Local Culture: A Journal of the Front Porch Republic is now in existence. To read it, you’ll have to subscribe. But you can peruse the contents of our first issue and read the editor’s opening letter, a manifesto of sorts for tangible goods, real places, and wry humor. You can also support our efforts to produce a quality journal by donating.

In March of 2009 a group of writers unenthusiastic about the dull similitude of the major political parties, unreconciled to the deadening monoculture around them, and wary of the power and money being sucked toward a center that cannot hold, discovered amid their several disaffections that they shared certain commitments, among them a devotion to place, a respect for limits, and a nostalgia for liberty (also the capacity to use “nostalgia” without the usual progressivist sneer). So they did the most sensible thing they could think of: they shackled themselves to a borderless noplace by launching a website. They called it Front Porch Republic and adopted the tag “Place. Limits. Liberty.”

The governing idea was not complicated: to write about human flourishing—what it looks like, what we need if we’re to achieve it, what its scale might be, and what stands in its way, including (among other things) the dull political parties, the deadening monoculture, and centralization. The project was to be at once serious and light-hearted, solemn and jocular, as befits creatures “darkly wise and rudely great / . . . in endless error hurled; / The glory, jest, and riddle of the world.” They were prepared to endure a little scorn, and did, for a website is manifestly not a place. It is an antiplace. It is a “site” only in quotation marks, and you go to it only by “going” to it, which means going nowhere but to your chair to sit in front of a screen, cut off from other people, declining life’s daily offer to inhabit the fullness of the human condition—the bodily, placed, social, upright, snow-shoveling and football-tossing incarnate human condition.

The joke was not lost on them. They knew they were supping with the devil; they knew to take up long spoons. To fend off the charge of hypocrisy they put on the armor of irony.

But still they were writing for a website. What would Chesterton think?

It would have been theologically naïve of these writers to think that nothing good could come of their efforts, whether ironic or hypocritical. Lust may be perjured and murderous, as the bard said, but from it image-bearing children sometimes spring forth. (Front Porchers aren’t jet-setting careerists; they like children.) But one goal of FPR was to defend and preserve the printed page and to do so by establishing a press. Two early triumphs in that effort were David Bosworth’s The Demise of Virtue in Virtual America (2014) and Bill Kauffman’s Poetry Night at the Ball Park (2015), the first titles to issue from Front Porch Republic books, an imprint of Wipf & Stock Publishers. Several books with real pages that you can turn and dog-ear followed, and more are forthcoming, each in keeping with the initial disaffections and the initial commitments of 2009—both sorely needed after the banking swindle and financial carnage of 2008.

But there remained the goal of bringing out a print journal, and doing so before the inaugural project, such as it was, ran out of steam. For the Front Porchers hadn’t just fallen off the turnip wagon, as some of their critics insisted. They knew that “things” in the pixelated “world” come and go pretty quickly and that “sites” can vanish into the ethereal tartarus they came from.

But to their surprise the project has endured into its second decade. It turns out that they—that we—are not alone. There are others out there who are wary of centralization, unenthusiastic about dull similitudes, and unreconciled to monocultures, whether in the form of the immersive witlessness achieved by television and mass media or the amber waves of glyphosate imposed by official U.S. farm policy—a policy the warring parties, that for all their distinctiveness might as well be called “Diet Coke” and “Diet Pepsi,” completely agree on, since each must have its spoonful of high-fructose corn syrup to help the other’s bitter medicine go down.

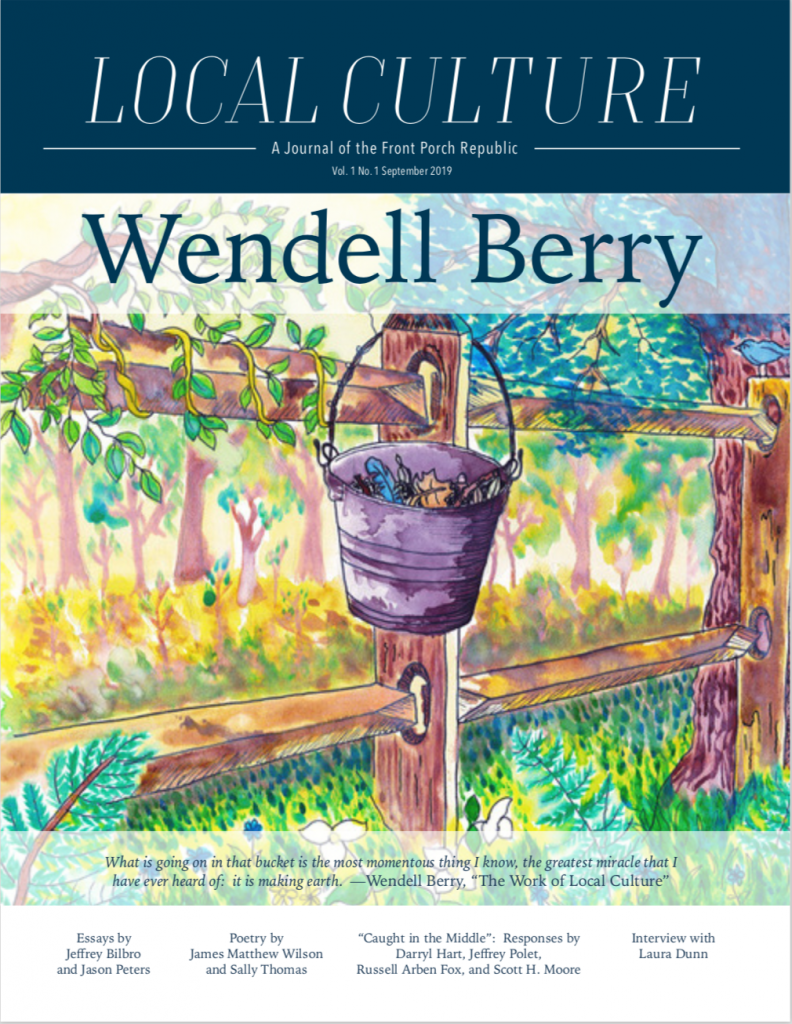

And so in 2019, at the tenth annual FPR conference marking FPR’s tin anniversary, we are pleased to bring out the first issue of Local Culture: A Journal of the Front Porch Republic.

It is no secret that from the beginning Wendell Berry has been a tutelary spirit of the FPR project. So just as the conference is devoted to his legacy, the first issue of the journal is a tribute to his importance in the ongoing quest for eudaimonia.

A single issue of a journal cannot consider the full range of Berry’s importance to American life and letters. The pressing concerns he has turned his mind to—kindly use in farming, forestry and mining; the defense of the small farmer and the rural place; the articulation of liberty and freedom as functions of competence at fundamental tasks; the ennobling of the domestic arts and the arts of making-do; abhorrence of war and war-faring tactics, whether military or economic; distrust of abstraction; respect for natural limits; submission to nature as both mother and judge; the necessity of goodness and kindness and forbearance, without which we are less than we can be; the hubris by which we would become more than we should be; the humor and mischief that season life; the poetry that adorns and lends it meaning; the sentence and solas of story-telling, that distinctly human practice without which we cannot know our places or ourselves or those around us—these and other pressing concerns that Berry has turned his mind to can be approximated only by Berry’s own considerable life and work. For it is fair to say that his life and work, like the seed-bearing fruit, is larger than itself. But then this is true of all that is good. It is true of goodness as such; it is a feature of earth’s increase.

So we hope the gesture here will suffice for the nonce.

Berry once wrote that he is willing to be part of a movement so long as it agrees to remain poor. Remaining poor is one thing FPR is especially good at. For ten years we have done whatever we’ve done pretty much gratis. We dream about having a shoestring budget. The project has been either a labor of love or a labor of lunacy, depending on whether you’re the one at the writing table at midnight or the flummoxed spouse leaning against the door jamb with Dr. Johnson’s doctrine—“no man but a blockhead ever wrote, except for money”—trembling like a compressed spring between your lips. But we have enjoyed the largesse of one sponsor in particular, John Tamming, who has quietly helped with several conferences and who has gently insisted that we get on with the job of bringing the project to the palpable page of the periodical. On behalf of everyone on The Porch, writers and readers alike, I offer my gratitude to John for underwriting this first issue of Local Culture and making it available to readers free of charge. (Hereafter readers will have the privilege of subscribing.)

I write these words shortly after the summer equinox in Ingham County, Michigan, specifically in Williamstown Township, more specifically still from the homeplace, where, in A.D. 2019, the garden thrives, the bees in the bee-loud glade make honey, the hens furnish forth the breakfast table, and where these and much else remind me not to hope for a better place but to be worthy of the one I’m in.

Prior to reading your introduction, I had ordered a subscription to Local Culture. Imagine my surprise when I read you’re from my home state! And I know where Williamston is. Years ago, I bought a picture of a hen laying on a nest, painted on linen with numerous hidden items in the work.

I no longer garden or live in the country, but my heart is there. Wendell Berry’s “The Unsettling of America” was my first introduction to his writing. His work keeps me grounded.

I look forward to many years of reading Local Culture.

Please forgive my punctuation mistakes, etc. I have diminished memory due to an intentional act.

Comments are closed.