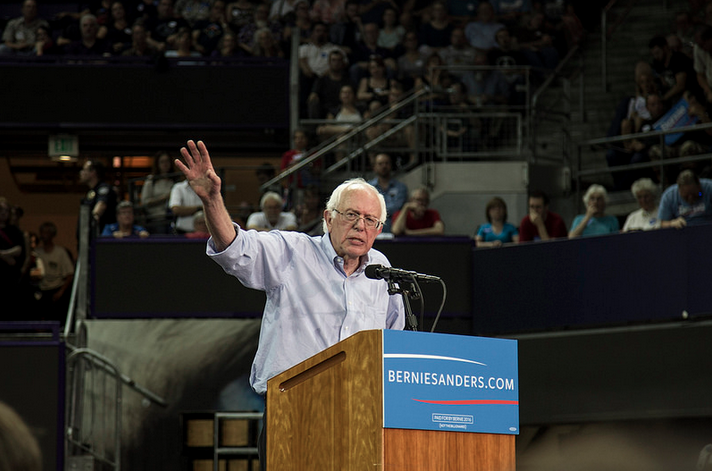

Last month, the Washington Examiner upbraided two Democratic contenders for the Presidency, Bernie Sanders and Martin O’Malley, for wanting to “turn back the clock.” It seems like a rather strange assertion to make, Democrats tending to think of themselves as progressive. The proposal for which they’d earned the charge of being backward-looking was, in fact, the reinstatement of the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act aimed at reregulating the banking system and possibly undoing the poisonous effects of those ‘too big to fail.’

Shortly afterward, Jeremy Corbyn – the left-leaning, anti-war MP currently running for the Labour leadership – was accused of trying to ‘cling to the past’ by his own party-mates and competitors for the leadership. Again, the reactionary proposal which earned him such scorn was not anything which can remotely be regarded as in any sense right-leaning: the anachronism of which he stands accused is that of reaffirming public ownership of, among other things, the Royal Mail, the railway system and Britain’s energy infrastructure.

It appears strange that a conservative would attack candidates to their left – O’Malley, Sanders and Corbyn – for being reactionary in some way. However, it is interesting to note that these candidates (in an American context, at least) are appealing, albeit rather haphazardly and from within institutions where their views are marginal, to an idiosyncratically conservative set of perspectives and policy priorities, in a language that may indeed seem out-of-step with the times. In their language at least, if not the substance, they recall a movement belonging to a bygone age.

The 1890’s saw, in the rural America which is now thought of as the Republican heartland, one of the most sweeping and most radical movements in our history was taking place: the agrarian revolt which found expression in the People’s Party. This agrarian revolt, reacting to an inhumane crop-lien system which placed hundreds of thousands of farmers, white and black, into permanent and degrading economic dependence on ‘furnishing merchants’ (that is to say, loan sharks), issued a resounding call for: currency reform to broaden access to credit for the ‘industrial millions’; a graduated income tax; the establishment of a public postal savings banking system; and public ownership of – what else? – the railways, telecommunications infrastructure and postal system.

This agrarian movement, the Farmers’ Alliance, was based on both the idea and the practice of collective self-help: farmers involved in the revolt gradually found that they had to organise marketing cooperatives to get decent prices on their crops and fair terms on shipment and taxation, as well as consumer cooperatives to bargain collectively for the capital they needed to grow them. However, they soon found that merchants and financiers were conspiring to undermine their cooperative efforts, and that these efforts themselves were on shaky ground thanks to the hard-money currency system favoured by large banks. Under gold-standard induced currency contraction throughout the 1870’s and ‘80’s, farmers found their crops decreasing in value and their mortgages getting harder to bear under rising rates. The educational trial-and-error experiences of the farmers involved in these cooperatives convinced them that a wholesale overhaul of the nation’s financial system in favour of the indebted masses, and a nationalisation scheme to forestall speculation and abusive tolls on the new shipping infrastructure, were necessary to relieve the farmers’ debt burden.

But even at the time they were most active, they were derided and ignored as backwards, as economic illiterates, as people who wanted to ‘turn back the clock’ rather than progress boldly into the future. “Populists in their own time derived their most incisive power,” Duke historian Lawrence Goodwyn writes, “from the simple fact that they declined to participate in a central element of the emerging American faith. In an age of progress and forward motion, they had come to suspect that Horatio Alger was not real.” Tragically, the Populists were thwarted by the triangulations of their own elected officials. The gold standard was, for some while, retained. A system of popular credit which would distribute the ownership and productive power of the nation’s agriculture and industry into as many private hands as possible was never so much as considered. Instead, the Federal Reserve was created to shield from view the activities of the shakers and movers of the Gilded Age, the consolidating financiers. And the future into which a forward-looking, progressive, Republican-led nation boldly strode, beginning with the election of 1896, was one of penury, humiliation and crushing debt for millions of rural Southern farmers, spanning three full generations.

But still deeper among the tragedies of the Populists, according to Goodwyn, is that their defeat presaged a new society and a new set of cultural expectations which were entirely structured according to the interests of the financial elites. These corporate and financial elites did not, of course, object to ‘progressive’ reforms, as long as they were carefully stage-managed from within the political class they controlled, and as long as they were approached in timid, incremental terms which left these same elites unthreatened. But it was progress that came at a cost. In Goodwyn’s words, by the twentieth century, “a consensus thus came to be silently ratified: reform politics need not concern itself with structural alteration of the economic customs of the society. This conclusion… had the effect of removing from mainstream reform politics the idea of people in an industrial society gaining significant degrees of autonomy in the structure of their own lives.”

Even nowadays, as both the Sanders campaign in America and the Corbyn campaign in Britain show, challenging certain prevailing ‘economic customs’ of the neoliberal corporate society is a remarkably easy way of being branded as out-of-step with the times. It is worthwhile to note, though, that the candidates who are using populistic language and appealing to a populistic worldview in the United States, are not doing so in the organised way that the Alliance and Populist statesmen of 125 years ago did.

To be fair to him, Sanders (along with sympathetic libertarians like Ron Paul) has raised the issue of auditing the Federal Reserve in the past, and indeed has followed up on it some with, for example, the aforementioned proposal to break up the ‘too big to fail’ banks. And Corbyn is tapping into a common set of cultural complaints among particularly the disaffected youth of Britain. But proposals like theirs come from the top down and require a specialised knowledge of policy, the likes of which the original Farmers’ Alliance and the Populist movement inculcated in all of its members through the experience of the cooperatives. As Goodwyn points out quite astutely, such proposals cannot become the basis for a broad-based movement (and indeed, will often fall prey to other, divisive and sectarian, forms of symbolic politics along the way) unless they are accompanied by an equally broad-based collective experience of the logic of the credit market.

The sophisticated critiques of credit which they adapted from the Yankee greenbackers would in some important ways presage the slightly-later critiques of British thinkers like Gilbert Chesterton, Arthur Penty and especially Alfred Orage and Cecil Douglas – whose ideas, like those of the Alliancemen, were also adapted into various cooperative and social-credit movements in Britain and Canada. But the Alliancemen of Texas, Georgia, Kansas and Arkansas showed, perhaps, a distinctively North American faith in the democratic idea, and they followed it as far as it would lead. In their own day, that faith was downtrodden by the forces of progress – particularly as they coopted the democratic language and used it to justify a culture which severed the lives and livelihoods of the plain folk from the knowledge of the systems that governed them. But if Sanders and Corbyn are indeed facing backwards on a Populist-light platform, they would do well to take heed while they have full view: the history of the original Populists would seem to suggest that, for better or for worse, the question which governs their success or failure will in all likelihood lie in the educative potential of the grassroots.

(Image source)

Excellent piece, especially in its hint that some form of populism is groaning to be born. It’s that “educative potential of the grassroots” that is so dismaying to our hopes.

“Shortly afterward, Jeremy Corbyn – the left-leaning, anti-war MP currently running for the Labour leadership ”

I guess that’s FPR code for what people who use colloquial English would call a ‘Jew-hating labor meathead’.

Comments are closed.