Queens, NY

The city goes on. And this phenomenon, of a city continuing even as it is under threat or attacked– of resiliency in a city– is surely one of the great signs of its health. Victor Hugo describes this phenomenon with regard to the urban insurgencies of the 19th century:

“Paris accustoms itself very quickly to everything– it is only an uprising– and Paris is so busy that it does not trouble itself for so slight a thing. These colossal cities alone can contain at the same time a civil war, and an indescribably strange tranquility. Usually, when the insurrection begins…there is firing at the street-corners, in an arcade, in a cul-de-sac; barricades are taken, lost, and retaken; blood flows; the fronts of the houses are riddled with grapeshot; corpses encumber the pavements. A few streets off, you hear the clicking of billiard balls in the cafes. The theaters open their doors and play comedies; the curious chat and laugh two steps from these streets filled with war…At the time of the insurrection of the 12th of May, 1839, in the Rue Saint Martin, a little infirm old man, drawing a hand-cart surmounted by a tricolored rag…went back and forth from the barricade to the troops and the troops to the barricade, impartially offering glasses of cocoa– now to the government, now to the anarchy.”

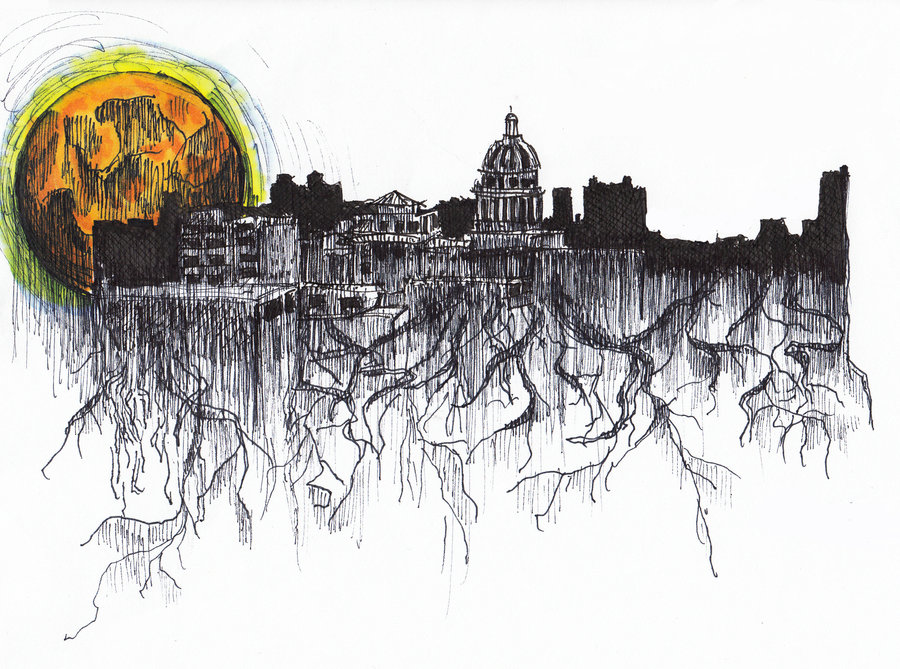

New York was, before September 11, perhaps the city that had most thoroughly apparently accepted the hypothesis of the End of History. Full of Last Men who chugged through their jobs at Andersen Consulting, believing the city where they lived city to be invulnerable and un-physical, they have been taught by the series of disasters we’ve endured– 9/11, the blackout, Sandy, various bombings– that theirs is instead a city in history, and that means that it is a city where anything might happen. It is a city where you cannot run your life by algorithms, but one where you have to continue to exercise the prudential judgement, the “practical reason” or everyday wisdom, that humans have had to exercise in every age. It is this activity, risky, un-mathematical, this phenomenon of “love choosing wisely,” as Augustine says, that most truly, under grace, shapes our souls, and cities-in-history are preeminently the places where such dramas take place. This is what New York has, since September 11, rediscovered itself to be: It is a city where you might at any moment be called on to take action– perhaps by yourself, but more likely, as a member of a crew.

The crews that did boat lifts off the sea wall in lower Manhattan on 9/11 rose to this call par excellence, and so did the homeless guys who found the third bomb, the day of the Chelsea bombing: they’d snatched the bag it was in, saw what they had on their hands, and called the cops. They were acting, in that moment, like one of these crews; an association for private good mobilized towards the good of the city.

So, what is the economic or political system that most effectively promotes the formation of these crews, and thus most effectively promotes the thriving of the civitas? It is possible for these crews to exist in city agencies; I have seen it. It’s possible for them to exist among the employees of large corporations.

But it’s difficult. The dynamics of state-owned enterprises and large corporations alike militate against crew formation. One is simply more likely to find a crew among the baristas at an independent coffeehouse than among the baristas at a Starbucks; the social reality of a work group, the experienced solidarity of shared work, which gives work so much of its delight, doesn’t always happen.

It doesn’t– but it should. And economic arrangements and political programs can either help or hinder the formation and cultivation of crews. Widely distributed small property, human-scale enterprises, are what make for a city of crews. And that is why I remain a partisan of private productive property.

The theopolitical blogosphere has recently been aflutter with a call for a renewed theologically conservative Catholic socialism. While that call was nuanced, presenting a version of socialism that preserves private personal property and even some private business ownership, the emphasis is wrong: crews, these work groups that I’ve been describing, belong properly and not just incidentally to the private sphere. Collegia and families are the stuff of which the civitas is made; they are not themselves properly public, though they are political. That is why the ideal must remain widely distributed private ownership of property, ownership by families, or ownership by the kind of corporation that is the legal structure within which such crews as I’ve been describing seem best to be embodied.

Thus with regard to the recent Tradinista Manifesto I remain a Contra. Though this is difficult, because the group which has put out the Manifesto is quite appealing, a true example, as are all revolutionary cadres, of just such a crew.

V: A Radical Christian Urbanism

As we now enter a world that is mostly urban, it is our urgent task to identify and cultivate sources of generative, welcoming and playful order in our cities so that, living in them well, we find that they in turn promote this order in ourselves and in our families. What this will take is nothing less than seeking a renewed understanding of and obedience to the natural law as it applies to city living.

In Frater Urban’s talk several weeks ago, he called for a radicalism that gets behind the stale oppositions between left and right. And he’s right to do so. He identified that radicalism with choosing a monastic life. But surely the true radicalism is the one that transcends the opposition between monastic and secular life. This true radicalism sees both Church and State, both cloister and campus, both country and city, as redeemable. I will not say “do not join a monastery;” what I’ll say is, “if you become a citizen of a city, you are doing something as strange and countercultural and illiberal and holy as joining a monastery, if you only knew it.”

We must give the city its due. That means regarding politics not as an illegitimate violence-based corruption of economics, but as something good and natural, though according, to be sure, to second nature; something the purpose of which is the worship of God, the virtue of citizens; and the support of their loving acts towards each other. And it means regarding cities as things which God sees and loves, and not as idolatrous mockeries of the church. Our citizenship is in heaven, to be sure. But it is also, for some of us, in New York, in Detroit, in South Bend. Christ is the King of the kings of the earth; he is also the rightful Lord of all Lord Mayors. This means that what we do in cities, how we love each other, how we live with our families, and yes, how we work with our crews, matter eternally. Modern cities are as embedded in history and in morally-weighted adventure as any medieval kingdom. And it may be that there are aspects of New York that will have their own apotheosis in the New Jerusalem.

This takes Jane Jacob’s insights to a new level – the Logos of a properly ordered civitas. Well done.

Comments are closed.