In his essay “Authority and American Usage,” David Foster Wallace defines a “SNOOT” as “a really extreme usage fanatic, the sort of person whose idea of Sunday fun is to hunt for mistakes” in a weekend column. He argues SNOOTitude runs in families, and SNOOTs generally find listening to most people’s public English “like watching somebody use a Stradivarius to pound nails. We are the Few, the Proud, the More or Less Constantly Appalled at Everyone Else.”

Though I and my family hardly hold a candle to Wallace’s SNOOTitude, I recognize some SNOOTish tendencies within my kin. My family table is the kind of place where using “beg the question” correctly would earn a hearty, genuine thanks. The correct pronunciation of “forte,” as in “That’s really not his forte,” is a matter of ongoing discussion. So we were all intrigued by Eli Burnstein’s new book, The Dictionary of Fine Distinctions.

Finally, I hoped, someone to clarify if you are “champing” or “chomping” at the bit, if you “home” or “hone” in, if it comes down the “pike” or the “pipe.” (For my money, it’s champ, home, and pike). Alas, despite the promising title, Burnstein’s book is no usage guide, no triumphant handbook for the SNOOT. Rather than offering entries that leave you saying, “aha!” and striding confidently to confront your misinformed brother, they’re more likely to leave you saying, “Oh. I suppose I’d never considered the difference between a mesa and a butte.”

That’s not to say the book is a drag or uninformative. I learned all sorts of things, like the difference between a joint, spliff, and a blunt (a joint is straight cannabis, a spliff sprinkles in tobacco, and a blunt wraps cannabis in tobacco paper). Although I admit, reviewing illustrations and text descriptions (multiple times) to differentiate between popular recreational drugs induces a sinking feeling that you are a complete square. Caveat lector.

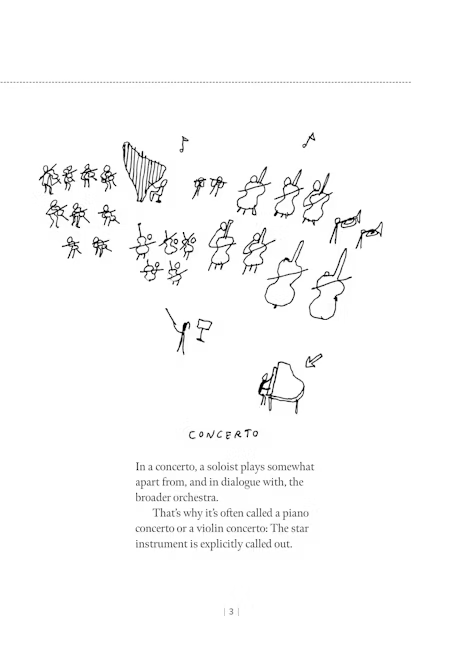

There are other good tidbits. Flotsam is “debris that spills out from a shipwreck of its own accord.” Jetsam is “debris that’s deliberately thrown overboard—namely, in order to prevent a shipwreck.” Flotsam and jetsam seems to always go together, though theoretically in a catastrophic, unexpected shipwreck, flotsam could float alone. Accompanying all these definitions are illustrations by Liana Finck that look straight out of the game Pictionary (in a good way).

They are hand drawn and immediately comprehensible and look like a slightly better version of how you yourself would sketch the difference between second cousins and cousins “once removed” (Burnstein clarifies that “Cousinhood is horizontal. Removalhood is vertical. If you don’t hear the word “removed” you’re in the same generation.” Your first cousin shares a grandparent with you, your second cousin shares a great-grandparent and so on. Your first cousin once removed is your first cousin’s child (or your parent’s first cousin). This is the place where Finck’s little sketches are very helpful).

Even though Burnstein, who calls himself a “humor writer” and not a grammarian, tries to keep things light, a few SNOOTy entries sneak in. Your friends may well appreciate your clarification that sorbet is nondairy while sherbet may add some egg, gelatin, or milkfat, but try correcting them on a misuse of hors d’oeuvre vs. canapé vs. crudité vs. amuse-bouche and see how far you get. Burnstein attempts to entertain, but the specter of the usage wars and authority is always lurking.

Burnstein’s target audience stands for norms, tradition, and linguistic conservatism. These are SNOOTs or SNOOT-adjacents, the kind of people who care to know whether sherbet and sherbert are both acceptable spellings (Answer: a contested yes). It doesn’t take much imagination to see how in a world where math is racist, entries on “Assume vs. Presume” or “Squash vs. Racquetball” present easy targets for motivated activists hoping to “decenter” WASP culture and dialect.

Normative judgments are uncool. And while Burnstein attempts to tap dance around them by focusing on clarifications rather than verdicts, this book wreaks of SNOOT. Yet it lacks that killer instinct, that thrill of battle. All Burnstein’s battles are won by forfeit. There are no entrenched camps in the “Lute vs. Lyre” or “Latte vs. Cortado” debate. By shying away from “fine distinctions” on matters of public disagreement, Burnstein alienates his core demographic: SNOOTs, those who relish being right.

Moreover, some entries feel simply out of place. The difference between stocks and bonds is more a matter of financial than grammatical interest, yet he includes not only these two but a further discussion of “equity” and “security.” He defines a conventional deadlift as extending all the way to the floor compared to a Romanian deadlift where “you don’t.” This definition is both incorrect and deeply offensive to Romanians everywhere.

In point of fact, Romanian deadlift is not a shorter range of motion but a different hinge pattern that targets your posterior chain, specifically your hamstrings. I repeat, if you do a deadlift without touching the floor, you are not “Romanian,” you are either rehabbing or you are a shrimp. No two ways about it, Eli.

In the end, Dictionary of Fine Distinctions is a bit bland: not controversial but not particularly entertaining; not a grammar book, but not really a humor book; neither fish nor fowl, likely to leave SNOOTs cold and normies bored. I suppose when it comes to discussions of the English language, I prefer sterner stuff.

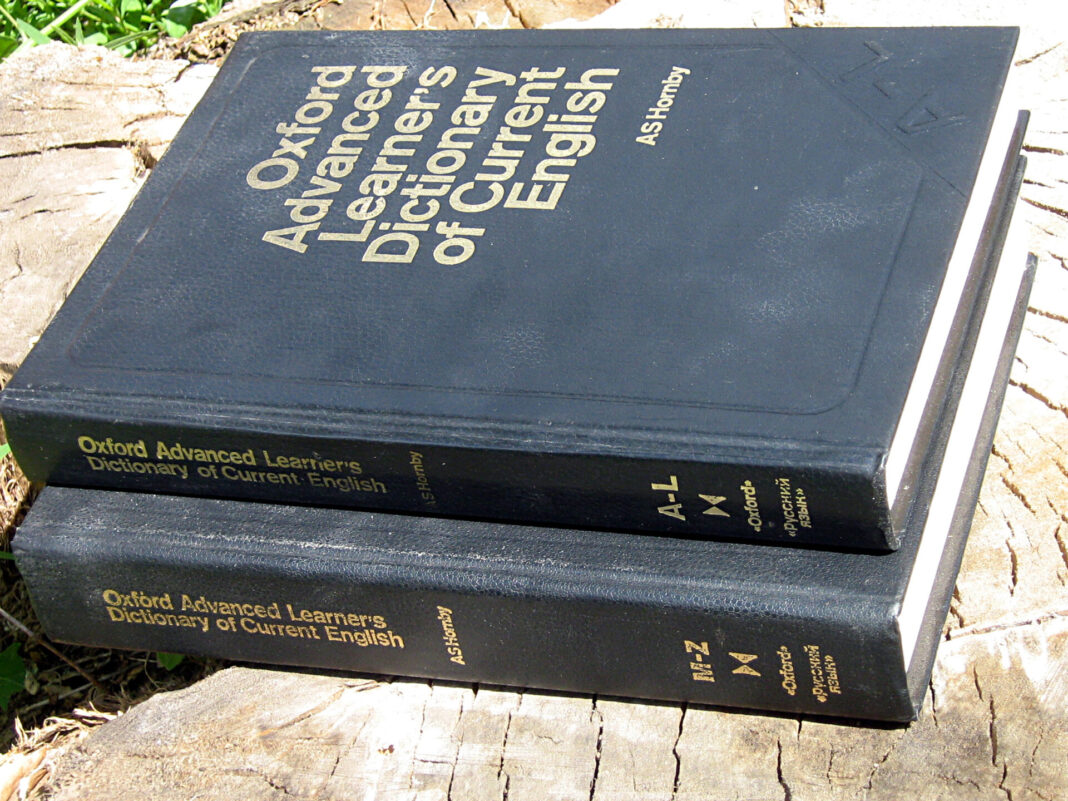

Image via Wikimedia Commons

If you confound wreaks with reeks, your SNOOT card is hereby revoked.

With good reason. “Pride goeth before destruction.”

As the editor of the piece, I hereby revoke my own SNOOT card for one day.

I was happy to see the book insist on what I see as the consequential distinction between jealousy and envy. I’ve earned the sense that either nobody sees the difference or nobody cares. For all the therapeutic blather circulating, so few actually want to understand what they are experiencing.