Devon, PA. Most people, agrarian or otherwise, do not read poetry anymore. Ours is not merely a forgetful culture, but one that has long since ceased to approve of memory as something more than a faculty. It used to be an art, however; and if a culture fails to appreciate or see practical necessity in the art of indelibly inscribing great rhetoric in the mind, or rather, in rhetoric whose greatness makes it memorable, that culture likely will not find much merit in poems either.

Poetic meter and rhyme had their origin as mnemonic devices, aiding the retention of vast strands of story, reflection, satire, and praise. As is true of any enduring reality, these things developed and grew more sophisticated over centuries, so that the mnemonic function became also a means to improvisation; if one of Homer’s heirs forgot a line, the metrical pattern helped him carry on speaking—“across the wine-dark sea”—until he found the thread.

In the age of manuscript culture and, much more so, print culture, these mnemonic and oral conveniences lost much of their importance, and the intricate stanzas most of us can identify as “poetry” on sight developed. Even so, without a love and use for the art of memory, one probably cannot long care for poetry. Too much of its interest is entangled with hearing it as something spoken and yet permanent; the only way human beings can possess such an eternal word is to chisel it onto the firmest stone of their memories. The Victorians, instructively, had a great taste for redundant ballads, because the refrains aided memorization and made recitation exciting even when the matter was trite.

The preceding comments I offer as a sort of apology. For, if few men think much on poetry, then even fewer preoccupy themselves with a particular poetic mystery. I have long been wondering how not just poems, but religious poems, get written. The great Christian poems of the Seventeenth-Century metaphysical poets, above all, seem sometimes almost inexplicable. As most people at least will remember from high school, these poets conceived their verses according to the extended trope, the conceit. John Donne’s “Batter My Heart,” for instance, creates a sonnet-length figurative comparison between the experience of sinfulness and conversion, and that of a town usurped by its enemy and under siege by its savior. One readily grasps the formal mechanics of such a poem, but not the foundation that makes it so striking. The poem seems to express some truth about the nature of Christian belief, about the reluctant and inconstant worship that constitutes the religion of a Personal God.

But much modern religious verse fails to be so expressive. Briefly, much of it stumbles into a crude piety that seems to speak from the heart—if it does indeed speak from there—of the pious soul some of us might like to have but seldom do. Contemporary religious poetry—such as that of Marjorie Maddox, whose work I reviewed in a recent Pleiades—takes a stab at filtering the old metaphysical conceit through modern surrealist juxtapositions, in hopes of startling us into a real encounter with the divine. Some of Maddox’s poems envision God dressed up as a clown on Halloween, or describe the Incarnation of Christ in terms of spirit pulling on a rubber surgical glove. I find something clever there, but nothing comparable to the method or intention of the metaphysicals.

If modern poetry cannot convincingly capture or express what it means to believe in God, one wonders if our age is any longer capable of such belief. Has religious belief been so emptied of experiential content that its inexpressibility as poem inversely suggests its life-in-death as a kind of system that counters experience, an imposition of the will against the memory and understanding,—as an ideology?

A possible place to begin contemplating such questions is George Herbert’s (1593-1633) little shrub of a verse, “Love-joy.” A brief didactic anecdote entirely unimpressive at first glance, it reads thus:

As on a window late I cast mine eye,

I saw a vine drop grapes with J and C

Anneal’d on every bunch. One standing by

Ask’d what it meant. I (who am never loth

To spend my judgement) said, It seem’d to me

To be the body and the letters both

Of Joy and Charity. Sir, you have not miss’d,

The man reply’d. It figures JESUS CHRIST.

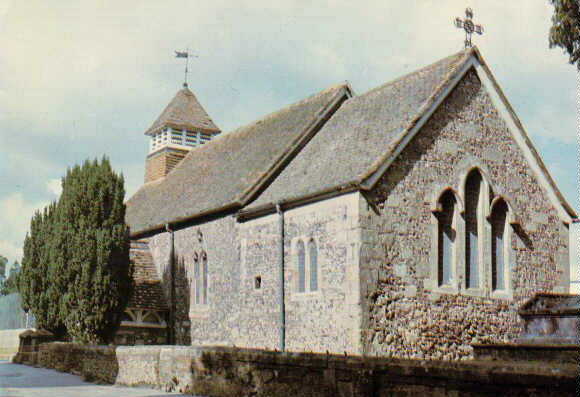

The poet, who spent the last years of his life as a parson at St. Andrews Church in Bemerton, relates this exchange. He sees before his eyes two letters printed on a bunch of grapes; the “As” sounds for a moment as if a simile is about to occur, but we quickly realize he means simply, “As I was looking at a stained glass window, I noticed these lettered grapes.” Some fellow nearby asks him to explain what those letters stand for, and the prim parson who loves to share his opinions explains that the letters stand for “Joy” and “Charity.” The interlocutor says, “Yes, you’re right”—even though literally the parson errs. But, figuratively, the parson speaks the truth, for Joy and Charity are attributes of Jesus Christ.

So many of the familiar metaphysical poems—Herbert’s “The Collar,” and “The Pulley,” or Donne’s “Valediction” and “Flea”—seek, it seems, to startle us with the unanticipated and counter-intuitive tropes on which they are built. This one gives us an account of how organic or natural the conception of such tropes actually can be: the counter-intuitive trope reveals an intuitive quotidian reality. Herbert lived in a Christian landscape. Passing along the side of St. Andrews, perhaps on his way to pay a visit or head home for dinner, he would see the diverse “annealing” acts that human beings had gone about to inscribe the surface of their lives with reminders of its Creator.

His poems of devotion arose naturally from a life saturated by, and in contemplation of, the adjuncts and equipment of mundane Christian habit. What he normally sees reveals what he cannot see; what appears to be a mistake, or failure to see the truth, opens onto the True itself; and the written letters of the things of this world speak almost incidentally of the Divine Body. But one must live with a certain literal constancy, cultivating and contemplating a steady place, if one hopes to see through its surfaces to the heights and depths they can only intimate.

This poem might have been written otherwise, concealing the quotidian origin of grapes annealed with J and C, and leaving only the trope. But here, in a particularly candid tableau, Herbert suggests to us that to speak of the divine—in poetry or anywhere—requires spending one’s life among often unremarkable reminders, the minor features of human life that only occasionally stir the mind to recall the source of itself.

The tendency to secularize the places in which we dwell finds its violent origins in the iconoclasm of early Protestant sects, and Herbert was not without his iconoclastic side. We live in a world largely wiped clean by that secularizing impulse—so much so that the impulse itself has become secular. This has wrought for us a world that seems determined to the profane—in the ecclesiastic sense of that word. The devotion one finds in this Herbert poem thus suggests that the interest and achievement of the religious verse of his age results not precisely from a more sophisticated and sincere piety, but from a people who recognized piety and reflection as a good and so worked to shape the material world—in “body and the letters both”—that it might lead them to meditate on the divine one. Paradoxically, two letters here embody the incarnate God, and so preach his “letter,” the good news (joy) of charity. In the process of this shaping, the material reveals itself as a gift of the divine and as a mute expression of its truth.

. . . . “to speak of the divine—in poetry or anywhere—requires spending one’s life among often unremarkable reminders, the minor features of human life that only occasionally stir the mind to recall the source of itself.”

My friend Robinstarfish recalls with joyful, light-filled simplicity the source of himself in almost everyone of his daily photo haikus. You may visit them here.

Thanks for your lovely post. I found your site through the website “Anglican Curmudgeon”. I also apprecaite the beautiful pictures of the church. George Herbert is one of my favorite poets as are John Donne and Gerard Manley Hopkins. One of the moderns poets I like who wrote about faith was Jane Kenyon.

Best to you.

Not incidentally, the pictures are interior and exterior views of Herbert’s parish church. I couldn’t find any annealed grapes, but I’m still looking.

In her _Culture and the Thomist Tradition_ Tracey Rowland argues that modernity is a culture of forced forgetting (77) in distinction to Christian understandings of a life of “celebrated recurrence.” Certainly Augustine, Aquinas, Bonaventure have much to say about the role of memory in wisdom and/or prudence.

In some wonderful discussions, she argues that memory is related to the theological virtue of hope and the transcendental property of beauty, and that the forced forgetfullness of mass culture goes far in explaining our culture of death and the loss of beauty. Poetry would be both means and ends of a cure, thus.

A side note: there is an interesting historical question then. Rowland writes this text as part of the Radical Orthodoxy series. RO very often blames late medieval philosophy/theology as causing the secular. So rather than finding that “[t]he tendency to secularize the places in which we dwell finds its violent origins in the iconoclasm of early Protestant sects,” as does the post above, this school of thought points to Scotus and Ockham as originating the iconclasm (which they do by insisting of the univocity rather than the analogy of being–aside, I’m trying to figure out how to save the Scotistic Manley Hopkins from this charge.)If RO is at all correct, then the violent rejection of place is a theological problem: insofar as things are just things, ie, insofar as things do not receive or participate their being in some analogous relationship to God, things sink into the nihil. No longer guaranteed dignity by their very contingency–God need not have created them, but he does, thus they have enormous worth–the particular material instances no longer matter. They just happen to be, and one can always look for a better place, ie, one that satisfies arbitrary desires more. The particular place matters only in relationship to God; absent that relationship it doesn’t matter; given that relationship it matters!

And there are some good reasons to think that the beautiful (known by Augustinian memory, perhaps by poetry)and its concomitant hope thus give meaning to particular place.

So much to think through in response to your post. Thanks for a good occasion to do so.

Dr. Snell has firmly established himself, during the short life of FPR, as worthy not only of “commenter” but contributor status, and my post is dilated and deepened by his reflections.

Because reason, for Aquinas, is never the individual’s carte blanche reason, but that of an entire tradition of thought, memory is not simply a “contributor” to the reasoning mind, but is effectively one with it. I’ll address this in a future post on reason and modernity, but would just say here the same thing I say to my students when teaching them Confessions Book X, “Memory is simply the whole contents of the mind.” It is what the mind reasons or understands when it tries to understand.

I am far from feeling I have grappled with the insights and implications of Radical Orthodoxy. But I can at least suggest that Gerard Manley Hopkins’ use of Scotus ought not compromise his work, even should we rule late Franciscan metaphysics suspect. Hopkins reads Scotus largely through, or alongside, Newman; his celebration of haecceity — the irreducible individuality of each being, each real thing — is secondary to his doctrine of “inscape,” which I would define, briefly, as the inherent polysemantic nature of all things. Things bear their meaning within them in an ontological manner — not simply their individual identities, but their memberships in species (and perhaps genus?), and also the various significations that we associate with “meaning.”

Hopkins’ inscape, so often misunderstood, opperates in part according to a set of moderate realist metaphysical propositions. If Scotus can been deemed a nominalist — and this is still a live question among medievalists, as I understand it — his nominalism is transformed by Hopkins into a pure incarnationalism, and surely the Incarnation is not in tension with the Thomist and (above all) the earlier Augustinian realism that Radical Orthodoxy endorses. Waterman-Ward’s book on Hopkins is splendid in sorting out these problems.

My last paragraph introduces the historical problem of when the “secularization” begins. From a certain perspective, it has long been argued that Christianity itself intiates the “disenchantment” of the world. This is obviously false as a historical matter, but has been made a real question when certain, I presume Barthian, thinkers on the Christian Revelation try to lay claim to that Revelation’s history. Louis Dupre’s “Passage to Modernity” provides an account of secularization as a product of the early modern division of nature and grace; his account has always been the most convincing to me.

You might see my “St. Augustine and the Meaning of Art,” if you are interested in more informal reflection on this particular subject.

The previous response has helped me very much, and I am grateful.

The RO argument, alas, on occasion sounds like 1. Scotus bad, 2. thinker x is a Scotist, 3. Thinker x is bad. I hope I didn’t make that error. But I must admit that I do worry about the implications of haecceity, or at least how that position could develop into a philosophical anthropology and politics I find troubling. The notion of Hopkins’ inscape as primary and incarnational was delightful. Thanks for that very helpful corrective and augmentation.

Could you say more on the meaning of “polysemantic nature”? As I take your explanation, inscape reveals not just the isolated individual form but also the nexus of relationships which makes the form itself? (Assuming that to have form is to have form in relation.) Could one then read Hopkins as something of a personalist in a broad family resemblance to Maritain or Norris Clarke? That would be delightful.

Secularization: I’m with you on this. Whatever the particular thinker or moment, a mistaken nature/grace distinction must be part of the narrative of secularization. Things are never just themselves but always more, they bear weight and do not sink into unbearable lightness. Things have iconic depth (Christ plays!)because nature is itself as a gift and has a supernatural vocation as telos. The natural end is supernatural. And Dupre nails that. I wonder what you would think is the proper place of de Lubac and thinkers like David Schindler in a defense of place/limits/liberty.

Thanks for an intelligent, nuanced post and response. Would enjoy reading more from you on poetry.

I read Hopkins’s notion of inscape as arguing almost precisely what Maritain argues (following John of St. Thomas) on signs. Some relations are mere relations of the mind (second intentions), but many relations between beings are themselves ontological, which is what Maritain signals by intentional being. As Maritain would elaborate, of course, since the mind is ordered to being, there is nothing that we know that does not have some ontic reality, but I won’t press this point any further here. Pressing such a point, however, is the argument of the book I’m drumming up on T.S. Eliot and Maritain. I believe you have understood my argument about things being ontologically polysemantically perfectly.

A few quick replies: To my shame, I know Norris Clarke’s work only at second hand. Schindler(s) (it perhaps goes almost without saying) and de Lubac have immense contributions to make in this conversation. Your introducing their names has inspired me to plan a post on the relation of Lubac’s ecclesiology as a response to modern deracination. Let me leave off with that promise — or threat.

A thought on Franciscan thought: Francis was a poet and mystic, whose appreciation of the intense individuality of each created being is the heart of a healthy spirituality of creation. Part of that sensibility is also recognizing the intense relation of dependency on the Creator. (Chesterton describes this marvelously in his biography of Francis.) If you try to capture this in non-poetic philosophy, you run a serious risk of one-sidedly emphasizing the irreducible individuality (nominalism) or the total relationality all the way down (flirting with gnosticism). I think either way you end up throwing the nature-grace relationship out of whack.

What a rich and beautifully written post – the Curmudgeon was right in recommending this post and site.

Thank you for reminding us of the beauty and power of poetry and of years in school memorizing poetry and Shakespeare. Nowadays putting Scripture into my mind is my need and nourishment.

Do you also see Jesus in Herbert’s poem as the ‘One standing by’ (Hebrews 13:5) who ‘Ask’d what it meant’ (Jesus always asks tough piercing questions with unerring purposes and aims, Socratic questions) and Who is ‘The man’ (John 19:6)… JESUS CHRIST?

Donne’s The Cross is a favorite of mine…and His Lenten Hymn, ‘Wilt Thou Forgive’.

Blessings,

Georgia in Tallahassee, FL

Dear Georgia,

Certainly one could find in this short poem some echo of the journey to Emmaus, or indeed to any of the post-Resurrection moments where the Apostles and disciples fail to recognize Jesus on sight and are brought into recognition of him only through some soft-push of an interogative.

I would even suggest that this is a necessary component in any reading of the poem, and must surely have been wrapped up in Herbert’s intentions. We have good basis for this in Herbert’s other poems; many of them seek to narrate how the soul comes to God’s grace only to discover that it had the intimations of that grace already. So, in this poem, Christ might already be present not only in the letters but in the flesh (by apparition) as the unknown and unanticipated stranger standing by and prompting the poet to reflection. There is much to contemplate here that deepens my understanding of the poem.

What prompted me to write on this poem was the way in which its fantastic trope arises from mundane or quotidian experience. As such, I may have blinded myself to the possibility of reading the presence of the man as itself something super-mundane, i.e. miraculous. But I am so glad you wrote, for I see that such a reading is not only supportable but perhaps formative to the poem.

It might be worth contemplating to what extent substituting Scripture for poetry and other things enacts the process of “secularization” described in the last paragraph. If one cannot find Christ playing in a thousand places, perhaps the Incarnation hasn’t been made real enough. Certainly that was Herbert’s concern as a parson, when he saw his parishioners losing all sense of the sacred in their ordinary life. On this, see his short book “The Country Parson,” which is dry but fascinating.

Dear Mr. Wilson,

Scripture IS poetry. Nature is both poetry and Scripture’s witness.

Scripture and nature together testify to the goodness, beauty, character in the will, intent, purpose and heart of The Poet and Artist who made them.

It is impossible, futile and actually destructive to silence or deny (secularize) nature’s revelation for long. The human soul hungers for God and yearns for Home. Secularization is an attempt to assuage or distract with another remedy, to secure to another mooring, like putting diesel in a gas engine…tethering a horse to a feather, one will ever fill or hold us steady as only God can.

MHO,

Georgia

Dear Georgia,

I certainly agree with your comments — or the heart of them at any rate.

The substance of last sentences of my previous comment was to indicate that a misapprehension of the nature of grace can lead to a contempt for creation or nature. In a strictly classical sense all things are poetry — they are made by the hands of God. That said, as you would no doubt agree, there is something singular about Scripture. It is “singular” in the sense that we cannot define it as belonging to some genus or genre. Scripture qua scripture isn’t “poetry” as that term is usually understood, though it contains poetry. Scripture is simply scripture: the revealed Word of God inscribed by human hands with the help of divine inspiration.

If Scripture is singular, and if our hearts have, by their nature, a telos, a destiny for life with God, and if grace is the sole means by which can fulfill that telos, then one may be tempted to dismiss the things of this world as irrelevent or even obstacles to our salvation. More often, some Protestant Christians have historically dismissed all the world, save the singular reality of Scripture, as if it were the unfortunate and contemptible reality the graced heart must struggled to overcome. As such, it becomes very tempting for such Christians to “secularize” the world, to condemn everything but the interior assent of faith a matter of indifference or an object of idolatry.

Herbert’s writings indicate he was aware of this temptation, and felt it had robbed his age of some of its piety, substance, and goodness. Confronted by our heavenly destinies, some Christians become “prematurely ecstatic” and attempt to depart from the body of this world as if it were in itself alien to Christ’s spirit. Such persons “secularize” the world, they deny its Christological origins and its Christological dependence, and they clear a space for that more advanced form of secularization — that which seeks to wipe the heart clean of its supernatural destiny for life in God.

Dr. Wilson,

I am so grateful for your wise and articulate writing, particularly your comments as they deepen my understanding of my morning study:

>>

He has made us competent as ministers of a new covenant–

not of the letter but of the Spirit; for the letter kills, but

the Spirit gives life. ~ 2 Corinthians 3:6 (NIV)

God has not cared that we should anywhere have assurance

of His very words; and that not merely, perhaps, because of

the tendency in His children to word-worship, false logic, and

corruption of the truth, but because He would not have them

oppressed by words, seeing that words, being human, and

therefore but partially capable, could not absolutely contain

or express what the Lord meant, and that even He must depend

for being understood upon the spirit of His disciple. Seeing

that it could not give life, the letter should not be throned

with power to kill.

George MacDonald (1824-1905), “The Knowing of the Son” Unspoken Sermons

<<

You might find this introduction to “An Interpreter of Life” by Lyman Abbott, a 1904 collection called The World’s Best Poetry, Volume III, ennobling.

Mark, et al,

Another Franciscan note: There might be better and worse ways to reflect philosophically upon Francis. In short, I think (some won’t be surprised to hear me say it) Bonaventure gets the balance right, and Scotus doesn’t. The difference for me is that Bonaventure’s a better Christian neoplatonist. I.e., the Neoplatonic tradition, especially in its Christian form, develops (I’m oversimplifying, I know) as a way of navigating the relationship between particulars and universals, between immanence and transcendence. What Francis expresses in the flexibility of the “per” in the Canticle of the Creatures (Praised be you, O Lord through/by my Brother Sun) is caught by Bonaventure in the sense that God is found in creation IN and THROUGH its signs (See Mind’s Journey into God I)

So I wouldn’t parse it as “poetry vs. philosophy,” but as better or worse philosophical frameworks.

In this, I think Hopkins still shows his Platonic colors, whether he knew it or not…And that brings together Norris Clark and Hopkins, together again for the very first time…

Thanks, Kevin. I know there’s a tendency that extends even back to Gilson and Maritain of “poeticizing” the Franciscans so that we don’t have to contend with their theology qua theology, or, rather, qua systematic theology. To set up a dualism between the poetic and the philosophical is — no offense to Mark! — a rank form of Kantianism. It quarantines the purpose of poetry to a so-called “purposive purposelessness,” as another Kevin (Hart) recently argued.

To repeat a note I struck above: it doesn’t strike me, based upon current scholarship, that defending Scotus is necessary to a sympathetic understanding of Hopkins. The Scotus he read was probably not the Scotus scholars now read, and functioned primarily to bring metaphysics firmly back into the center of a theology whose framework would otherwise have been basically idealist, i.e. derived from Newman’s “Grammar of Assent.” “Inscape,” according to Hopkins, is a blanket term for the polysemous meaning — the peels or layers of signification — found in any given thing. It is only in the idea of “Haecceity” that Scotus in his own singularity becomes important to interpreting Hopkins, but even here I would suggest Hopkins is more concerned with striking a note against the idealist tendencies to generalize in Victorian culture more than to tow the Franciscan line in any responsible way.

JMW, you wrote:

“Confronted by our heavenly destinies, some Christians become “prematurely ecstatic” and attempt to depart from the body of this world as if it were in itself alien to Christ’s spirit. Such persons “secularize” the world, they deny its Christological origins and its Christological dependence, and they clear a space for that more advanced form of secularization — that which seeks to wipe the heart clean of its supernatural destiny for life in God.”

Though you may never return to this post, see this or reply, I’d like to ask if you are referring to the Manicheans as rejecting the body and material world?

Do you mean by ‘secularizing the world’ the denial of the Creation by God and the advancing beyond that to denial of the necessity of bowing to the dominion, design and natural order of God? Is that what you mean by ‘wiping our heart clean of its destiny for life in God’?

Dear Georgia,

I had a rather extensive reply to your query prepared, but it occurs to me that you might simply have a look at Mark Shiffman’s essays on this site, which will certainly answer many of your questions. If they don’t, I’d be happy to take those questions up directly.

Thank you very much; I will look up those essays.

Mr. Wilson,

Thank you for this article. I have not read poetry for many years.

Mr. Herbert’s poem is lovely. I will try to find a book of his poems.

What a beautiful church!

Re-reading the poem again today, I was struck by the line, ‘To be the body and the letters both.’

The body and letters stand for ‘both’ the bodily Incarnate Christ and the Church, whom He seeks to make one with Him. The letters are His Word, the Bible and they are also ‘both’ one.

I hope you and your family are well and very blessed.

The letters are His Word, the Bible and they are also ‘both’ one – that is, Christ and The Word/Scripture are one in Spirit, in perfect accord.

Comments are closed.