Words beyond words.

I was part of a lively discussion with some of the Brothers of our Fellowship about words and learning to read and analyze them. We were prompted in this undertaking by a quote from T. S. Eliot: “While the practice of poetry need not in itself confer wisdom or accumulate knowledge, it ought at least to train the mind in one habit of universal value: that of analysing the meanings of words: of those that one employs oneself, as well as the words of others” (The Idea of A Christian Society).

Since we had been working through some of the poems of Malcom Guite in previous sessions, I thought comparing Emily Dickinson’s “How happy is the little stone” with Robert Frost’s “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” might be a good way to probe Eliot’s point.

The exercise resulted in more than I had hoped.

The Brothers immediately identified similarities between the poems—iambic tetrameter, a discernible rhyme scheme, a focus on some aspect of creation—as well as their differences—a whimsical mood in Dickinson’s frolic as opposed to a more pensive one in the Frost, one stanza as compared to four, Dickinson’s use of images and personification contrasting to Frost’s merely descriptive narrative. All good efforts at analyzing and comparing the words of these poems.

The one observation on which all the Brothers focused with most interest, though, was what I might describe as the words beyond words. These poems are not just about a stone in the road and snow falling on a dark evening. The poets were both pointing beyond the items and situations the poems described to mysteries more affective than rational, spiritual than physical, and transcendent than immanent.

We delighted together over how observing a stone in the road or snow gently falling into a dark wood can launch us intellectually and, to an extent, experientially into another realm of existence. Neither Dickinson nor Frost boasted a profession of faith in Jesus Christ, yet they were both deeply spiritual and, in much of their verse, never very far from parting the veil that allows a glimpse into eternal verities.

Eliot’s observation proved true; but the works of Dickinson and Frost created an even more compelling lesson about analyzing and discerning the meaning of the words embedded in everyday things.

The very next day, reading an interview with Adam Plunkett in The Paris Review, I was pleasantly stunned by this comment on the poetry of Robert Frost, “As for the poetry part, I’d say that, for me, the biggest gift of the art is his ability to see potentially transcendent beauty and a sense of meaning in things that you’d otherwise think of as too obvious to really regard. It’s a kind of grace of attention.”

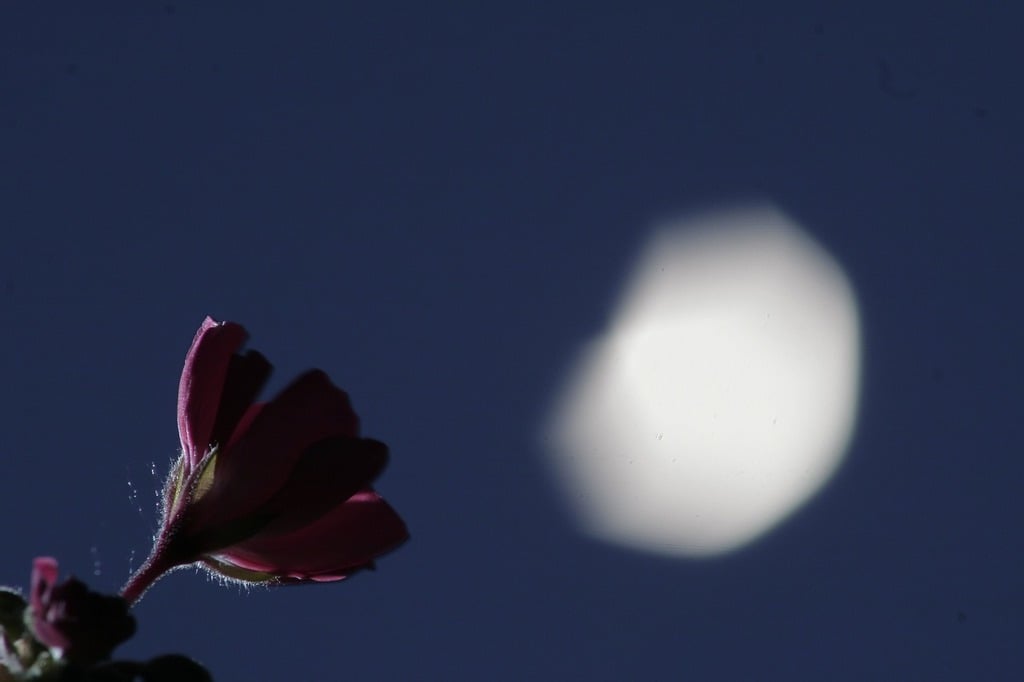

Obvious things; a grace of attention; transcendent beauty and meaning. Lovely, dark, and deep. The heavens and all creation declare the glory of God. No words are spoken, but powerful meanings are implied. All creation, not just a dramatic sunset, a towering cumulus cloud, a majestic double rainbow, or the expanse and brilliance of the night sky.

Hundreds of thousands of people from out of state made their way here to Vermont on April 8, 2024, to observe the total eclipse of the sun. A brief documentary was prepared by Vermont Public (PBS). The most beautiful part of the documentary was not the total eclipse but the response of the people. They danced. They laughed and cried at once. They hugged and held on tight. People were agog. They pointed excitedly or clapped their hands to their slack-jawed faces. Couples renewed their love for one another. And all these scenes were repeated in scores of places along the path of that heavenly event.

By the comments of many, the eclipse had been a transcendent experience—lovely, dark, and so deep they could not completely fathom what they’d seen. They had a few words, like “Oh my!” or “Wow!”—but those interviewed struggled to express their feelings. The extended frisson of the event had made an unforgettable impact on them, without voice or words, as David says in Psalm 19.

Those who observed the eclipse of 2024 would need no persuading that Dickinson and Frost were on to something. They had experienced transcendence in the eclipse. Such large experiences can train the soul for more careful “attention.” For as these poets attest, such experiences are not reserved only for big displays.

A stone is not the sun. And falling snow cannot compare with a full corona. Yet beauty and even glory can be found in each. Each bears words not spoken which yet beckon to be heard and understood.

All creation—humble or magnificent, temporary or more permanent—can teach us about the beauty, goodness, wisdom, power, and love of God. But more than that, creation can draw us into that love, into the orbit of divine pleasure. For God pleasures in everything He has made, and if, in our wanderings, rambles, or routine duties, we can practice the “grace of attention,” we may find Him reaching out to us, from even the most humble and quotidian things, with a word to be analyzed and a meaning in which to delight.

Developing the grace of attention requires, in my experience, two commitments: Think near. Aim small.

Since God is always speaking to us through the works of creation and even, because of the mystery of His common grace, through aspects of culture, some entrance to His pleasure awaits us at every moment. But don’t strain to see too high or too far. Think near. Look to the people around you. The furnishings of your study. The plant basking in the sunlight on your sill. The books in your library. The dog asleep at your feet. The tools of your trade. Think like Dickinson or Frost, so that you pause to contemplate the Source of these good and perfect gifts and wonder about what they can teach us of Him. Esteem them for their shape and the words they suggest. Thank God as you analyze an item—shape, color, use, reliability, texture—and for the transcendent meaning it suggests. Take your time. For all these gifts of God are lovely in their own way, and they can draw you into depths of meaning and divine pleasure if you will practice the grace of attention.

Then, second: Aim small. That is, relish the moment—like Lewis and joy—before it is suddenly gone. Don’t expect an ecliptic “Wow!” Delight in the glimpse. Revel in the passing sound. Enjoy the momentary transposition into that pleasure which one day we will know without interruption and forever. Though even then, while the darkness of divine unknowing brightens in the light of the glory of God, the deep things of God will continue to be a source of eternal mystery and delight.

Analyze God’s words in creation and ponder their meaning. But don’t look for big lessons or profound teachings. Embrace small things. Bigger insights may come over time, especially if you journal your experience, or write a poem, such as this one I composed, having stumbled upon a new (for me) wildflower under the maple tree in the circle of our cul-de-sac:

The clear night sky spreads wide a tapestry

of beauty in the stars that shimmer all

throughout the cosmic exhibition hall.

In every age mankind has looked to see

and wonder at the might and mystery

to be discovered there. Wrapped in the thrall

of such majestic beauty, we feel small,

while our thoughts contemplate divinity.

Not all stars occupy the heavens, though.

In sandy, semi-shaded places, right

beneath our feet, bright stars of reddish pink,

a small sun shimmering from their center, wink

and wave and call out to insist, the night

sky's beauty matches well with things below.

Reading this, analyzing my own words by which I tried to bear witness to that first encounter with Centaury, and the meaning that encounter has had for me, I experience the pleasure of God all over again.

Lovely, dark, and deep. Think near. Aim small. Know the grace of God through the attention you invest in His words coming to you from the lovely world right around you. And sometimes, right under your feet. Worlds of wonder await us in “things that you’d otherwise think of as too obvious to really regard.”

Image via PxHere