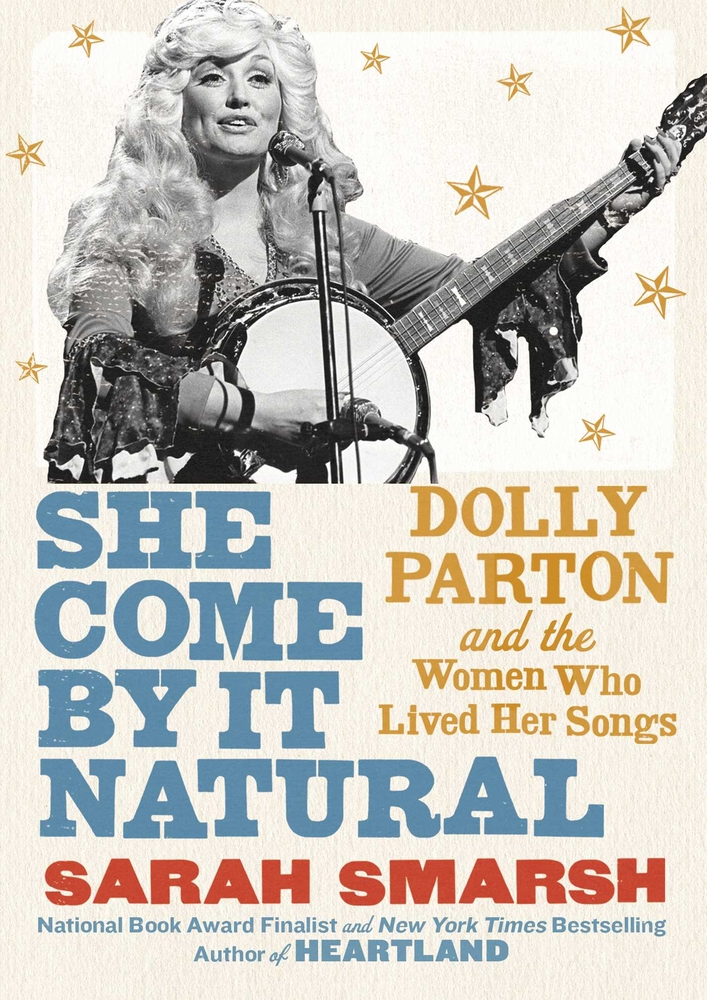

West Palm Beach, FL. She Come By It Natural: Dolly Parton and the Women Who Lived Her Songs is the newest book by Sarah Smarsh. Smarsh is best known for her 2018 work, Heartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on Earth, which was a finalist for the National Book Award. A Kansan by birth and by choice, Smarsh is one of many contemporary authors focusing attention on rural places and the life of working-class Americans. Smarsh’s insights are informed not only by academic study but by the experiences of her own family and the particularly rich example of her Grandma Betty. She Come By It Natural was written in the same period as Heartland, but it’s an exploration of the lives of rural, working-class women through the lens of Dolly Parton’s life and music.

Everyone seems to love Dolly Parton right now. While she has always had faithful fans, in the last few years she has become increasingly iconic for broader swathes of the American public. Part of her appeal is her ability to transcend partisan divisions, which was at the heart of Jad Abumrad’s 2019 podcast series Dolly Parton’s America. That same year Netflix released Heartstrings, a series which Parton produced, with stories based on her music. This year she has a new Christmas movie on the same platform. Her ongoing and increasing fame is all the more surprising considering that her songs, new and old, almost never play on country radio stations. People still love her music, but they are also drawn to her as a person. In 2020, she made Stephen Colbert cry with an old ballad, and she also made news when she donated a million dollars for COVID-19 research.

Smarsh begins She Come By It Natural by acknowledging Dolly Parton’s role in society today and her ability to unify disparate groups, but this book focuses on Dolly Parton as representative of working-class women. Parton was born in rural Tennessee to hard-working but poor parents who paid the doctor who delivered her with a sack of grain. She grew up playing music and performing, going on to Nashville where she became Porter Wagoner’s “girl singer” on TV. The show and duet albums brought her fame, but she was stifled by Wagoner’s desire to control her career. She left him, writing “I Will Always Love You” to break the news (there’s a good episode of “Drunk History” about this). Wagoner tried to break Parton for leaving him, but she triumphed, going on to astronomical solo success, movies, and musicals. Though her career has waxed and waned, she has shown herself to be a musical and business genius, who has built a legacy for her extended family and her region. Smarsh weaves this story into her narrative, using Parton’s autobiography, Dolly: My Life and Other Unfinished Business, as a touchstone and going beyond it, incorporating music lyrics, interviews, and more.

Many stories about people from rural places are ultimately stories about men. Smarsh uses this book to explore Dolly Parton and her music as reflective of rural, working-class women. Parton’s own life mirrors what others have experienced. She started off poor, performing on television before her family could afford to buy one. In Nashville she was subject to the sexism of the music industry and Porter Wagoner’s controlling influence. She had to defend herself and define her own course, which she did, surprising many men and women who wrongly associated her with the title of one of her early hits, “dumb blonde.” In She Come By It Natural, Smarsh draws parallels between Parton and women like her own grandmother, who also came from underprivileged backgrounds, worked hard jobs with little protection from male bosses, and came across few easy opportunities. Smarsh’s Grandma Betty wasn’t born into the high life, she had a child at seventeen and a string of bad relationships, but she made a life for herself nonetheless. She wasn’t afraid to walk away when she needed to and she listened to a lot of country music along the way.

For Smarsh, Parton didn’t just provide great music for the lives of working-class women, she was and is a great feminist role model. While Loretta Lynn has long been discussed in connection with the changing role of women, for songs like “The Pill” and “Don’t Come Home A-Drinkin’,” Parton has often been excluded from that kind of consideration, in part because of her appearance. People have mocked Parton’s exaggerated figure and tight clothes, but Smarsh shows us that those people have missed the meaning in these things. Parton has always described her look as modeled off the “town tramp” where she grew up, an image of beauty that stood apart from her life on the farm. Smarsh quotes Parton describing a similar fascination with pictures of models in newspapers, who “didn’t look at all like they had to work in the fields. They didn’t look like they had to take a spit bath in a dishpan.” Parton’s style reflects the desire of working-class women to claim femininity and define their own womanhood, something Smarsh herself saw growing up in rural Kansas. This aspiration is a part of the rural and working experience that we rarely read about.

What’s remarkable about Parton is not that she thought the town tramp was beautiful when she was a child, but that she still does. Parton never “classed up” her look or her language. She has shown women that you can get somewhere just the way you are. This is part of what makes Smarsh consider Parton something of a feminist icon, even if Parton herself doesn’t use the term. From her own educational background, Smarsh knows all about the world of “politicized terminology, which is usually the province of college-educated people,” but she also knows that while poor women “often resist” those terms and don’t “talk the talk,” they do walk the walk. “Working-class women might not be fighting for a cause with words, time, and money they don’t have, but they possess an unsurpassed wisdom about the way gender works in the world.” Smarsh doesn’t want us to just marvel at Dolly Parton’s ability to bring dignity to working-class women; Smarsh wants us to join Parton in recognizing the dignity of rural and working people and the value in their approach to life.

One theme in this book which seems present in almost all conversations about rural places in America is the question of leaving. So many rags to riches stories for country people seem to depend on a departure. Wendell Berry is exceptional, in part, for his commitment to Kentucky. The need to leave home is at the heart of Dolly Parton’s song “Wildflowers.” In the song she compares herself to a wildflower “needing freedom to grow.” She “grew up fast and wild” but different from others.

And the flowers I knew in the fields where I grew

Were content to be lost in the crowd

They were common and close, I had no room for growth

And I wanted so much to branch out

So I uprooted myself from my home ground and left

Took my dreams and I took to the road

And it turned out well for the “wild rambling rose, seeking mysteries untold” because

When a flower grows wild, it can always survive

Wildflowers don’t care where they grow

Dolly Parton did leave home. She had to. Her family loved her but didn’t approve of her clothes, her classmates didn’t believe in her vision, and there was no opportunity to become a famous singer without getting out. And eventually she left Nashville for Los Angeles, pop music, and the national scene. Today her brand has even “gone global.” You can see 9 to 5 on stage in London, and you can hear Dolly Parton on the radio in Africa. None of that would have happened if she hadn’t come down from the Smoky Mountains.

For Smarsh, “leaving” is especially tied to class and gender. It is often the only option for a poor woman. A middle-class woman might “lean in” to a situation that is less than optimal, as recommended by Sheryl Sandberg. She might “fight for parity with men in her corporate office and insist that her husband change diapers” and do much more in the community and the country. The middle-class woman has a foothold, a position to advocate for change from within the system. But “for the poor woman, there is much less social, economic, or cultural capital for changing a situation from the inside. But she might have a car and a bit of money for gas, which is enough to leave a situation behind.” Smarsh’s Grandma Betty left some abusive marriages in just this way. And Smarsh finds a special resonance with this experience in country music, writing that “there is something particularly poor, female, and American about leaving that happens in country music.” No wonder “I wanna be free” was one of Loretta Lynn’s hits.

Leaving is often the best option for disadvantaged or discouraged men across American country and roots music too. In “Blue Yodel #1” Jimmie Rodgers sang that he’d rather “drink muddy water and sleep in a holler log, than to stay Atlanta, treated like a dirty dog.” The situation could be a hostile city, or it could be an unhappy home. In “Leaving Blues” Leadbelly sang that he was “leaving, leaving my home, but I don’t know which way to go.” In that song, the woman he’d been living with for twenty years said “she don’t want me no more.” Of course, in the first half of the twentieth century many Americans did leave rural homes, riding the rails and driving west and looking for opportunity, hoping not to get arrested for vagrancy along the way. Woody Guthrie sang “I ain’t got no home, I’m just ‘a-roaming round, just a wandering worker, I go from town to town. The police make it hard wherever I may go and I ain’t got no home in this world anymore.” Leaving was not just commemorated in song; it was lived by huge portions of Americans, including the millions who participated in the Great Migration of African Americans out of a hostile rural South and into the urban North, looking for new opportunities.

It seems one of the central ways that rural places appear in country music is as places left behind. And yet. Dolly Parton as wildflower left the Smoky Mountains, but one of her most enduring songs is “Tennessee Mountain Home,” which celebrates her birthplace where “life is as peaceful as a baby’s sigh.” She moved away in her youth, but today Parton owns multiple homes in Tennessee. Through Dollywood, she has also helped to expand the economy of the region where she was born. She has even become something of a patron saint there, for her consistent charitable giving. Not only does her Imagination Library send books to kids, she was one of the first financial responders after the Smoky Mountain wildfires, because, she said, “I’m a Smoky Mountain girl. I mean, this is home. Charity begins at home, right?” If Dolly Parton left the Smoky Mountains, it seems to have been on a hero’s journey that Joseph Campbell would have recognized. She came back, bearing gifts.

This question of loving and leaving or leaving and loving seems central to the work of Sarah Smarsh, as well. In the foreword to She Come By It Natural, she writes that this story is also “about leaving home but never really leaving home.” Smarsh herself left Kansas for other opportunities but, unlike so many, she returned. She is even the host and executive producer of a podcast called The Homecomers, which focuses on “‘homecomers’ fighting for areas where the common narrative of American success would have them ‘get out.’” Some conservatives may not care for all of Smarsh’s politics, but her advocacy for the people who live in rural places and work late-night shifts should not be divisive for anyone who cares about the parts of the country that only get mentioned when the electoral college is being debated.

In “Coat of Many Colors,” Dolly Parton opens the song about her materially-poor but love-rich childhood singing “Back through the years I go wandering once again / Back to the seasons of my youth.” When America looks at rural places, it often has a sense of “looking back.” Country hometowns are meant to be left behind, like Altamont, Catawba in Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel. This mentality often applies to people from places with low population density and to the country as a whole. As the United States has in many ways left the rural life behind as a thing of the past, it has forgotten the rural people of the present. In You Can’t Go Home Again, Wolfe asserted that return was impossible. In her example, Dolly Parton shows an alternative. She has kept her twang and her ties to the Smoky Mountains. By keeping the look she loved as a child in Sevierville, she has also brought many working-class women up with her as she rose in the world. In She Come By It Natural, Smarsh urges us to keep listening to and loving not just Dolly Parton, but the lives of all working-class rural women.

Thank you. I will look for this book.

Dolly, the “dumb blonde,” is easily the most intelligent and articulate woman in the music business. It always seemed to me that she took her life seriously, but never herself seriously. She always knew where she was going, but never forgot where she came from.

Comments are closed.