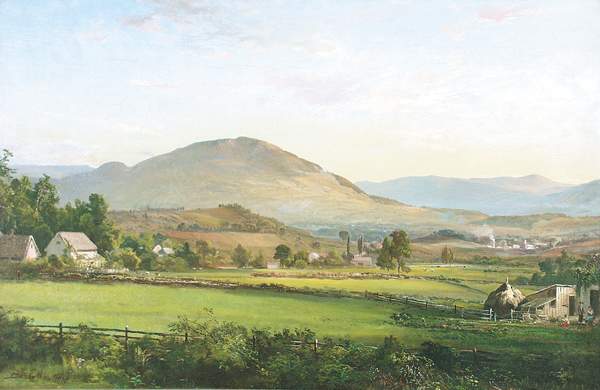

In Wordsworth’s great poem, “Lines Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey,” the speaker surveys a rural scene from a promontory. First time readers, especially those unfamiliar with the British countryside, might mistake this scene for a “natural” or “pristine” landscape:

…Once again Do I behold these steep and lofty cliffs, That on a wild secluded scene impress Thoughts of more deep seclusion; and connect The landscape with the quiet of the sky. The day is come when I again repose Here, under this dark sycamore, and view These plots of cottage-ground, these orchard-tufts, Which at this season, with their unripe fruits, Are clad in one green hue, and lose themselves 'Mid groves and copses. Once again I see These hedge-rows, hardly hedge-rows, little lines Of sportive wood run wild: these pastoral farms, Green to the very door; and wreaths of smoke Sent up, in silence, from among the trees! With some uncertain notice, as might seem Of vagrant dwellers in the houseless woods, Or of some Hermit's cave, where by his fire The Hermit sits alone.

Unspoiled? Yes. Untouched? No. This landscape has been shaped by human hands. Cottage ground, orchards, copses: all of these are managed, agricultural features of the land. So are the “hedge-rows, hardly hedge-rows, little lines / of sportive wood run wild.” As a teacher of British literature in an American college, I find that my students are mostly unable to imagine what the speaker is seeing here. This is not surprising, since to an American a “hedge” calls to mind a string of puny shrubs along the front of the house. A hedge “run wild” means some boxwoods that someone forgot to trim.

This is not what Wordsworth has in mind at all. A hedge is a livestock-proof barrier made of carefully “laid” woody plants: the trunks of the larger plants are partially cut through and then each is leaned over in the same direction and occasionally staked and tied. The result is a stock-proof barrier. The process must be repeated every few years; if neglected, a hedge will begin to grow vertically, and, eventually, the bottom will thin out because of lack of sunlight and become permeable to livestock. This is what the speaker is seeing from his promontory: the top of a neglected hedge that is growing into a line of woodland.

Hedges and the art of hedge-laying were born of a combination of necessity and a habit of harnessing nature’s energy in simple but ingenious ways (think watermills). In places where trees and shrubs were plentiful and stones were scarce—and centuries or millennia before the invention of wire fencing—hedges were the best way to create a strong fence. They requirement maintenance, yes, but they are also made of ever-renewing materials that want to be there. Depending on the area within Britain, hedges may be as large as ten feet tall, ten feet thick and composed of half a dozen or more native species. This mentality of working with and not against nature is what Wordsworth—already sensing the threat of the industrial revolution—is praising. The groves, copses, hedges, and even cottages, built of local materials and “green to the very door,” are tucked into their setting and scarcely noticeable.

Wendell Berry has pointed out that people today tend to think about a piece of land in only two ways: either as sacrosanct (usually because it is considered “scenic”) or as land that can be used—or abused—in whatever way will produce the most short-term profit. Berry argues that most land should fall into a third category: that of land that is used well, to its own long-term enrichment and also to the long-term benefit of its owners, caretakers, and neighboring communities. Berry is invoking the vision of Wordsworth: a landscape where people work the land in a way that harnesses and harmonizes with nature.

In praising this third way, I do not mean to criticize the recent trend of “rewilding.” For one thing, there is a place for truly wild land. For another, the rewilding projects I am familiar with include agricultural and other economic activities. In other words, “rewilding” at its best is not an overreaction against industrial agriculture, which destroys and excludes nature. It is does not exclude people or destroy livelihoods. The problem lies not with agriculture but with industrial agriculture. It is worth remembering that, as William of Normandy’s Domesday Book tells us, most of the land in England has been in use since pre-Norman times, yet an astonishing 97% of its meadows, bastions of dozens of plant and animal species, have been lost to grass monocultures, the plow, and development since the end of World War II. Hedges went the same way.

In post-war Britain, when tractors replaced oxen and plough horses, and intensive agriculture became the official goal, the Ministry of Agriculture subsidized the removal of hedges, many of which had been planted in the medieval period or earlier, to make more room for plowing and grazing. More than 300,000 miles (just over half) of Britain’s hedges were removed. It did not take long for the disaster to become apparent: wind and water erosion increased and numbers of beneficial insects and birds, who had depended on the hedges, collapsed.

It turns out that hedges are important wildlife habitat and serve as corridors allowing wildlife to move without having to break cover. In a rural landscape where intensive agricultural dominates, hedges may be the closest thing to wilderness. I often tell my composition students something that I first learned from Berry, that many of the problems our society seeks to mend were once considered “solutions” to some other “problem.” And this is why we so often find ourselves walking-back previous initiatives. The British government now subsidizes the replanting of hedges, and tending to them has become a revived art. One could easily become an armchair YouTube hedge-laying expert, learning traditional techniques particular to each region of the U.K.

What about America? In the southern plains, the place I know best, the swift settlement and relative lack of woody species on the open grasslands meant that there was much less of a tradition of planting hedges. (Bois d’arc hedges were planted for similar reasons to British hedges: to contain livestock and to create windbreaks. Though I have read about these hedges, I have never seen one, nor the remains of one.) After the destruction of the buffalo, livestock roamed in open range, and then, with the coming of barbed wire, vast spaces could be enclosed cheaply and quickly. Where I am from in Central Texas the plains were more like savannah than open grassland. A pattern of woods and grassland emerged from the contest of two forces: water and fire. Trees could grow more readily in low, relatively moist areas, while the higher, drier and more exposed areas were occasionally swept by wildfires, limiting the spread of trees and shrubs and rejuvenating grassland.

Since settlement by Europeans, the Texas landscape has changed in complex ways. And the history of these changes is controversial. While some lament the spread of woody species onto what is thought to have been grassland, others point out that the spread of “less desirable” species like Mountain Cedar (juniperus asheii) is nature’s way of healing overgrazing and other harmful ranching practices. In any case, there can be no doubt that both overgrazing and over-plowing have been and continue to be destructive forces.

I live on the line between the Blackland Prairies—rich, rolling farmland bisected by streams flanked by narrow, low-lying woodlands—to the east, and the Cross Timbers—a diverse blend of woods and grazing land—to the west. It doesn’t take an expert to see that nature is suffering in both of these regions. In the Blacklands, huge fields of hundreds—sometimes thousands—of acres are kept in continuous cultivation of monocultures, usually corn, wheat, or cotton. Even when they are allowed to rest, cover crops are often spurned so that vast areas of bare dirt are exposed for months on end. Some farmers do not plow on contour; others ignore small waterways or draws, or leave only a small fringe of grass around them. The results is erosion. Add to that the repeated application of synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides, and it is not hard to see why these places are dead. God’s country, in many cases, looks more like a hellish industrial waste: patches of bare dirt punctuated by yesterday’s rusted out mistakes. The non-arable grasslands of the Cross Timbers fare better but not by much. Here, decades of overstocking haves led to the loss of native grasses, exposed soil, and erosion. Many of the pastures look weedy, with low, poor-quality grass.

Is there anywhere in this desolation that nature reasserted herself? Yes. On the margins, in the fencerows, and alongside the backroads. I live in town on a forgotten acre that we stumbled across and built on. The acre is bounded by a derelict wire fence that, in places, has a foundation of limestone rocks and cement. The fence is probably at least 100 years old. In recent decades this fencerow had become grown over with invasive species such as ligustrum, chinaberry, and nandina. Now that I have cleared these, the fencerow is anything but clear: a blend of native trees and shrubs such as hackberry, western soapberry, cedar elm, pecan, various species of oak, Mexican buckeye, and elbow bush adorn the old fencerow. I planted some of these, but many more have planted themselves. They bring a touch of rural life to our neighborhood and offer a healthy level of privacy from our neighbors. More than that, they offer wildlife. Squirrels, lizards, tree frogs, and many kinds of birds live there, some even prefer the woodland-edge-like habitat to deep woodland cover.

In the country just outside of town, wire fences along the edges of pastures or ploughed fields are grown up with trees and shrubs. Many of these rows have been removed to make way for more ploughland and to accommodate bigger machinery. But where they remain, the most common trees along Central Texas fencerows are hackberry and cedar elm, along with a few oaks and pecans. In one way, this is a surprising combination: hackberry is a fast-growing pioneer species labeled by many landowners as a “trash tree,” while cedar elm is a slower growing, “desirable” climax canopy species. But the story can be reconstructed: hackberry is an important source of food for birds. They digest the thin, tough-ish flesh (which tastes faintly of red-hots) and pass the rock-hard seed when they take off from the fence. Hackberries grow fast and plentiful. So, it makes sense that fencerows grow up in hackberries. Once hackberries get established they catch blowing cedar elm seeds, and they also provide cover in which slower growers like cedar elm can thrive. As the trees mature, they provide habitat for squirrels (and blue jays) who bury acorns and pecans there. After a few decades, a diverse, linear woodland comes into being. A couple weeks ago, I walked along maybe a quarter-mile of fencerow. On one side all of the vegetation has recently been cleared. On the other a ten-foot wide strip that is maybe fifty years old persists. As I walked a made a mental list of the species I saw: cedar elm, mountain cedar, live oak, Texas ash, Texas persimmon, Mexican plum, possumhaw holly, gum bumelia, wafer ash, Eve’s necklace, and a few others. (Emerald ash borer has made it to Central Texas, so the Texas ash will not last long. The wafer ash, not a true ash, is safe.)

In other words, if you’d like to have an old fencerow of your own, you don’t have to work very hard. You just have to resist the temptation to fight nature. (If you do intervene, you can intervene on nature’s side and speed up the process by planting appropriate trees and shrubs and pulling exotic invasive species). Fighting is a lot harder and less rewarding. About fifteen years ago, a family member spent a very hot, miserable summer cleaning several hundred yards of fencerow on the family farm in East Texas, where the trees grow so fast it’s surprising you can’t hear them doing it. Today, you can barely see evidence of that misery. Hundreds of small trees have grown back, either from seed or from where they were cut. The result is not unpleasant. As you walk the little blacktop road, you can still see through them into the pasture, yet you also have shade and birdsong close by. When you’re in the pasture, you have a better sense of its boundaries than you would if the fence were clear. An uncle of mine on another property nearby has wised up. Not only does he not attempt to keep trees and shrubs out of fencerows, he repairs the fences using living trees as posts, as neat and thrifty a method of fence repair as I can think of. Granted, in some places and with some kinds of trees, it might prove too hard to repair a fence in a grown-up line, but the larger and thicker the line becomes, the less undergrowth there is, and the easier it becomes to move through with wire and wire stretchers.

I have heard people praise “clean” fencerows, and I, too, have felt distaste for what I deemed “untidy” or “neglectful” stewardship. And surely all of us have driven along miles of grown-up fencerows without giving them a thought, or even noticing them. But I think it is time that old fencerows gain our attention and our appreciation. They are our “hedge-rows, hardly hedge-rows, little lines / of sportive wood run wild.” They are places where tooth and claw cling tooth-and-nail to life. We can work toward a future where better farming and ranching (and gardening) practices lead to greater harmony with native plants and with wildlife. And in the meantime, we can look at the old fencerow, and we can wish it well. We can praise the old fencerow for its wildness, but also for its homeliness. It reminds us that man and nature need not always be at odds.

What about the majority of us, who don’t farm and don’t live in the country? Can we have an old fencerow, or (for the Anglophiles among us) a hedgerow? If you have a fence or a boundary, however tame, however suburban, the answer is yes. Measure a six to ten-foot strip along a boundary and plant it with half a dozen or more native species of trees (canopy and understorey) and shrubs. Plant a mix of deciduous and evergreen species (so that birds have some winter cover). Plant them densely (anywhere from two to four feet apart), and plant them randomly. Under them, scratch in native shade-tolerant grass and wildflower seeds. As the trees and shrubs grow in fill in during the first few years, you’ll do little. After that you can begin making decisions about how your fencerow will grow. You could prune everything to remain short, well below any existing canopy trees. Or you could allow a few trees to grow taller while keeping everything else low. Heavy summer pruning discourages growth, while light summer pruning encourages thick, shrubby regrowth. Winter pruning, especially hard pruning, encourages regrowth. Don’t worry about planting large species of trees. If one begins to get too big you can—provided it isn’t a conifer—coppice it: cut it back at or just above the ground in mid-winter, and allow it to grow back as a multi-trunked tree.

Within five years you could have a tiny piece of managed nature, in which more birds sing than you would have thought possible, where the soil itself has been enriched by the life growing out of it and living above it. And where you yourself find a way not just to connect with nature, but to live with it, and to use your uniquely human gifts to tend it and help it grow. You might even get some firewood out of the deal.

Image Via: GetArchive

You have redeemed hackberries for me, sir.