that Islam means peace. He was wrong. Islam means submission. But setting aside that gross bit of misinformation posing as a civics lesson, there is an obvious question: is Islam a peaceful religion? Much turns on the answer to this question. For if Islam is in its essence a religion of peace, we should expect to see Muslims around the world expressing their disdain for violence even as they express reverence for their holy book and the prophet. On the other hand, if the vast majority of Muslims condone the violence or even fail to object to it, we are justified in concluding that Islam is only a religion of peace when it enjoys exclusivity, which is to say, when there are no infidels to terrify or kill.

It might be objected that Christians have, in the name of Christianity, committed their share of atrocities. This cannot be denied. However, the great majority of Christians today would argue that such acts were committed in violation of the commands of Christ and therefore represent a perversion of the teachings of Christianity rather than a logical outgrowth of it. Would a majority of Muslims make the same claim about Muslim-induced violence?

There are, no doubt, Christians who are quietly cheering the actions of Rev. Jones and who hope he follows through with his bonfire. Yet few if any churches are making moves to imitate Jones and his church. Why? We must conclude that either 1) there are Christians who would like to hold their own Qur’an burning event but are afraid, or 2) the vast number of American Christians are apathetic about truth and just want to get along, or 3) that the vast number of Christians embrace principles that forbid them from imitating Rev. Jones even though they agree that Islam is not the true religion. The first is the product of cowardice and the second of unseriousness. The third option, however, suggests that strong religious disagreement is possible without aggressively seeking to offend or insult those with whom one disagrees. It suggests that loving one’s neighbor includes treating him with respect and seeking to persuade rather than humiliate or enrage.

Let’s reverse the situation for a minute. Imagine that an obscure Imam in Kuwait decided to burn a pile of Bibles to commemorate the end of Ramadan. What would happen? If—and this is a big if—the story was even considered newsworthy by the western press, a couple of religious leaders might be interviewed. They would express their disagreement with the Imam and shake their heads sadly. Some commentor might remark on the freedom of all people to express their beliefs even if they are unpopular. Nothing more would be done. No protests. No rioting. No death or even the threat thereof.

It’s not difficult to imagine how this tepid, even pathetic, response might be construed as weakness by those who were not raised to believe that the freedom of expression is somehow a right enjoyed by all human beings by simple virtue of their humanity. It’s not difficult to imagine observers who conclude that what appears to be apathy indicates a vacuum at the core of western religious belief.

It may be true that much of the west is currently mired in a slough of religious indifference that manifests itself in frenzied consumerism, hedonism, and patent irreverence. To the extent this is true, the zealous Muslim observer scores a valid point against the west. I recall walking down Bourbon Street in New Orleans two weeks after September 11, 2001. It was nearing midnight on a Saturday evening. Despite the recent national trauma, things were cooking in the French Quarter. An atmosphere of unrestrained hedonism permeated the crowd, loud jazz music provided the ubiquitous score, and neon signs advertising live sex acts flashed above dim entryways standing like portals to another world. As I walked down the street it occurred to me that if Muslims in the Middle East think this is an accurate depiction of America, well, no wonder they want to bring us down.

On the other hand, the American response to a Muslim cleric burning Bibles might indicate an important fact about Christianity and about the American Constitutional order. Christ taught his disciples to turn the other cheek. To love their enemies. To pray for those who persecute them. Christianity at its best is a religion dedicated to loving God and loving one’s neighbor. Thus, the proper Christian response to the Bible burning Imam is to pray for him. To pray as Christ did while on the cross: “Father forgive them.” Peaceful persuasion rooted in prayer and characterized by love is the Christian ideal. Protests and violence (or the threat thereof) is not in keeping with the Christian faith; although, plenty of Christians have veered down that road to the detriment of the very faith they claim.

The American Constitutional order is one historically rooted in the Christian faith but separated from any established national church. In that sense, the American Constitutional order is secular in form but an outgrowth of a culture permeated by assumptions about human nature and moral truths born of Christianity. As a result, we enjoy a political sphere that can be influenced by the religious sphere while at the same time citizens are free to worship as they please and the state has no say over the content of religious beliefs. This distinction helps to foster the possibility of religious pluralism whereby individuals of differing faiths learn to co-exist while remaining steadfast in their religious commitments.

There are no Muslim states that effect the separation of the state and the church save Turkey, an experiment imposed in the early twentieth-century by a strong ruler who was attempting to help Turkey become a modern nation. While Turkey certainly provides some evidence in support of the hope that Muslim nations can establish political institutions that are formally separated from the dominant religious institutions, the jury is still out and recent trends suggest a resurgence of Islamicist control. So the question remains: can Islam exist as a majority religion in a nation committed to religious pluralism and freedom of expression? This is one of the great questions of our time.

On this anniversary of the 9-11 attacks—attacks that killed not only Christians but Jews and Muslims as well—men and women of good will and of every faith can recommit themselves to peace. To prayer. To good works born of love. And to using the gift of language to champion truth. For the ability to communicate with language, to reason, to reflect, and debate (and the freedom to change one’s mind) is part of what binds us together as human beings and reflects what is best about us. Attempting to persuade by force or fear is not persuasion at all and merely highlights the worst part of our natures.

Thanks Mark,

I wrote an open letter–that I posted on a less popular site, mine–a few days ago.

There are sound Biblical reasons to not burn the Quran as a public statement.

An Open Letter to the Pastor and congregation of Dove World Outreach Church in Gainesville, Florida: Pastor Jones, you and I have not met, and I’m not familiar with your church. I was glad to read a statement attributed to you, that your ministry stands for the “truth of the Bible.” That is a passion that I share. It is on that basis, and that we both lead flocks entrusted to us by the Chief-Shepherd, that I ask you not to burn a copy of the Quran.Several of the news articles I have seen and heard ask you to reconsider Saturday’s ceremony, because it is offensive to Muslims, or because it endangers people–in particular members of our armed forces. I agree in part with your reply to these critics. While these ought to be, and I am sure are, matters of grave concern to you, they are not sufficient reasons to compromise the truth. However, I would ask you to consider the following: Islam is a religion that knows no separation from the state. In the mind of the Muslim there is no secular and sacred. A “good” Muslim government provides an environment in which its citizens can–in a sense must–be good Muslims. Of course the Mosque is in total support of such civil rule.The church, on the other hand, always has been, and very much needs to continue to be, counter-cultural. While Christians are instructed to be good citizens, we do so in full awareness that we are citizens of another, a greater, an eternal realm. The civil authority put our Lord to death, and sentenced millions of our sisters and brothers to the same fate. The Bible does not encourage us to expect much more from the goverment. We are to be the conscience to our nation, not the Bureau of Publicity-stunts.Yes, we are at war–ideological as well as military–but it is not the task of the church to wage that war. Let us not repeat the mistakes of the Crusades.

While we disagree with the truth claims contained in the Quran (and other purportedly holy books that contradict the Bible) we ought to treat these books with respect–at least in the presence of those who honor them.When the Apostle Paul was building his case that all the world stands guilty before God, one group of people he addressed was his own nation, the Jewish people. Of course Paul’s countrymen were adamant about avoiding any hint of idolatry (Romans 2:22). The apostle challenged them, however, with the possibility of having desecrated temples through robbery. Apparently this was a practice that was not unknown. When Paul and his companions were brought before the judgment seat in Ephesus it was said in their defense that they were “neither robbers of temples nor blasphemers of our goddess [Artemis].” (Acts 19:37)Acts of desecrating the objects of worship of others–even false objects of worship–are not in keeping with the pattern we find in the New Testament. (The fact that we do find such actions in the OT I can’t consider at this point, beyond saying that we know things this side of the cross that were unknown in that era.)

When Paul found himself in one of the most pagan places in the world, Athens, he did not go about knocking down or defacing the idols and altars to false gods that were there in abundance. Rather he used the presence of these objects of worship, and the hunger in the hearts of the Athenians that these objects brought to light, to engage in one of the most brilliant pieces of evangelistic discourse ever recorded (Acts 17).

We are told, “Bless those who persecute you; bless and do not curse.” (Romans 12:14, NASB95) And to not “pay back evil for evil to anyone. . . . If possible, so far as it depends on you, be at peace with all men.” While burning a copy of the Quran might make some of us feel courageous and righteous, I would recommend that which takes far more courage, and not only feels righteous, but is righteous and spreads righteousness.

Some folk I know have offered to study the Quran with nominal Muslims. As the emptiness of the book–and even more so, the emptiness it leaves in the heart–is made clear, my friends have been able to share the truth of Jesus Christ with these folk.

Another friend of mine–a tall red-head (well, it is mostly gray now)–pastors a church and leads a school in a Muslim land. He has not led followers of Mohammed to to become followers of Christ by burning copies of the Quran. He has done it by loving those whom others–even their own Muslim neighbors–have rejected. That kind of love will shine brighter and farther than any fire you will start this Saturday. Pastor Jones, I urge you not to burn the Quran, not because it is risky, but because it is wrong. Sincerely in Christ, Howard Merrell

While Turkey certainly provides some evidence in support of the hope that Muslim nations can establish political institutions that are formally separated from the dominant religious institutions

I think the Orthodox remain skeptical.

Mark,

Your essay is excellent. I had similar, not exact, thoughts:

The pastor in FL intends to make a symbolic gesture on the anniversary of 9/11. He intends to exercise his right of free speech by SETTING FIRE to the so-called “holy” book of the people who SET FIRE to the bodies of almost 3000 of our fellow citizens.

Regardless of whether this pastor’s symbolism makes any sense or has any valid meaning (which I would contend it does), he is NOT proposing to burn every Koran in the country or to ban it from libraries or bookshelves, to kill Muslims, or to commit arson against Mosques. He intends to make a statement by means of a speech-act by burning one book.

ON THE OTHER HAND, the most obvious and visible and widespread response of those who practice the so-called “peaceful” religion of Islam, is to threaten–with actual intent–to BURN BUILDINGS AND KILL PEOPLE (AGAIN!!!) because of a speech-act by this li’l ol’ pastor in Florida.

Why do some people want to deny the pastor his liberty?

Why do some people suggest that this pastor’s speech-act is so extremely insensitive and offensive as to be lunatic or criminal, while Christians are expected to abide millions of infanticides as inviolable “private” and protected acts, or abide cow-dung on images of Mother Mary and a Crucifix submerged in urine as inviolable protected acts of artistic expression?

Why are the sensitivities and beliefs of Christians deemed to be vestiges of an archaic, provincial superstition that need to gotten-over, but the sensitivities and beliefs of Muslims deserve to be understood, appreciated, accepted, protected, and conserved.

Why are modern-day Christians–who in numerous and unheralded ways dedicate their lives to selfless charity, generosity and love every day–viewed and treated in this country as if our religion were the primary source of intolerance, hate and war in the world, but modern-day Muslims–who in numerous Islamic societies around the world continue to live as barbarians, practicing suicide bombings, beheadings, stonings, genital mutilations, etc.–are viewed as peaceful, holy, tolerant victims of the Western world’s oppression?

And why–for the life of me I can’t figure this out–why has the modern-American liberal fought ceaselessly for decades against Christian religion and acts of Christian worship, but fights in every instance in defense of the practice and promulgation of the UNDENIABLY TOTALITARIAN/FASCIST/OPPRESSIVE/SEXIST/HOMOPHOBIC/VIOLENT motivating forces of Islam?

Although I doubt that the FL pastor and I view the Creation and a Christian’s imperatives within the Creation in the same way, I say WITHOUT QUALIFICATION that I am certain I would rather live in a world governed by this pastor than by the barbaric ideology and legal/political constructs of the overwhelming majority of Islamic ruled countries and societies.

Unfortunately, it is very easy to test the theory that there would be a lack of outrage is the situation was reversed. One reason that the Imams do not burn bibles is that it is very hard to find one in the most Muslim parts of the world. So instead, they burn Christians, or at least their homes and churches. For example, whatever one thinks of the Iraq war, it has been a disaster for Iraq’s Christians, and the same is true whenever Muslim parties gain power.

“…the great majority of Christians today would argue that such acts were committed in violation of the commands of Christ and therefore represent a perversion of the teachings of Christianity rather than a logical outgrowth of it.”

Mark, like you, I would find it comforting to think that a majority of Christians would argue that the atrocities you alluded to represented a perversion of Christianity, but I see no evidence whatsoever that this Christian majority is deliberately making any such argument. My discussions with Christians since 9-11 (and the attacks on Afghanistan and Iraq) have been peppered with justifications for pre-emptive war, torture, rendition and other atrocities, often justified by Jesus’ claim that “I come not to bring peace, but to bring a sword.”

Which is worse, or more virtuous if you prefer – to belong to a religion that is really violent but masquerading as a religion of peace (as Islam is described by the Terry Joneses of the world,) or to belong to a religion that proclaims peace, justice and the sermon on the mount but yet is so easily perverted into a religion of revenge and violence?

I really don’t see any practical use to comparing Islam to Christianity if the ultimate goal is to tally up all the pros and cons, assign a value and declare one the winner by virtue of beating the other by a few percentage points.

Artie,

I agree that tallying points is not the issue. I believe it was Gandhi who said the thing that kept him from being a Christian was Christians. There are plenty of atrocities committed by Christians that are an embarrassment, vile, and harmful to the faith. Ultimately, what I’m trying to ask is this: is there a peaceful core to Islam that allows it to co-exist in a pluralistic society? Of course, there are plenty of Muslims in the West who are fine citizens and peaceful neighbors. This is cause for hope. The question, it seems to me, is whether or not this is possible when Islam is the majority religion and when Muslims are in charge politically. Despite other problems, Christianity has shown itself capable of doing this. So on one level, I am not even making a claim about the truth or falsity of either religion but merely about the possibilities of each to thrive in a pluralistic society where basic freedoms of expression and religious belief are respected.

Dr. Mitchell,

I miss studying under you and benefiting from your wisdom. This article was an absolute breathe of fresh air. You’ve just said everything I’ve felt but haven’t known how to say.

The response of Christians to this whole fiasco has often fallen to two extremes: lack of love, or false love. In the first, people speak out the truth about Islam, but yet encourage these burnings in a hateful “those Muslim terrorists deserve this” manner. More commonly, many Christians fall into the second category, spouting off politically correct sound-bites about Islam being a peaceful religion. Like you point out, the response to this situation has proven contrary. Some churches, I read today in the news, have gone so far as to have Koran readings in response! Love that exalts lies is no love at all.

Your article, on the other hand, expresses both love and truth in an overwhelmingly eloquent manner.

Thanks.

Kenny Ly (PHC class of ’09)

“…is there a peaceful core to Islam that allows it to co-exist in a pluralistic society?”

For me, there’s not a simple yes or no answer to that question, and I would argue that the question could be asked of Christianity as well. But for the sake of discussion, let’s go with Terry Jones and the 20% of America who believe that Obama is Muslim and just posit that the answer is no, there is not a peaceful core to Islam that allows it to co-exist peacefully. If Islam is the violent, evil religion, are American Christians justified in making a mockery of their own religion?

I remember Billy Graham’s son Franklin Graham calling for Holy War after 9-11, and despite the pleading of the Pope and the Methodist Bishops, Bush ignored his own Christian faith and attacked both Afghanistan and Iraq based on lies created by his second in command.

Good ol’ Christian America spends more on its military power than the rest of the world of combined. Is this what Jesus meant when he said he came not to bring peace, but bring a sword? Would Jesus have sanctioned the over throw of Mossadegh to make Iran’s oil more readily available to Americans? Would Jesus have sanctioned the installation of US military bases in Saudi Arabia, home of Islam’s holiest sites? Would Jesus have sanctioned funding both sides of the Iran-Iraq war? Would Jesus have funded the Mujahideen?

Some Wendell Berry, from Thoughts in the Presence of Fear:

XVIII. In a time such as this, when we have been seriously and most cruelly hurt by those who hate us, and when we must consider ourselves to be gravely threatened by those same people, it is hard to speak of the ways of peace and to remember that Christ enjoined us to love our enemies, but this is no less necessary for being difficult.

Ultimately, what I’m trying to ask is this: is there a peaceful core to Islam that allows it to co-exist in a pluralistic society?

This is a question that has been asked ad nauseum and its frankly, not worth responding too. Why don’t you guys read Cavanaugh’s book “The Myth of Religious Violence.” Cavanaugh has an eminently reasonable analysis of what is usually termed religious violence.

Let’s face it guys, our American government is culpable for a huge amount of violence that being overlooked here. It certainly outweighs the sporadic terrorist attack that happen in Muslim countries and abroad. There is no question about it. Tally the numbers for yourself. The difference is that the media focuses in on one and not the other. It makes connections between one sort of violence and religion and not another.

If we Americans had a media that covered the sort of wanton destruction that carried out by our government abroad we’d have a far different position on this whole discussion. Without seeing that one can’t make sense of why there is so much violence abroad accept by appeals to barbarism and religious irrationality, which are hardly explanations for such widespread phenomenon.

In the name of localism, lets not fall into parochialism.

Ed,

I am perfectly willing to acknowledge the injustices perpetrated by western nations. Cavanaugh’s argument about the complicity of the nation state, itself, may be correct. However, I’m asking a simpler question. In the U.S. a Christian can freely convert to Islam. He might suffer some kind of ostracism from family and friends. People might think him odd. In Saudi Arabia a Muslim who converts to Christianity is killed. To what do we attribute the difference? Do you agree that the difference is significant? If so, then my point is not parochialism masquerading as localism but a serious question in need of a serious answer.

In the name of localism, lets not fall into parochialism.

Great line. I’m sure to “borrow” it at some point in the future.

As for Cavanaugh’s book, we have indeed reviewed it in these pages:

https://www.frontporchrepublic.com/2010/06/lethal-loyalties-dulce-et-decorum-est/

Dr. Mitchell,

I want to recommend a paper written on Islam from an analysis of islamic jurisprudence. A friend of mine wrote this thesis and spends his time traveling in hopes of debunking the myths Edward Said spread about the West through Orientalism. I would really appreciate your thoughts in light of current events.

http://www.carlisle.army.mil/DIME/documents/20080107_Coughlin_ExtremistJihad.pdf

Ultimately it will boil down to the question of “Which tradition, whose authority?” By what authority can x claim that his interpretation of the tradition is the correct one?

I want to preface my comments by saying that what Mr. Jones is doing is perhaps vain, but more importantly profoundly unchristian. What I really wanted to address however is the discussion on Islam and the fundamental error that is made making this discussion almost completely unenlightening. That error is to view Islam as some sort of great uniform monolith that can have grand generalizations made about it. Islam is incredibly diverse with different groups differing on just about everything. Are there angry, violent, murderous Muslims? Of course, we see it all to often, but that is nowhere near the whole story. I have spent a lot of time in Iran and in that country there is a loose group known as the religious intellectual movement who has for a long time been pushing for things like more freedom, more human rights and a governance model closer to secularity while arguing strictly from the religious perspective of Islam. Many of it’s leaders have been jailed or exiled (eg. Dr. Soroush), but it has significant support and is still very active in Iran, particularly in association with the green movement. Unfortunately when ideas collide with force the result is not always positive. Although probably most advanced in Iran, this type of thinking is not minor or limited but has been continuously growing wherever Muslims live. This is just one example of which there could be hundreds, but the point is that to speak simply of Islam is to descend into meaninglessness. I think that the West has been familiar with Islam for long enough, and there is certainly enough western scholarship on Islam for us to be having more nuanced, and accurate, discussions.

For those who are interested there is an interesting open letter Dr. soroush wrote, that while perhaps filled with a little hubris, may be of note. It’s called, “Religious Tyranny is Crumbling”:

http://www.drsoroush.com/English/By_DrSoroush/E-CMB-20090913-ReligiousTyrannyisCrumblingRejoice.html

To summarize my earlier comment, the question is not, is Islam a peaceful religion? The question is, what forms of Islam are peaceful and positive forces in the world and which are violent and destructive? And what should be our relations with these two groups and the varying shades of grey in between?

Mark,

There are plenty of laws in Saudia Arabia that make no sense, even to Muslims. But why use Saudi Arabia as the prototype? Such laws are in need of reformation and there are many Muslims who are making that demand.

For all those wondering about how Islam can deal with pluralism, maybe a more instructive example is malaysia. A country predominantly Muslim, and with a high level or religious observance but with large Hindu and Chinese minorities. It’s a much more useful example.

Two more things should be kept in mind here. 1) The expectation that religions should be indifferent to conversions out of their fold is really a liberal demand, because it assumes a sort of consumer attitude towards religions. 2) However, religions must recognize limits to the sort of discouragement against converting out, and accept the outcome of a sincere conscience and clearly the law in saudi does not recognize this with its death penalty and should be opposed. 3) When dealing with these issues in the context of the Muslim world one can’t ignore the colonial legacy in which there was a coercive imposition of Western culture, opposition to Islam and the local culture by the colonizing country and often an attempt at missionary activity and conversion. These often went hand in hand. Missionaries became adjuncts to the colonial enterprise. This politicizes religion and when that happens it hardly becomes an issue merely of personal conscience but also of political allegiance.

All these nuances need to be added to whatever discussion takes place on this issue.

It seems that there is ignorance on both sides of this debate.

Ignorance in the Islamic world equates the acts of a hateful, so-called Christian pastor with the views of all Christians and the U.S. as a whole. The result is the threat of violence against American troops and Americans abroad.

In the U.S., equating the acts of 9/11 terrorists with the views of Islam is a sign of ignorance of the central teachings of one of the world’s great religions. A central question of this essay — “Is Islam a peaceful religion?” is an example of this ignorance. The counterpoint to passionate Muslim reaction to Pastor Jones is not the reaction to hypothetical Bible burning in Saudi Arabia but the very real and passionate opposition by many Americans to the opening of an Islamic community center in Manhattan.

How do we respond to ignorance? It would be easy to say that the issue is black and white — that Pastor Jones should be able to burn his books and that an Islamic church should be able to build a community center two blocks away from the former site of the World Trade Center, essentially that the views of the ignorant should be ignored.

The better, if less satisfying, approach is to engage in discussion with others of opposing (possibly ignorant) views and seek both to teach and to understand.

The articulate views expressed in the essay on the application of the First Amendment are not inconsistent with this second approach. The First Amendment is a very narrow set of protections preventing state interference in expression and worship. Nothing in the First Amendment requires that private citizens accord all views equal weight or even tolerate opposing views.

I am encouraged by the debate that has resulted in a change, however tentative, of Pastor Jones’ views just as I am encouraged by the debates that take place in response to this essay and other essays on this site.

Mark, I did find your article to be of great interest, and enlightening on a certain level — especially in its sincere, internal Christian character. In the broader scope, where it attempts to raise questions about the natures of Islam and Christianity, I also feel that it did so honestly and indeed managed to raise some interesting questions out of some significantly more interesting thoughts about the relationships between these religions and pluralistic societies.

However, some of the objections that have been levied here are significant. When we advance to hypothetically reverse the Quran-burning scenario and analyse the probable results, we have to keep something in mind: Islam is an embattled demographic, historically and contemporarily (and perhaps this fact is in itself telling upon the face of certain questions of grand validity, but this is for a different discussion), and more than that, predominantly Muslim nations have been physically on the receiving end of predominantly Christian military campaigns for a very long time. Many of the countries that would predictably react with violence to Quran burnings are militarily occupied to some degree by armies that must undeniably be recognized as ‘Christian’ in character and allegiance. In certain unsurprising cases, this means they are literally under military occupation. In others, it means there are bases upon their soil, sending a very specific message in terms of relational control.

The same cannot be said in the reverse. A bible burning in Turkey, Iran or Saudi Arabia means absolutely nothing to us. We have, in some very unique sense, no real reason to view this as symbolic of our situation. Muslims in Muslim nations do. Of course, I don’t say this to condone such violent response. I agree with your extrapolation of this wholeheartedly. But, I am not so certain that if we were to truly and justly portray a reversal of roles we as Christians would, and I suppose this with deep regret, handle ourselves en-masse much differently. A small minority of honest Christians would bear the torch of Truth, but the body, I confidently venture, would don the role of desperation. Desperation is violent, and when the Christian West has borne its role, we have, under the decree of popes and kings alike, exhibited the worst, most violent attributes of man with hubristic certainty.

Jim and Joshua,

I appreciate your very insightful comments. It’s mature analysis like both of your own that makes me hopeful for honest, open and sincere dialogue, and also make me very proud to be an American.

Cheers.

Ed

Mark raised the question: “can Islam exist as a majority religion in a nation committed to religious pluralism and freedom of expression?”

In a follow-up post he asks, ” In the U.S. a Christian can freely convert to Islam. He might suffer some kind of ostracism from family and friends. People might think him odd. In Saudi Arabia a Muslim who converts to Christianity is killed. To what do we attribute the difference?”

Ed objects that Malaysia would be a better point of discussion. I have no idea if the following article is accurate, or what follow-up has taken place in the last three years. Perhaps Ed, or someone knowledgeable could help.

http://www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1626300,00.html

It seems that one of the points of ignorance that has been raised in this discussion, and the broader discussion about Islam and Christianity–indeed about a great many issues in today’s world–is the relationship of church (or faith) and state.

As I understand it–correct me if I am wrong–Islam looks to the state to support, even enforce, religion–Sharia law. There is a significant portion of Christianity that holds its version of this view. I come from a Fundamenalist background. The Moral Majority was (is) one expression of this melding of state and faith.

Christianity, however, was born under a governmental system that was hostile to it. In many places (including some Muslim lands where Christians are persecuted) it continues to thrive today under such hostility. Many of us regard the idea that government should in any way support us in our faith as something that we have no right to expect.

I am glad that Jones did not have his Qur’an burning ceremony. Had he brurned Islam’s Holy book, though, I would have no problem saying that what he did had nothing to do with America per-se. Our’s is a nation that gives idiots who claim to have heard from God, but didn’t, the right to do offensive things as long as they do not violate the law. In the same way America gives an Imam, who is inconsiderate of the grief of thousands, the opportunity–if he can raise the money and jump through the bureaucratic hoops–to build an Islamic Center where no one who desired to be a good neighbor would. In other words, unlike a majority of Islamic nations, ours is a nation where our citizens and even our guests are so religiously free that they are free to offend. (As I understand Biblical Christianity, as a follower of Christ I need to extend that right to others. but likewise as a follower of Christ I need to refrain from needlessly offending others, even, perhaps especially, those I regard as wrong.

Many Christians, and even fewer Muslims are unable or unwilling to make these distinctions.

Thanks everyone for a stimulating and civil discussion. I have a couple questions to address to various individuals in the hope of better understanding our differences and perhaps dissolving some of them.

Devon,

Granted that Islam is not a single monolithic entity. I take it you are suggesting that there are various traditions within Islam and some are more inclined to peace while others are not. You give an example of a group in Iran. Is there a particular tradition that is more inclined to peace or merely individuals and individual groups so inclined? If the former, what is it about the tradition that inclines it to peace? If we are simply talking of individuals and groups, what makes them different (in terms of their understanding of Islam). Do they have a theology of peace, something akin to the Quakers? Forgive my obvious ignorance on this point.

Ed,

I used Saudi Arabia simply as an obvious example. Would my argument have been any weaker if I used Kuwait, Turkey, Morocco, or Pakistan?

I never suggested religions should be indifferent to conversions. Any religion that emphasizes conversion cannot be indifferent about that. But, of course, there are plenty of responses to conversion that don’t include killing or lesser forms of persecution.

Your point about colonialism is a good one. Yes, history matters and these issues are complex.

Jim,

That there is plenty of ignorance to go around is no doubt true. I suppose if we all admit we have plenty to learn, that would be a goo place to start.

However, I have a couple of questions.

You argue that it is wrong to equate the attacks of 9-11 with the views of Islam. Well, is it really that simple? The attackers were all Muslim and they apparently were motivated by their understanding of Islam. It may have been a wrong understanding but they were surely not a handful of oddballs. Plenty cheered them on.

You suggest that a better analog to the Qur’an burning pastor would be the opposition to the Muslim center in Manhattan. That strikes me as incorrect. In fact, would there be this opposition if the proposed site was not in the same vicinity as the 9-11 attacks? That there are Islamic centers and mosques in other parts of Manhattan as well as in every major city in the US (and plenty of minor cities) indicates that this issue is not simply hatred of Islam. If the Imam in charge agreed today to move the site a mile north, most of the protesting Americans would say “great, build it.”

Joshua,

That part of the resentment is caused by American foreign policy that includes the occupation (or at least a military presence in) Muslim countries must be part of the discussion. And I quite agree that if the situation was reversed, there might be some Christians waging some sort of holy war. As I said above, I’m not trying to claim that historically Christians have been without blame or that so-called Christian nations have not committed atrocities with the worst of them. However, I can point to various aspects native to Christian theology that provide a robust context for peace, military restraint, love of neighbor, etc. Is there, for instance, an Islamic pacifist tradition? Or a just war tradition? Or a theology of human nature analogous to the view that each person is made in the image of God and thus is inherently valuable? I’m not asking for exact parallels, but resources in Islam that would facilitate outcomes that include respect for the integrity of human lives that includes freedom of conscience.

Again, thanks for the civil and intelligent discussion.

Is there, for instance, an Islamic pacifist tradition?

If I could recommend a paper by a dear friend of mine, Prof. Muhammad Legenhausen entitled an “Islamic Just War Pacifism.” He is an American, studied at Rice University, and teaches Western philosophy and religion in Qom, Iran. He’s also written a review of MacIntyre’s “Whose Justice? Which Rationality?” thats also online.

http://www.aimislam.com/resources/14-philosophy/762-islamic-just-war-pacifism.html

The problem with Mark’s article is it is pretty accommodating to the general modernist, liberal mindset. That is fine but it is not necessarily very “traditionalist” but then again we traditionalists need to decide exactly where we stand on some of these issues.

Take separation of church and state, what are viable traditionalist positions? I certainly think that the liberal complete prohibition on any official or public support for a traditional belief and values system, now including even prayer in state schools or statues of biblical scenes in courthouses, is not a traditionalist position and if that what Mark means by separation of church and state then most traditionalist Christians would not support it.

These are hard questions but the attacks on Muslim culture are so bound up in them that they need to be at least approximately answered, as does the general traditionalist view on religion, the state and society. Let’s not forget that, at least from my own British standpoint, we should be more worried about the secularists and liberals more than Muslims. That is the secularists and irreligious that threaten us, by which I mean at least us Brits, most. I’d hate to score points against traditionalist or even fundamentalism Islam only to help path the way for further victories for godless liberalism.

Obviously non-modernist Muslims cannot have it both ways. They cannot expect us to give up the liberal critiques of them on the one hand and then stand by secularism, multiculturalism and other modernist, liberal tolerant nonsense when it comes to our own nations, societies and cultures.

It is worth pointing out that both Saudi Arabia and Iran, being fundamentalist, are very much influenced by the modernist West. Fundamentalism is about turning religion into an ideology and quite distinct from traditionalism.

Wessexman,

As long as the political reality is the modern, pluralist nation state, I’m not sure how we can avoid incorporating some modern liberal notions into the discussion. Can you see a way beyond that? I’m perfectly happy debating the relative merits of the modern nation state, but in terms of our current situation, that’s what we are dealing with.

By a separation of church and state I mean no state religion. Not, as some would have it today, the complete privatization of religion.

Your point about the nature of fundamentalism is a good one. How is the debate changed when the categories of fundamentalism and ideology are introduced?

Mark: I think the comparison to mosque construction is sound. You seem unaware extent of opposition to new mosque building projects. There have been protests in Tennessee, Michigan, Texas and California. Occasionally they have been opposed with violence: the FBI is currently investigating arson at the site of the proposed new Murfreesboro mosque in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. Those protesting most vigorously are at the very least, nominally Christian. They seem either unacquainted with or uninterested in the secularism you commend.

You claim “the American Constitutional order is secular in form but an outgrowth of a culture permeated by assumptions about human nature and moral truths born of Christianity.” The same could be said of the medieval European political order. The inquisition and crusades, the doctrine of the Jews negative witness and the atrocities from which these things arose were also “an outgrowth of a culture permeated by assumptions about human nature and the moral truths born of Christianity.” Surely the moral truths of Christianity have not changed? So which Christian moral truths are right, those born of the medieval church-state ones or the ones found in the modern secular state?

When European Christianity was monolithic in its Catholicism, it did not brook conversion or religious dissent lightly either. So we might ask the same question of Catholicism that you wish to ask of Islam: can it support pluralism when it is not a minority faith?

The American secularism lauded in this article can be –and often is – attributed to some nascent seed of secularism unearthed 1700 years after the composition of the relevant Christian scriptures, but such a claim seems anachronistic at best – it seems to suggest that no one properly understood the political consequences of Christ’s teaching until the mid 18th century. A far more plausible explanation is that a secular state was politically necessary given the diversity of belief already found in these fractious colonies, and the religious justifications for a secular state were readily found in the decidedly progressive, non-traditionalist, enlightenment mileau of its founders.

America’s secularism only indicates how marginalized sincere religious commitment has become. Orthodoxy – be it Christian or Islamic, does not necessarily regard diversity of belief (outside the accepted rhange) as insignificant or encouraged. But it’s worth pointing out in the context of this article that Islam’s historical record of tolerating dissent is far more commendable than Christianity’s. A quote from Mohammad Marmaduke Pickthal summarizes the matter well: “It was not until the Western nations broke away from their religious law that they became more tolerant; and it was only when the Muslims fell away from their religious law that they declined in tolerance”

So, I think Wessexman’s comments are relevant: this is not about Secular Christianity (can such a thing even be?) versus Islam; the tension is between secularism and orthodoxy. Christianity in America has largely ceded the field. And insofar as secularism is represented by America’s marginalization of religion, its opposition to Islam (real and imagined) and its moral depravity, it is hard to blame Muslims for their reluctance (real and imagined) to do likewise.

Mark,

Generally speaking it is groups within the different traditions. There are both Sunni and Shia extremists as well as moderates although Sunni extremism tends more towards individual terrorism whereas amongst Shia groups it tends to be more organized, but less mindlessly violent. There are exceptions to this however. The Ismailis, who are a shi’i tradition different from those ruling in Iran, for example, are basically pacifist although not quite to the degree of Quakers. The other area of the world that I am familiar with is the Balkans and there is a Shia tradition in the Balkans and Turkey known as Bekhtahism or Alevism who are also essentially pacifist. In the Balkans they are also strongly pro-American. For the record, Albania and Kosovo are functional democracies in countries which are overwhelmingly Muslim. Bosnia, while a democracy, is incredibly politically splintered and really only a Muslim plurality and not majority.

As to why certain groups are more pacifist, I don’t know if I can really answer that properly as I think many have different reasons. In some places it certainly has to do with intellectual engagement with Western thought. In Iran, for example, there is still a lot of interest and respect for philosophy and many in the movement I mentioned have studied philosophy at western universities. Shiism has also been historically pacifist, the revolution being the glaring exception and have been used to being an often oppressed minority whereas sunnism has almost no experience with such a situation. For the Islamilis and Bekhtashis I think it is mainly to do with having strong centralized leadership who has guided their communities in that direction. At root, however, I think the biggest factor is the havoc people see being caused by violent ideologues. When you see that you can’t help but think that this isn’t what God wants and this has sparked theological investigations that have born fruit.

Maybe one last theological point as to why the Shia tend to be more peaceful. In Shi’i belief one of the foundations of religion is justice and they believe that we can rationally determine what is and is not just. The majority of the Sunnis however developed the belief that we cannot determine justice rationally. If God decided to send all good people to hell and bad people to heaven that would be just. This is important because setting off a bomb amongst a crowd of innocent people is rationally unjust, but to Sunnis it doesn’t matter. If their religious leaders tell them that is what God wants, reason be damned. A minority of Sunnis reject this type of thought, but it is a major problem in sunnism.

I hope that was helpful and not more confusing.

Devin,

Honestly, I don’t think that you are going to get very far trying to understand the violent or peaceful reactions of Muslims in different parts of the world belonging to different sects by appeal to theological beliefs. Let’s remember MacIntyre here, we can’t explain phenomenon by appeal to beliefs abstracted from specific contexts.

E.g. Pacifism isn’t exactly going to gain much appeal in Iraq when its being bombed to smitherines and raped en masse. Appeal to intricacies of Sunni theology is hardly helpful here. The same can be said in Afghanistan and Palestine and elsewhere.

A distinction needs to be made between legitimate resistance and terrorism. This is hardly done and the absence of this distinction is what makes these discussions often pointless.

Yes there are certain differences between Shi’is and Sunnis and that does come through in different resistance movements. So yes, Shi’is have more of a religious hierarchy through the institutions of the marja’iyya, and largely as a result you don’t have splinter groups declaring jihad as you do in the Sunni world. In Sunni Islam you have no central authority especially since the Ottoman empire fell. Almost all of the governments in Arab world are seen to be devoid of legitimacy so you see a flowering of Sunni splinter groups declaring authority for themselves and acting on their own.

And one last point, you said the revolution in Iran was an exception to Shi’i pacifism. This is only half true. If you study the history of the revolution for the most part the resistance to the Shah was non-violent. Crowds of people poured into the street, unarmed, many of them in white burial shrouds. This was a symbolic act, it meant they were ready to sacrifice their lives. The shah’s troops often opened fire en masse. It wasn’t till a very late point that force entered the picture and on the whole the amount of violence related to the Iranian revolution cannot be compared to other modern revolutions, Russian, French etc. These points are often overlooked.

Several people here have posted that burning a Koran is an unchristian thing to do. Howard makes a very eloquent argument. But unchristian? How can you be so sure? The Koran specifically denies the divinity of Christ, and we know what our Lord said about the fate of people who deny Him. To destroy a work of heresy that leads souls away from Christ can certainly be considered a spiritual act of mercy. Tolerance of false belief was never a Christian virtue; there is a long history right back into Apostolic and Patristic times of destroying idols. Consider that no less than St. John Chrysostom led a group to destroy the Temple of Artemis, and there are many more such examples by saints. Consider that the evangelization of barbarian Europe was carried out by men like St. Boniface, who cut down the religious symbol Donar’s OAk of the pagans in Germany. As a Christian, I think one is on very shaky ground making a blanket statement that burning a Koran is unchristian.

It is just as likely that this is the kind of Christian witness that discomforts those believers who have become too cozy with the world.

(and the disclaimer: I am pretty far from the stripe of Christian this pastor is, far indeed, I am Catholic but nevertheless)

Steve,

You do make a good point in reminding us that we need to make sure our response to things like Quran burning is not a mere visceral reaction having more to do with the spirit of our times and society — in ours, this takes the form of being timid, unconfident in anything save uncertainty, morally indiscriminate, effetely tolerant — than with our own honest moral discernment rooted firmly in a sound and confident narrative/tradition.

But we must consider the context in which the action is occurring. Rev. Jones’ act is not a prophetic one. It is purely political in nature and at its heart is a dark shroud of fear and ignorance. Judging by his own words and volatile performance, Jones has made it fairly clear that he doesn’t have the courage to tear down false idols because he doesn’t have the humbled wisdom to raise a monument of Truth in their place. We cannot overlook the intention behind an act, the meaning the actor has imbued it with. When we look behind pastor Jones’ planned Quran burning we find what amounts to a temper tantrum, surrounded by lies to the witnessing community about conversations that have never actually happened and a swath of fictitious grandeur. The critical difference between the Saints and church’s like pastor Jones is that the Saints were not acting out of fear and timidity. They marched into pagan squares and proclaimed truth. And, in the midst thereof, exuding justice, they exhibited love, humility and grace.

I would grant more legitimacy to such an argument if more church’s were making similar statements to the real threat of our age: not Islam, but modern secularism. The idol we need be concerned with right now is Mammon, not Muhammad.

Steve,

Thanks for the comments & the stimulus to brush up on some history.

I base my surety on the pattern I observe in the New Testament.

You speak of St. Chrysostom, leading in the destruction of the Temple to Artemis. Had I been present I imagine that I would have been pleased. Perhaps the difference in Strategy had to do with demographics. In the Apostle Paul’s day, Christians were an infinitesimal minority in Ephesus. In St. Chrysostom’s time they were a force to be reckoned with. I don’t, however see Paul as being cowardly, “or cozy with the world.” Had he concluded that God’s method for saving the people of Ephesus was the destruction of this pagan temple, I think we would have seen him with his hammer.

The fact that Christians in the time of Chrysostom were able to tear down the temple was because of the success of the method that the Apostle did follow, “we persuade men.” (2 Cor. 5:11)

I’m not sure if I would describe my argument as “very eloquent,” but thanks. Eloquent or not, I did finish with an appeal, not to avoid risk, but to do right.

You are right; we do occupy different stripes in the cloth of Christianity. I suspect that our choice of material from which to argue is a result of that. I have respect for Christian leaders who came after the completion of the New Testament. I do not hold them in same esteem and authority as you and your fellow Catholics. That, however, is a different post.

There is a practical consideration:

If I thought that a pastor in America burning one, a thousand, or a million copies of the Qur’an would lessen the impact of a book that “leads souls away from Christ,” I might be more willing to consider the burning of a false Holy book as an act of mercy. The fact is, such acts, by those in the West, who are (at the very least) thought to be Christians by Muslims only serve to make it more difficult for the Christians in lands where they are a minority to engage their neighbors in profitable conversation, that might lead to conversion.

“The idol we need be concerned with right now is Mammon, not Muhammad.”

AMEN!

For those of you from other stripes of Christianity, that means I very much agree.

“Wessexman,

As long as the political reality is the modern, pluralist nation state, I’m not sure how we can avoid incorporating some modern liberal notions into the discussion. Can you see a way beyond that? I’m perfectly happy debating the relative merits of the modern nation state, but in terms of our current situation, that’s what we are dealing with.”

I just meant that as a Christian traditionalist I’m not much interested in plural or secular or multicultural societies and so on myself.

“point about the nature of fundamentalism is a good one. How is the debate changed when the categories of fundamentalism and ideology are introduced?”

Well it does allow us to realise there is a difference between Saudi Arabia or Iran and traditional Islam. Ultimately there is much of a difference between traditionalist Islam and traditionalist Christianity at the level we are speaking of.

Darn, yet again I made a typo. I meant there isn’t much of a difference between traditional Islam and traditional Christianity at the level we are speaking of. They’re both opposed to secularism and modernism and should focus on these rather than attacking each other(not that I’m suggesting multiculturalism or plural societies is a good thing or even workable.).

Mark, of your two questions the first (is it correct to equate Islam with 9/11?) is the more important. My understanding, as an outsider and not a practitioner of the faith, is that it is a profound misunderstanding of Islamic teachings to make this association. The word Islam literally means “peace”. In the same way that “God is love” in Christianity, one could say that “God is peace” in Islam. Islam represents a path of morality and compassion. Tenets of the Islamic faith — such as the concept of jihad — are misinterpreted as endorsing war. However, as I understand it, jihad is best translated as “struggle” and refers primarily to the struggle to bend “self” to the service of God and the path of compassion.

Since you have this question (and because I am not a good authority) you might find it helpful to look into the teachings of Islam on your own (just by way of developing an unuderstanding — I am certainly not recommending that you look into the teachings as a personal path). There are a few options for doing this. The best would be to have a conversation with a friend who you respect who is a Muslim. They may or may not be willing to engage you in this discussion depending on how your motives are perceived. Books are good as well. Karen Armstrong is a former Catholic nun who has written popular books on several of the great religions. Her books tend to be accessible, respectful and objective.

The problem, of course, is — as you note — that as with all religions the teachings are interpreted in ways that are inconsistent with the core vision of the faith. So a teaching of Islam, such as the prohibition on images of God, can be both an inspiration for the architechture of the Taj Mahal (arguably the most beautiful building in the world) and a justification for the destruction of great works of art of other religions (such as the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhist statues). Al-Qaeda is essentially a political organization that seeks the liberation of the Arabian peninsula from the influence of Western governments. It is not an Islamic organization. The use of religious rhetoric by Al-Qaeda is a tactic and a perversion of the faith.

The Christian religion, of course, is not exempt from misinterpretation either. Many wars have been fought in the name of Christ — from the Crusades through to wars of modern times. It is my view that, without exception, to the extent these wars are fought in the name of Christ, they are perversions of Christ’s teachings.

So, because the association of Islam and 9/11 is a false association, opposition to a Muslim community center two blocks away from the World trade center site is based on emotion and a lack of understanding. However, as I said, ignorance needs to be respected (or the possibility of communication needs to be preserved). That may require a dialogue and maybe even a compromise.

Jim,

I recommend not relying on Karen Armstrong, not for learning about Christianity and definitely not for Islam. Her books are garbage, by and large.

Tenets of the Islamic faith — such as the concept of jihad — are misinterpreted as endorsing war. However, as I understand it, jihad is best translated as “struggle” and refers primarily to the struggle to bend “self” to the service of God and the path of compassion.

Look, Mohammad was an actual, honest to goodness, warlord. He rode at the head of conquering armies, planned and executed military campaigns – he was a spectacularly effective commander. It is objective, historical fact that the spread of Islam during his lifetime (and beyond) came at the edge of a sword, including the one he actually carried. I think this puts some context to the meaning of jihad and whether it endorses war.

This is pretty basic stuff, basic facts about the founder and foundation of Islam. Be careful about making accusations of ignorance and lack of understanding.

I stand by what I said. There is ignorance on both sides of this debate. And it is quite dangerous. When we conceive of the beliefs of another religion in a sweeping and simplistic fashion (as you have done) and make accusations that they represent aggression and evil (which is perhaps implicit in what you say), it is a short step to resolving to destroy the other.

The irony is that some forms of Christianity and Islam have too much in common in this regard.

So, I would ask you to be careful — for all of our sakes.

The irony is that some forms of Christianity and Islam have too much in common in this regard.

I can’t emphasize this enough.

I suspect that Christian and Islamic fundamentalism have a lot in common, not the least of which is that Wahabism and Christian fundamentalism spring up at about the same time. Fundamentalism is an accommodation to Enlightenment individualism, hence the concentration on “personal interpretation” and the non-biblical catch phrase, “Jesus Christ is my personal savior.” The communal salvation given by the Mass in Catholicism, Orthodoxy, and sacramental Protestantism gives way to a pure religious individualism, a kind of sacred “every man for himself.” It is the self-interest of Jeremy Bentham projected into the ultimate realm, and religion becomes the ultimate utility in a utilitarian polity.

I do not know enough of Islam to say if there are parallels; however, I would not be surprised if it were so, since similar causes tend to have similar effects, even on different groups.

I wanted to share with you guys the statement of Ayatullah Sistani regarding the Qur’an burning incident. This is a man considered by many Shi’a Muslims to be the highest religious religious authority. Take note of his response.

In The Name of Allah The Compassionate, Most Merciful

The media is covering a U.S priest’s insistence on burning copies of the Holy Quran as an expression of his hatred for the Islamic religion.

This shameful act is inconsistent with the duties of religious and spiritual leaders –to establish the values of love and peaceful coexistence based on observing the rights and mutual respect between different religions, and intellectual approaches.

The concerned parties in the United States are invited to act to prevent this abominable act which, if occurs, will have adverse consequences and may have dangerous repercussions.

Respect for freedom of expression does not justify allowing such shameful acts, which represent a blatant attack on other peoples’ beliefs and their sanctities leading to more tension, conflict and violence.

The religious Marja’iya strongly condemns the attack on the great Qur’an and emphasizes the necessity of preventing its occurrence whilst stressing on Muslims, wherever they are, to exercise the highest degree of self-restraint and not to show what is harmful to followers of Christian churches remembering the saying of the Almighty:

{O you who believe, act steadfast towards God, as just witnesses; and do not let the ill-will of any folk incriminate you so that you swerve from dealing justly. Be just: that is nearest to heedfulness; and heed God [alone]. God is informed about what you do} – Holy Quran chapter 5, verse 8.

The Office of H. E. Sayyid Seestani (long may he live) – Najaf

29 Ramadhan 1431H

It can be found here: http://www.najaf.org/all/view.php?l=ENG&c=statement&t=STA&i=90910

By what authority would one claim that the interpretation of “violent Islamic extremists” isn’t authoritative, binding, traditional or correct?

Doesn’t Ayatullah Sistani say apostates should be punished with death?

If you wish to learn about Islam I recommend the works of Frithjof Schuon on Islam.

http://worldwisdom.com/public/products/0-941532-24-0_Understanding_Islam.aspx?ID=28

“Islam is the meeting between God as such and man as such…. Islam confronts what is immutable in God with what is permanent in man.”

John Medaille is right about fundamentalism. It is modernist to its core. It is basically about turning a traditional religion into an ideology like Marxism so that it is all boiled down to a limited amount of narrow and literal readings of one or two texts but of course sprouts off into all sorts of individuals nuances because of this ideological narrowness, like the ideologies of Marxism or Liberalism.

That lady cartoonist who did the Everybody Draw Mohammad day? She’s going into witness protection, getting a new identity. Thanks Muslims!

http://www.seattleweekly.com/2010-09-15/news/on-the-advice-of-the-fbi-cartoonist-molly-norris-disappears-from-view/

Almost makes a man want to burn a Koran.

The primary concern of we as Christians should be ridding the Church of its own false idols so that it may cast a purer light unto the world. This is how the body is fortified and made to stand firm against what it keenly perceives to be the false and treacherous claims of men. Without this, the faculty of such vision is itself lost. This is exactly the practice we rally against when we begin to slip into idle condemnation. It is distinctional in its partiality, whereas we are called to be wholistic and relational. I see no scriptural evidence that all men were expected to enter into the Church, and if this much is true, then it is safe to presume that we are to recognize ourselves as living in a world that is not uniformly reconciled with its Creator, and will, more than likely, be this way for quite some time. We speak to such others with the expectation that we will be having to remain their neighbors.

We know the dangers facing lost sheep, and it is antithetical to our position as Christians to ostracize the lost, for beyond its simple selfish vacuity, it does nothing but entrench division and postpone the unification of Creation and Creator. We need not relish in our ability to recognize the sin in others with taunting remarks and self-praise, for this merely leads to hubris and pride, and a failure to recognize how fare we ourselves have yet to go. If anything, we should be led to love those others even more, to wish to understand them — which is another way of saying to draw them near. Strong criticism can itself be a form of loving humility, for it lies prostrate before Truth, and can’t but deny all which speak against it. There is a subtle yet perceptible difference between this and prideful antagonism, whether in the form of burning Qurans or jeering with condescension those who revere it.

John Medaille makes an interesting point about Christian Fundamentalism.

My brother, a Presbyterian minister, notes that fundamentalist Christians cite to the Gospel of John for the proposition that belief in Jesus Christ is the basis of salvation. However, in his view, an approach that puts too much emphasis on belief falls into theologocal error. Belief becomes an act that earns a believer admission to heaven. It is a mental act, but it is a version of a theology that holds that salvation can be achieved through “works” and ignores the concept of grace — that salvation is not a personal achievement but miracle of the grace of God. And the error in an odd way can be the basis for Fundamentalists repeatedly to fall into sin — so that they can experience form time to time the “high” that comes from renewing their belief.

I have to point out that my brother says this in a kind way — like you would talk about a brother with crazy ideas.

I have been trying to stay out of this, but alas I am succumbing to temptation.

I guess I’m thinking that if we have as much trouble understanding Islam as some of the commenters have understanding Christian Fundamentalism then the ignorance, that has been mentioned here runs deeper than we realize.

For one thing you need to understand that Christian Fundamentalism has a definite historic definition. Usually those who hang out on this porch are pretty careful about history. I am surprised that in comments about Christian Fundamentalism the history–fairly recent and well publicized has been largely ignored. Too often, here and in other discussions, the word is used without any reference to its antecedents.

I know that words change over time. In many ways “Fundamentalism” has been hijacked. Many of us who are Fundamentalists in the historic sense generally don’t use the word to describe ourselves, because it has become associated with extremism, lack of thinking, bigotry, and other negative concepts in the minds of many.

I only have a minute–I have to look over my list of Bible passages to which my Fundamentalist training restricts me, so that I can come up with some personal interpretations and non-biblical catch phrases for Sunday’s sermon (For those of you who think anyone who would in any way associate himself with a Fundamentalist title is incapable of sarcasm, that was an attempt at such.) so I’ll just give a few quick bullet-points.

• Yes, Fundamentalists do believe that that salvation is a personal matter. This is a theological point that they share with Evangelicals in general. The Biblical evidence for this concept is found outside of the Gospel of John.

* Included in the few scriptures that we do teach is Romans 6:1. I can’t speak for the motivations/errors of every Christian leader—Fundamentalist or otherwise who falls into sin—I do know that in all my association with Fundamentalists over a lifetime of ministry, I have never heard anything that would indicate that “that salvation [being] not a personal achievement but [a] miracle of the grace of God. . . . [would] . . . be the basis for Fundamentalists repeatedly . . . fall[ing] into sin.” In fact in expositions of Romans I have often heard such reasoning condemned.

* Many Fundamentalists are dedicated to a book by book exposition of Scripture. Their (our) belief system is not the result of the study of a one or two texts (Unless by “text” you mean the Bible.

• Because a dog was born on the same day that a table was made, and each has four legs, does not make them similar in ways beyond that.

• Fundamentalism historically was a reaction against trends in Theology that were associated with modernism. All five of what became known as the Fundamentals (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fundamentalist I normally would not use an article from Wikipedia, but a quick scan of this one shows that it has the facts pretty much right in a compact article. I can’t vouch for the links.) are miraculous in nature. Hardly in sync with modernism. One of the consistent battles of Fundamentalism is opposition to Evolution, again hardly a modern stand. One of the criticisms of Fundamentalism—often a just one (see some articles on my blog)—is that Fundamentalism is opposed to modern (used in both senses of the word) expressions of culture. Perhaps most anti-modern of Fundamentalism’s tenets is much of Fundamentalism holds to a dispensational system of understanding Scripture. Both dispensational and nondispensational Fundamentalists believe in the depravity of man. Man is not good–left to himself and his devices he will not make a better world. Included in the texts from which we wrest personal interpretations is the book of Judges. Inherent in these views is a rejection of any ability on man’s part to make this world better. Entropy is the operating tendency. In an ironic way Fundamentalists may have come to some of the same errors as Modernists, but claiming it is “modernist to its core”? That is Fundamentally wrong.

Howard I had a reply but I don’t think this is really the place for such discussions. I do think fundamentalism is very modernist in its thought processes but I don’t want to cast out sincere Christians nor to spend much time infighting among genuine believers on a site like this.

Peace.

Wessexman,

Thanks for the pronouncement of peace.

It is sincerely reciprocated.

I’m increasingly frustrated with the bizarre conflation of Christianity and secularism.

I understand that it allows Christians to set up a very effective straw man argument whereby Christianity is essentially tolerant and modern, and Islam is essentially intolerant and backwards, but in the end, it’s still just a straw man.

And I’m even more frustrated with its appearance on FPR. I expected a better sense of history and more respect for traditional understandings of religion. I did not expect to see such an uncritical equivocation between Christianity and modernist enlightenment philosophy.

To return to Mark’s basic question, “…is there a peaceful core to Islam that allows it to co-exist in a pluralistic society? …is [this] possible when Islam is the majority religion and when Muslims are in charge politically. Despite other problems, Christianity has shown itself capable of doing this. I am [making a claim] merely about the possibilities of each to thrive in a pluralistic society where basic freedoms of expression and religious belief are respected.”

The short answer is yes. The proof is the history of medieval Islam, where Christians, Jews, Zoroastrians and Hindus, as well as minority sects of Islam were allowed to practice their religion because Islamic law safeguarded their rights.

The same cannot be said of medieval Christianity or the rule of medieval Christians. When Christians ruled Europe, “basic freedoms of expression and religious belief” were not “respected.” That they are today is only an indication that secularism dominates, not Christianity. Secularism respects those freedoms, not orthodox Christian doctrine.

Therefore, I reject Mark’s claim that Christianity has proven itself capable of co-existing peacefully with minorities when it is the dominant religion. The U.S. and Europe do not support Mark’s claim for this reason: these are not lands in which Christianity dominates; secularism dominates. It should be obvious that the two are not the same.

If by “dominant religion” we only mean that the majority of people self-identify as Christians, well, that seems to render the claim vacuous due to the absence of any clear definition of what it means to be “Christian,” and the absence of Christian doctrine being enshrined as the foundation of law. This latter point seems essential to the dominance of a religion: the religion rules; peoples lives, the laws by which they live, are governed by religion.

When we look at times and places where Christianity did dominate, we do not see proof that it can co-exist peacefully with minority religions. There were no masajid in Medieval Europe. There was, however a reconquista and a subsequent inquisition. When we look at times and places where Islam did dominate and the societies were governed by Sharia, we see that minority communities were allowed to exist and manage their own affairs without the interference of the Islamic state. (Pickthal’s essay, “Tolerance in Islam” contains some lively examples.) And, notably, when Islam spread to the north and into the Levant, there was nothing comparable to the reconquista and its subsequent atrocities.

Given Islam’s recognition of the rights of religious minorities (enshrined in the much-maligned Sharia), and the absence of any such recognition in Christianity, I would prefer to live under a land dominated by Islam than by Christianity. And this seems like a more equitable hypothetical choice than being asked to choose between Islam and secularism.

The bottom line: it is absurd to compare Islamic belief, which is inherently religious, with American law, which is inherently secular. A more fair – and illustrative – comparison is to compare Islamic law and its treatment of religious minorities with Christian law and its treatment of minorities.

Samuel,