[Cross-posted to In Medias Res]

[Cross-posted to In Medias Res]

Would I read Charlie Hebdo? (Assuming I could read French, that is.) Would I want anyone in my family to read it? Would I want it to be available at my daughters’ elementary school library, or at the high school library, or on sale at my neighborhood QuikTrip store? Those questions aren’t all the same, obviously–but neither are they, I think, completely unrelated to each other either.

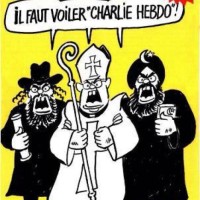

As for me personally, well, I am a regular reader of The Onion. And Monty Python and David Letterman have been pretty central to the formation of my often sarcastic, mocking, absurdist, even cynical take on the world. On the other hand, I’ve never really taken to South Park, and I’ve never been more than ambivalent about the really vicious–however darkly brilliant–traditions of comedy satire out there. (Bill Hicks, take a posthumous bow.) And Charlie Hebdo’s over-the-top anti-clericalism (just see here) certainly seems to fit in that category. (The cartoon above has French Jews, Catholics, and Muslim all shouting “Charlie Hebdo must be veiled!,” an obvious reference to the ongoing controversy over laws banning Islamic scarves and facial veils in public in France.) I suppose I content myself with watching the Life of Brian in part by reminding myself, on some level (as the Pythons themselves always insisted!), that the film was heretical, not blasphemous. That’s not an easy line to draw, obviously, but I think it’s worth drawing. To be heretical is to challenge or mock an orthodoxy, an established understanding, an institutionalized structure of one’s faith and way of life; to be blasphemous is to mock or attack the point or object of that faith or understanding or way of life itself. And assuming you take both 1) religion and 2) the obviously social lived reality of cultural and community formation seriously, the latter is a much greater problem than the former. So figuring out how to distinguish between them–and also, though certainly not in the same way or to the same degree, given the different contexts involved, for my family and my neighborhood–is worth doing, however uncomfortable doing so in a liberal society may be.

Of course, when you’re faced with horrors like Wednesday’s massacre in Paris, that discomfort also feels pretty cheap. When three men take it upon themselves to murder a dozen others because the words spoken by those others, and the cartoons they drew, seemed blasphemous to them and/or their community (or, as some have smartly suggested, when terrorists see a way to ramp up amongst the French public the sort of provocative and defensive discussions of “blasphemy” which might well rebound to their benefit), the notion of clarifying one’s anti-liberalism and explaining why and how you think some speech is virtuous and some simply isn’t may well be probably pointless. Stand with the cartoonists, stand with the blasphemers! In one of his best columns in a long time, Ross Douthat makes this point very well:

[W]e are not in a vacuum. We are in a situation where…the kind of blasphemy that Charlie Hebdo engaged in had deadly consequences, as everyone knew it could…and that kind of blasphemy is precisely the kind that needs to be defended, because it’s the kind that clearly serves a free society’s greater good. If a large enough group of someones is willing to kill you for saying something, then it’s something that almost certainly needs to be said, because otherwise the violent have veto power over liberal civilization, and when that scenario obtains it isn’t really a liberal civilization any more. Again, liberalism doesn’t depend on everyone offending everyone else all the time, and it’s okay to prefer a society where offense for its own sake is limited rather than pervasive. But when offenses are policed by murder, that’s when we need more of them, not less, because the murderers cannot be allowed for a single moment to think that their strategy can succeed.

There’s nothing I can think to add or take away from that statement. I dislike liberal individualism, and am deeply suspicious of our (I think somewhat ridiculous) idolization of free speech. When the important liberal principle of respecting the profound plurality which modern subjectivity and technology and liberty has enabled to develop across the globe becomes (or is twisted into) a determination to stifle or discredit any attempt by any group of people–a family, a church, a neighborhood, a polity–to establish norms which sometimes (not always, but sometimes, as the democratic debate may make appropriate) may be reflected in law, then the very possibility of treating civility and community as the robust concepts they in truth are and deserve to be simply goes out the window. But none to that is relevant to what happened in Paris. Terroristic acts of violence are not in any possible way comparable to the introduction of democratically determined rules of civil society. Offensive speech, even blasphemy, becomes–as Christopher Hitchens, complete ass though he was, correctly argued long ago–a positive good in a situation when someone chooses to use violence to shortcut the process by which religiously pluralistic societies get democratically nudged in one direction of another through discourse and the collective decisions of thousands of individuals within their local groups. That gives anti-liberals a veto power that we shouldn’t want anyone to have, or else freedom is done for.

One response to that, though, is to remember the argument from just a little more than a decade ago, at the time of the violence which followed the publication of blasphemous, anti-Muslim cartoons in a Danish newspaper (cartoons which Charlie Hebdo happily reprinted!). The claim made then, in essence, was that Muslims in Western Europe were living in a condition of having already had their faith and way of life “vetoed,” and thus care must be taken in dismissively telling Muslim fundamentalists to eschew violence and trust in “the process.” On a certain level this was, obviously, nonsense (there were numerous robust and well-established Islamic institutions throughout Europe a decade ago, and are even more today), but it wasn’t utterly groundless nonsense. Anti-Islamic sentiment and outright paranoia are realities throughout the continent. The nations of Western Europe–none more so than France!–have a complicated collective relationship with their sectarian Christian pasts, and the result is a huge amount of inconsistency and frustration in how they are to accept the reality of their internal cultural transformation. (The historian David A. Bell talks at length in an old essay here about the failure of France to extend its Enlightenment ideal of republican assimilation, after so many–relative–successes throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries–to the largely Muslim immigrants who came to live within its borders in the years following WWII and continuing until today; some comments of mine about the essay are here.) So perhaps our thinking about whether we should embrace, or at least be willing to defend in the face of violence, an offensive and blasphemous publication like Charlie Hebdo should be done with a consciousness of how very Western, Christian, and liberal the mental processes by which we distinguish between merely “heretical” offensive speech, and that speech of a worse–for a faithful Muslim, anyway–kind.

The fact that we spent more than a decade (and, to a degree, still are) trapped with the “war on terror” discourse makes the ability of us to think carefully about these levels and contexts of appropriate speech doubly difficult; because the rubber so often meets the road in the case of depictions of the Prophet Muhammad or other particulars of the Muslim faith in secular, Western venues, almost every attempt to get clear on these important issues gets tangled up in the same old “clash of civilization” arguments which dominated our thinking for far too long. I contributed my part, to be sure. In long debates between those who insisted that the respect of individual liberty necessitated a rigorously neutral–and thus non-line-drawing–public square, others tried to enlist the kind of limited, carefully anti-liberal distinctions I’m talking about here into a larger meta-liberal project. Defenders of the idea of America taking on the responsibility of a liberal imperialist project in the Middle East–bringing democracy to Iraq!–would suggest that America speaking out against tendency of (Western European) secular society to engage in (often anti-Muslim) blasphemy would be a way of lessening fundamentalist suspicion of American modernity, and help us find allies.

This argument was, as they say, too clever by half; my friend Damon Linker referred to it as a “sentimental civic-religious-providential amalgam of America, Christianity, and Democracy,” and while I tried to rescue the idea at the time, I can now see that Damon was right. Not to impose too many binaries upon these complicated debates, but you really probably can’t fully align these two different perceptions of the relationship between individual expression and freedom, and certainly not under the aegis of some oppressive civilizational narrative. If, in the end, you’re persuaded by those arguments or those experiences which lead you to hold your neighborhood, with all its cultural norms and social structures, as that which really matters most, then getting into the thick of figuring out just when and where and to what degree you’re going to be content with contemptuous and blasphemous–even if funny!–speech like Charlie Hebdo‘s in the liberal society you live in is just going to have to be your anti-liberal responsibility. And if you’re not so persuaded–if you really don’t, contrary to what I wrote at the beginning of this post, make “religion and the obviously social lived reality of cultural and community formation” your priority, for whatever reason–then you’re justified in looking at the rest of us suspiciously. Since, of course, depending on whatever democratic changes and cultural contexts may come, it might be your blasphemy which we start trying to dissect next.

I don’t imagine there’s any likelihood that this particular debate about liberty and community will ever be fully resolved so long as the modern epoch continues. In the meantime, for those liberals who are–reasonably, if not, I think, fully justly–worried that those of us who are appalled by these attacks and yet still want to say something like “I’m not defending the terrorists, but Charlie Hebdo was often indefensibly gross” will turn out to be fair-weather friends, I’ll just point to those many people who have, and continue to, make these distinctions carefully and well. And for those whose anti-liberalism carries them all the way over to violent religious fundamentalism, whether Muslim or otherwise, all I can say: don’t confuse a willingness to attend to the particulars of one’s community with the liberalism of fools.

Localism means above all that each locality chooses its own rules. Since 1989 the US has been breaking all borders and walls, imposing its own Establishment rules by massive lethal force on parts of the world where those rules make no sense. (Those rules make no sense to the ordinary American either, but we’re too firmly enslaved to do anything about it.)

We shouldn’t be so surprised to find that foreigners don’t like our rules, and we especially shouldn’t be surprised when foreigners attack a rigidly orthodox propaganda outlet that has been helping to spread those rules.

There’s nothing ‘heretical’ about any of the propaganda outlets you mentioned. All of them agree strictly and precisely with the doctrines propounded by Bush, Obama, Cameron, Merkel, Hollande, etc. Those periodicals and TV shows pretend to be ‘rebellious’ against Soviet doctrine, just as Krokodil pretended to be ‘rebellious’ against Soviet doctrine in an era when Soviet doctrine had a different geographical center.

I have a minor comment on your insightful essay.

You refer to “idolization of free speech”. I like this phrase. Free speech is often misunderstood as a policy that treats disparate views as all being equal. “Everyone is entitled to their opinion”, after all. But this is a corruption of the meaning of free speech.

In fact, free speech has two separate meanings. The first is a limitation on government action. The First Amendment cannot be understood without understanding the necessity for government action to trigger First Amendment rights. Under the U.S. constitution, as a private citizen I am entitled to argue against, deride, ridicule, even shout down the speaker of views I oppose. In fact, the government can’t stop me from doing this because my speech is free. So, there is absolutely no requirement that “we should embrace, or at least be willing to defend in the face of violence, an offensive or blasphemous publication like Charlie Hebdo”. In fact, if I decide to cheer the violent and criminal acts of the terrorists who attacked and killed the Charlie Hebdo journalists, that speech is protected by the First Amendment.

The second meaning of free speech is the view that private citizens should, as a guideline and as a matter of decorum in a civil society, tolerate others’ free speech or, at least, allow an argument to be made before it is ridiculed and rejected. This meaning of free speech is best exemplified by policies favoring academic freedom in private universities (public universities as arms of the government necessarily must grapple with both meanings of free speech). However, it is important to understand that this second meaning of free speech also does not require an embracing or acceptance of others’ views. In fact, it requires just the opposite — critical analysis and rejection of wrong views.

Viewed this way, we don’t need to accept or like or even tolerate either Charlie Hebdo’s views or the views of Islamist extremists. We just need to enforce the criminal law.

These Charlie guys are a lot more sympathetic in theory than in practice. Yay, free speech! Yay, satire! Yay, speaking truth to power!

Hold on a second, do they? Do they ever question the radical secularization of society in France, and whether it tramples on individual rights? My impression is absolutely not. After all, as we know, in France “equality” may come second in their silly national slogan but it’s pretty much all that matters, as defined by the state with no regard for “liberty.” That total power is not one they “speak truth to” from anything I’ve ever heard.

I don’t much mind their blasphemy, because blasphemy is, above all, BORING in the modern world. There’s nothing offensive about priests that can be said that wasn’t said with more cleverness, wit, and righteous fury a thousand years ago. But that cartoon you include in this story really gets me, because it’s just so stupid and insincere, and that I just can’t tolerate. I guarantee you that they don’t actually, in their hearts, believe their is an equivalence in how they were viewed by their critics who were Jewish, Christian, and Muslim. I guarantee you they felt absolutely no fear from rabbis or priests, but that imams petrified them, and that if you were to ask them, they would acknowledge that the odds corresponding to them being murdered by one of those groups were 0, 0, and 100, respectively.

The fact is that Charlie is a perfect representative of the dominant force of the last half-century–the teenager. Too old to be a child, but unwilling or unable to behave as an adult (naturally, blame must be placed on adults for refusing to enforce norms). Of course, if I bring my child to a fancy restaurant and they have a temper tantrum and start throwing their food, the diners at the next table don’t get to shoot them, and no one would argue that they were justified in doing so, nor would I be called to justify my children’s behavior. Children are preferable to savages, naturally, or so I would have thought we could all agree.

“Defenders of the idea of America taking on the responsibility of a liberal imperialist project in the Middle East–bringing democracy to Iraq!–would suggest that America speaking out against tendency of (Western European) secular society to engage in (often anti-Muslim) blasphemy would be a way of lessening fundamentalist suspicion of American modernity, and help us find allies.”

Um, you do realize that the folks saying that Charlie and its ilk should just shut up and not offend delicate Muslim sensibilities are in fact 99% of the time the biggest opponents of US involvement in Iraq and the Middle East, right? Barack Obama himself. The New York Times. Etc. This is not in fact the fault of George Bush and Dick Cheney, and trying to jam it into that shape is asinine.

Brian, I think you are wrong on two points. First, it is astonishing to read that Barack Obama is “[one of] the biggest opponents of US involvement in Iraq and the Middle East.” Obama has expanded drone warfare and expanded US military intervention abroad — differing only from George Bush in his willingness to condone torture.

Second, this latest manifestation of terrorism is a direct result of Bush / Cheney “anti-terrorism” policies. One of the shooters at the Charlie Hebdo offices was radicalized by reports of US activities in the Abu Graib prison just as ISIS with its executions of Western prisoners in orange jump suits is a direct result of Bush / Cheney’s policies displacing Sunni Iraqis from power in a shockingly naive and ignorant effort to promote democracy and American “values” and hegemony.

Jim: I don’t debate foreign policy anymore. I’ll just clarify that by “this” I was referring to the issue in the quote I excerpted–the notion that Westerners should criticize critics of Islamism in order to placate them and avoid just this sort of terror.

Many fine comments here! I’m sorry I haven’t been able to respond sooner, but here are a few thoughts about the above:

Polistra,

We shouldn’t be so surprised to find that foreigners don’t like our rules, and we especially shouldn’t be surprised when foreigners attack a rigidly orthodox propaganda outlet that has been helping to spread those rules. There’s nothing ‘heretical’ about any of the propaganda outlets you mentioned. All of them agree strictly and precisely with the doctrines propounded by Bush, Obama, Cameron, Merkel, Hollande, etc.

I suspect that we’d be able to agree a great deal in condemning the sort of secular globalization which media outlets around the world–including Charlie Hebdo— obviously are complicit in, but still, something about how you frame this here seems a little too pat to me. It may not speak to your general point, but in the specific case of this attack, for example, does it really make sense to speak of Islamic fundamentalists as “foreigners”? These terrorists were French citizens; they spoke French fluently, and had lived in France all their lives. How does it help our understanding of how a regularly blaspheming publication infuriated (or at least presented itself as a strategically helpful target for infuriation) to characterize French Muslims of Algerian descent as “foreign” to France or the West in general?

JimWilton,

there is absolutely no requirement that “we should embrace, or at least be willing to defend in the face of violence, an offensive or blasphemous publication like Charlie Hebdo”. In fact, if I decide to cheer the violent and criminal acts of the terrorists who attacked and killed the Charlie Hebdo journalists, that speech is protected by the First Amendment.

I agree that there is no “requirement” that we regard the offenses purveyed by Charlie Hebdo as the sort of positive good which Douthat presented them as–and, of course, to condemn it and celebrate instead the attack upon it is nonetheless to be protected in a liberal society as well. But Douthat, and I (though it a slightly different way), were talking about how those who wish to provide support to at least some of the fundamental goods which a liberal society provides–First Amendment protections being a major example of such–ought to respond to the presence in society of those who actually would carry out attacks like this: people who would exercise the ultimate veto power by threatening terror and murder against those who would speak out. One way to let such people know where liberal sympathies lie is to give blasphemy a small, but celebrated, space among us.

Brian,

The fact is that Charlie is a perfect representative of the dominant force of the last half-century–the teenager. Too old to be a child, but unwilling or unable to behave as an adult (naturally, blame must be placed on adults for refusing to enforce norms)….Children are preferable to savages, naturally, or so I would have thought we could all agree.

I really like that way of putting it, Brian. Blasphemy and mockery are things that children do–a common enough and probably sometimes even defensible action (we’re all a little childish sometimes, and only the most humorless of persons would insist that naughty bathroom or bedroom humor is never, ever funny, under any circumstances whatsoever), and the sort of thing that has to be defended against those who would savagely disregard the basic fundamentals of liberal civilization, but still, pretty childish all the same.

I am philo-Islamic (Shia branch anyway) however I think the only lesson here is not a free-speech lesson but rather an anti-immigration lesson. You know what? There are already lands set-up and ready-to-go for Muslims. Use them!!

It has probably already been noted, but I think society used to smooth out cultural extremes like Charlie Hedbo, but now they seem to be portrayed as the norm and those of use I would consider part of the norm, and I use the broadest possible brush as I write this, watch from the sidelines with amazement.

I lump the Hedbo folks in with Las Vegas. I’ve been there for conventions and can’t wait to leave even before the plane rolls up to the terminal. It represents much of what I find despicable about American culture, and yet. . .and yet. . . the contrary farmer in me is glad there is a place for a place like that in this country, and I support Charlie for similar reasons, though I would never bother buying a copy.

[…] comments that Muslims are fair game, it bears reminding that Charlie Hebdo has been known for equal-opportunity mockery of religion in […]

Comments are closed.