Judging by the title, readers would be forgiven for thinking of The Black Intellectual Tradition: Reading Freedom in Classical Literature as a survey of critical individuals in the American black intellectual tradition. But this is not what the book is fundamentally. Rather, authors Angel Adams Parham and Anika Prather present a witness, an example, and apologetic for the unity of humanity around goodness, truth, and beauty. The book provides an apologetic for classical educators to deeply investigate and study the great intellectual and rich tradition of black intellectuals over the past four hundred years.

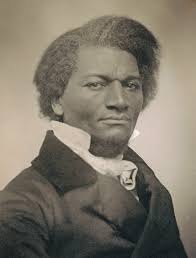

It also illustrates the great impact classical education had upon black thinkers such as Phillis Wheatley, Frederick Douglass, Martin Luther King Jr., and Anna Julia Cooper, and how it still ought to be embraced by communities who are commonly without access to classical education. Thus, it is a case for those already immersed in classical education and its tradition to further expand their knowledge and praxis by becoming conversant with American black intellectual tradition, as well as an appeal to American black culture to recognize the blessings classical education has given to all peoples who have joined to it. The authors endeavor to balance the proper relationship between the uniqueness of individual experience alongside the universality of human experience. As such, they highlight the giving relationship between one generation and another through the continuing gift of education rooted in the wisdom of the past while increasing its wisdom with every passing generation.

The book is divided into two parts. Part 1 examines the black intellectual tradition under the lens of the true, good, and beautiful. The true looks at the difficult past that lays behind the tradition. The good explores learning from Martin Luther King Jr. and Anna Julia Cooper. And beauty follows the poetic mind of Toni Morrison. Part 2 takes up Anna Julia Cooper again from the perspectives of truth, goodness, and beauty. The whole work is thus crafted to consciously do the work a classically educated mind would do while showing how the black intellectual tradition is filled with the good, true, and beautiful.

As for the specific content of the book, there are individual conclusions and assertions which the reader can diverge from or protest, yet the general thrust of this book is both a step in the right direction for these discussions while also highlighting important figures enough to spark a desire for greater inquiry. Its greatest weakness is the breadth of figures and themes it surveys without having the opportunity to explore them further. Still, they cover the people and themes well enough to convey their thoughts while also inspiring the reader to read the sources for themselves.

Space precludes fuller treatment of some investigations, and the authors helpfully provide detailed footnotes as a starting point for greater inquiry. I think certain examinations require more nuance. For example, the reference to legal Black Codes in such places as Louisiana are plain in history and easy to demonstrate as attempts to perpetuate prejudiced policies against black Americans. This ought to be lamented and remain in the historical record as dark reminders of legality waged against a particular group of people. However, it is an overstatement to suggest American policing in totality is descended from southern slave hunter policies (69-70).

Even a cursory look shows that much of the essential founding of the core of American policing was an adoption from the British father of modern policing Sir Robert Peel, and his concepts were created many years after slavery was abolished from Britain. In addition to this, each state, and sometimes even counties and cities developed different policies for policing, among which include such things as Black Codes in some southern states, but such was not the basis of policing in states like California or later ones in the Mountain West.

The authors at times briefly engage with African concepts and their potential residual preservation in Black American culture, but alas, these are brief and not explored in detail as one might want such as oral tradition (20-21), drumming (23), iconography (23), conjuring (122), and others.

Oral tradition in particular left me wanting a deeper exploration, as they rightly highlight the universality and ancient pedigree oral tradition possesses and with it, a differentiation from written words. Principally, oral tradition is important and powerful, but their use of Socrates without further qualification caused me unease. As they quote him: “when they have been once written down … are tumbled about anywhere among those who may or may not understand them, and know not to whom they should reply, to whom not: and, if they are maltreated or abused, they have no parent to protect them; and they cannot protect or defend themselves.”

This section could have been a great opportunity to reinforce their point about the educator’s role by emphasizing that oral teaching and reading go together. However, their emphasis was on the loss of African traditions because they were not written down, and they clearly make much about the importance of literary texts throughout the rest of the book. They ably highlight the destruction of generational memory with the Atlantic Slave Trade elsewhere, and so revere the written word, that I think they could have honored the glory and beauty of oral tradition without risking a mistaken denigration of the written word. I do not believe it was their intention, but perhaps a later edition of this book, or similar thoughts could rather convey the importance of oral explanation joined with literary understanding.

Some readers might be suspicious of the use of terms like “privilege,” “power,” or “oppression,” given the ways in which some use those terms from a purely postmodernist and ‘critical’ sense where one weaponizes those terms to overthrow another class. Those are understandable reflexes. However, reading the entire book from cover to cover, I do not think that is what the authors intended; rather, they are often highlighting in the historical progression of the American black intellectual tradition the great impact of slavery and oppression had upon everyone in America and its trajectory. Precisely here is where I think the authors excel, for while they rightly contend for liberty and equal opportunity, they highlight how powerful the classical Christian tradition was in giving true liberty to black Americans.

As they quote James Baldwin:

You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was [books that] taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, or who have ever been alive (4).

Similarly, they highlight how Frederick Douglass was inspired to learn to read when he inadvertently heard from his master that such knowledge would make Douglass “forever unfit to be a slave” (64).

And speaking of Douglass, one element they centrally highlight about his example and contribution to us is how he runs so contrary to the general disposition of some today who either see injustice in every word or disregard all claims of prejudice. As one greatly impacted by the writings of Douglass, I concur with the authors when they state: “With this delicate balance, Douglass accomplishes what so few seem to be able to accomplish today in our racially polarized times: he acknowledges what is praiseworthy while also taking time to lament the heartache, pain, and suffering of his people” (67).

W. E. B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington are rightfully given some examination by the authors, with an acknowledgement of the different avenues they took toward enriching emancipated black Americans after the Civil War, with Washington’s emphasis on trade work and productive life skills through the Tuskegee University and his Atlanta Compromise versus Du Bois’ emphasis on classical education. It is difficult to capture the nuanced debate between these two schools of thought with such limited space, although the authors feel the Department of Education effectively exploited the Compromise to be the primary way of seeing black Americans educated with a constant attack coming against classical education in the black community (156-158).

Whether this is true or not, I think some of Washington’s genius is not entirely revealed under this premise. For an alternative thought on the long-term vision and virtues of Washington’s method, I recommend Thomas Sowell’s many discussions of generational wealth and status as can be found in a few of his essays in White Liberals, Black Rednecks. In brief summary, one or two generations investing themselves in marketable skills and business enterprises eventually accumulate enough wealth and status, that even if they are despised by the broader culture, they provide the means for the third and four generation to acquire elite educations and the opportunities that accompany it. Intriguingly, the authors do not spend as much time on the conflict between Du Bois and Washington rather focus much more of their attention on a mediating position found in Anna Julia Cooper.

Although there are dozens of other significant figures highlighted through the text, Anna Julia Cooper and Toni Morrison take up the lion’s share of the authors’ ink. Morrison highlights the beauty side of the classical triad. The authors explore her poetic and sacramental imagination, particularly through her novel Song of Solomon where she “weaves together African American history, culture, and folklore with classical and biblical themes and stories” (134). The story embodies the experience of many black Americans descended from slavery longing for history, family, purpose, and a true sense of justice.

One of the central reflections they derive from the novel is beautifully summarized as follows—“We can infer from this that though we all long for justice, the kind we wrest for ourselves, without mercy, may carry a cost too high to bear. Our judgment is nothing like that of the master of the vineyard whose punishments and rewards can seem inscrutable but are ultimately merciful and just” (133). The struggles of the central characters are herculean, yet they result in finding their history and their place in the world, a motif that can be shared with many throughout the world longing to know their heritage and above all, their Creator and his family, his justice and his mercy.

Anna Julia Cooper, alongside Martin Luther King Jr., highlights the good of the classical triad in part 1, but in part 2 she is the prime example given for embodying all three of the triad. Her mediating position between Du Bois and Washington comes from her educational journey, where she learned industry, trade, and hard work through the Ladies’ Course at St. Augustine before being permitted entrance into the Gentleman’s Course where she learned Latin, Greek, and the classics. They emphasize that she believed the trades had been taught for centuries to Black Americans, but they had often been robbed of the opportunity to stimulate their minds and receive a classical education (159). She believed the training of the hands, heart, and mind were all essential for a well-rounded, whole body experience as a human being (159-166).

The last half of the book is devoted to her as an example of a black woman embodying not only the knowledge that is cultivated by a classical education, but the virtues and practical outworking of that knowledge. We see in her a special love for people that gives her immense patience with those struggling to find their way and a special sensitivity for providing a well-rounded education to anyone. Three of the last appendices are essays by Cooper, and her essay “On Education” is exceptionally thought-provoking, especially given its admiration for physical, mental, and spiritual education as a cohesive whole. Those who enjoy thinkers who are organic and unifying in their perspectives, Cooper’s essay will be delighted. Overall, one of the greatest strengths of his book is the reflection it gives to Cooper as an example par excellence of the black intellectual tradition. As they note concerning her, “She was willing to step outside of her own narrative, perspective, and life experience in order to use all that God had given to her to touch all of humanity” (190).

Different readers may demur at certain points made by Parham and Prather, yet the central thrust of their work is a step in the right direction for further enriching classical education while seeking to give an appeal for its merit among those who doubt its worth. It is a work that helps highlight our individual experiences and our universal connection go hand in hand. The black intellectual tradition has much to contribute to the ongoing gift of classical education.

The appreciation for and recognition of the need to include the American black intellectual tradition, is perhaps best summed up by Carl Trueman in his book Strange New World, where he writes:

To be sure, these ‘canon wars’ are not without merit. As a historian, I welcome the advent of approaches to history that bring attention to marginalized voices. Marxists such as E. P. Thompson made significant contributions by highlighting the role of the working class. African American history has done sterling service in pointing out that the history of the United States cannot be told simply from the perspective of white males, with everyone else playing little more than bit parts. Slavery shaped–and its legacy continues to shape–the experience of African American in the United States. The voices of people of color are a vital part of the American story, both for offering perspectives on the dark side of American history as well as enriching discussion of one of the key motifs of the American experiment: the ideal of freedom and how it has, or has not, been consistently realized in American culture. And all historians should welcome challenges to their own viewpoints and interpretations. That is how we grow in our knowledge of the past and of what it means to be human. The expansion of the canon to include the previously disposed and ignored can only enrich the historical discipline, as it can other disciplines such as literature and music (164-165).

Different context and different eras of classical education will likely warrant specific selection of what works to present to students in a classical education. The “canon” may one day be quite expansive if Christ’s return tarries for a few thousand years, yet the limitation of time and prudence will require parents, educators, schools, and scholars to select specific works within that broader canon. Much will likely revolve around the historical progression of what has led to the specific student’s era and cultural context (with an admonition that sources of the past also have definitive wisdom to speak to living generation), yet one should not neglect what an “outside” perspective brings to the table. Surely, in an American context, it will ever remain prudent to encourage students to read Frederick Douglass, Du Bois, and others, yet that doesn’t mean such authors do not have rich gifts to share with students of a Japanese household living in South Korea, or that a suburban home in Indianapolis has nothing to learn from Chinua Achebe or Sadhu Sundar Singh.

As the Dutch theologian Herman Bavinck noted, “We are all, whether we will or not, standing on the shoulders of former generations” (199-200). Yet as men like Du Bois and Douglass pointed out, their generational heritage was stolen from them, but they gained an ancient family through their studies of the classics (141). Parham and Prather’s work reminds us that the Christian faith and its preservation of the classical heritage of the world welcomes any who would come to receive the true source of goodness, truth, and beauty—the Triune God, and with him, a family made up of embodied people with their own unique experiences, yet all the one body that is Christ. For those given the gift to acquire a classical education, may they receive the many gifts the black intellectual tradition has to offer, alongside the other intellectual traditions within the stream, and in so doing, share these gifts with others.

Image Via: Wikimedia Commons